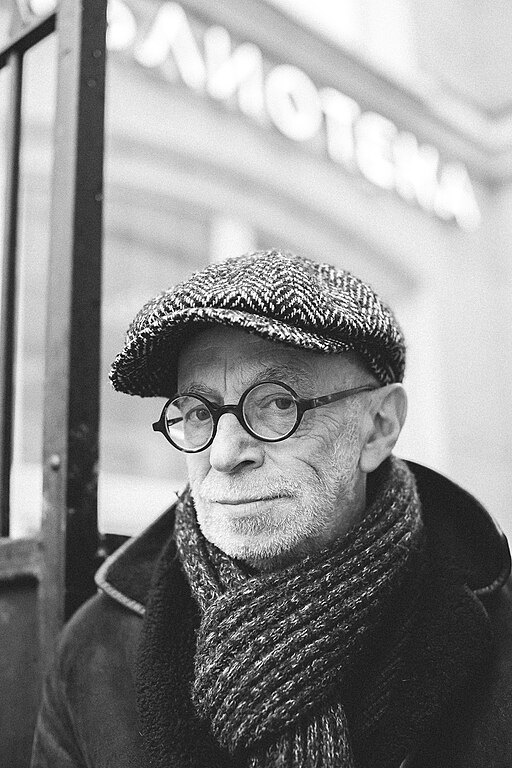

Lev Rubinstein

“Apoliticism is one of the most widespread types of conformism today . . .”

Writing Poetry After Kolyma: An Homage to Lev Rubinstein

This is the eighth in our “Literature and Democracy” series. This quarterly column, curated by NER international correspondent Ellen Hinsey, presents writers’ responses to the threats to democracy around the world, beginning with a focus on Eastern Europe.