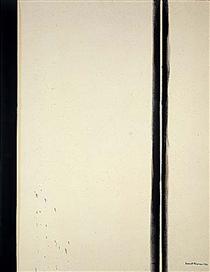

Antique Polish Cane, photo by Ellen Hinsey

“On the other hand, Polish society—under cultural pressure from the ‘rotten West’ (as Putin puts it)—is rapidly becoming increasingly tolerant. In short: the Church is losing the battle to Netflix.”

Polish poet, novelist, prose writer, and visual artist Jacek Dehnel discusses his life growing up during the Solidarity Movement in Poland, the effects of the Polish Catholic Church on politics and freedoms in Poland, and contemporary conflicts in Eastern Europe. We are honored to present two of his poems, “Tenebrae Responsoria” and “An Image from Afar,” both translated from the Polish by Karen Kovacik, and an interview between Dehnel and NER international correspondent Ellen Hinsey.

Two Poems (“Tenebrae Responsoria” and “An Image from Afar”)

Interview: Polish Memory, Poetry, and the End of the Swans

This is the fourth in our “Literature and Democracy” series. This quarterly column, curated by NER international correspondent Ellen Hinsey, presents writers’ responses to the threats to democracy around the world, beginning with a focus on Eastern Europe.