Embrace the warm weather with eight hot new titles by New England Review contributors.

FEBRUARY & MARCH 2024

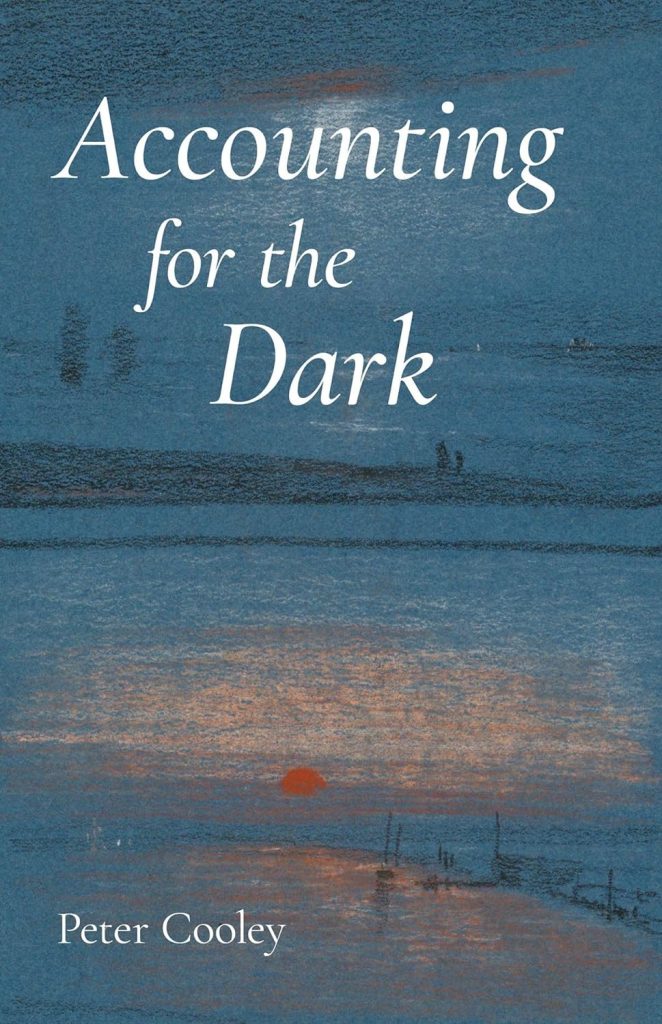

Peter Cooley, Accounting for the Dark (Carnegie Mellon University Press) — published most recently in NER 35.2

” . . . a luminous collection that will leave even jaded readers reawakened to the beauty of perishing things and the mysteries of the unseen.”

—Julie Caine, Louisiana Poet Laureate 2011–2013

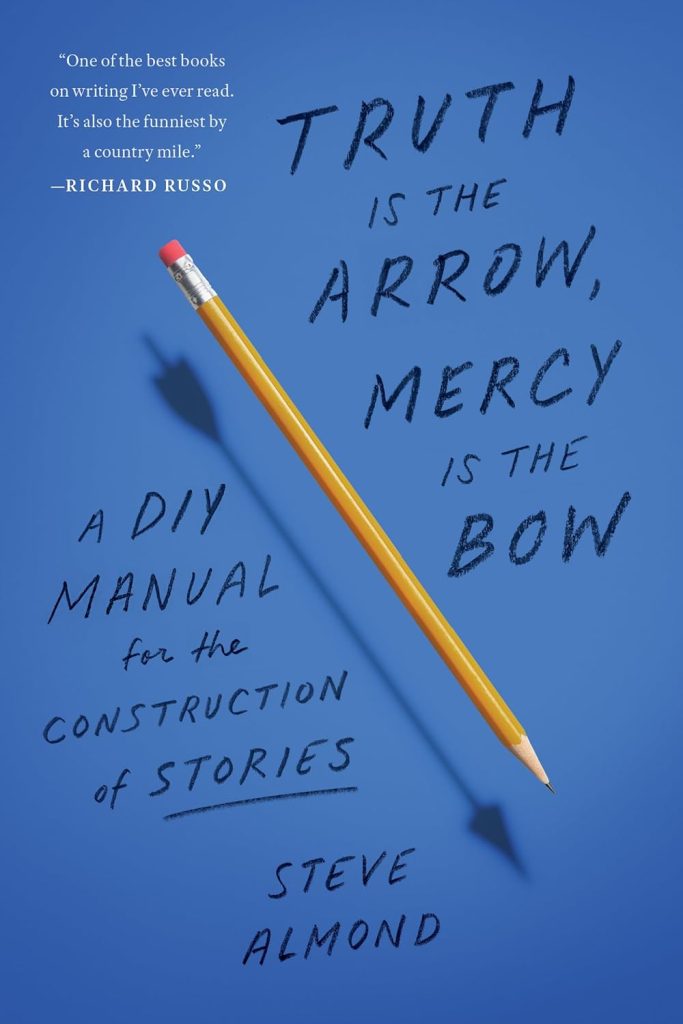

Steve Almond, Truth Is the Arrow, Mercy Is the Bow (Zando) — published most recently in NER 40.2

“Always candid and humane, Almond’s book will appeal to writers of all different skill levels seeking insights into the wondrous art of storytelling. . . .” —Kirkus

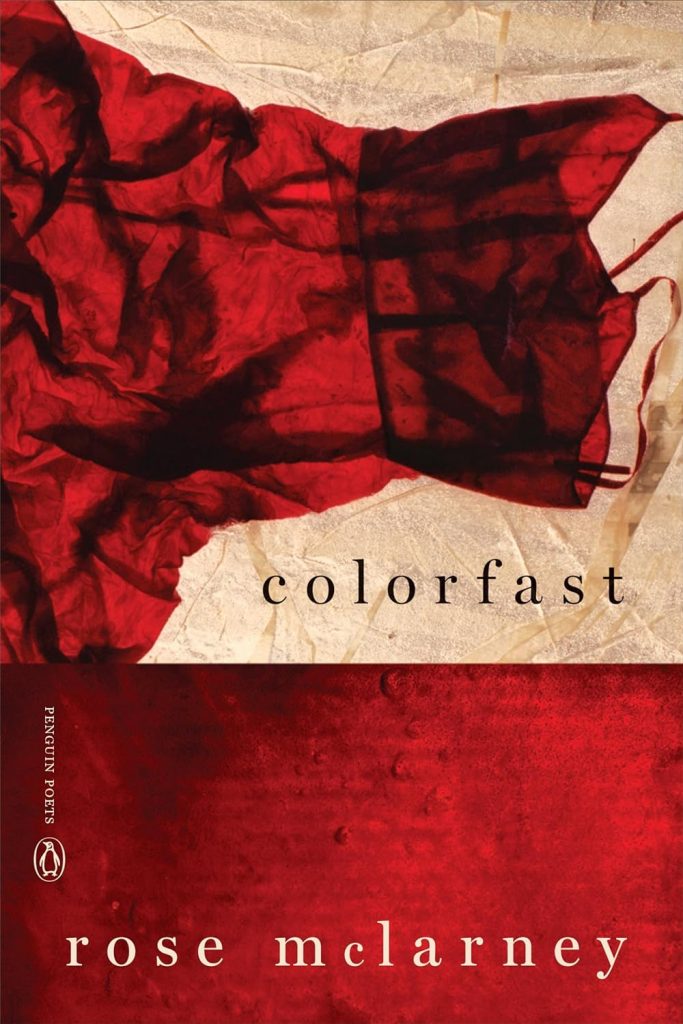

Rose McLarney, Colorfast (Penguin) — published in NER 32.2 & 40.1

“Colorfast is an exquisite book. Rose McLarney looks into the hard surfaces of southern Appalachia with a scrutiny at once ferocious and patient.”

—Joanna Klink, author of The Nightfields

Jessica Jacobs, unalone (Four Way Books) — published in NER 39.1

“Jessica Jacobs plays the Bible like a klezmer. She’s serious. She’s whimsical. She’s sorrowful. She’s kind. She’s measured.” —Spencer Reese, author of Acts

Kevin Prufer, Sleepaway (Acre Books) — published in NER 36.1 & 42.2

“In a poet’s voice, here aches the bittersweet awareness of how few moments we have alive. Here glows how we choose to love in the moments we have left.”

—Brenda Peynado, author of The Rock Eaters

Michael Krüger translated by Karen Leeder, In a Cabin, in the Woods (Seagull Books) — published in NER 37.3

“With attention and humility, respect and poetic mastery, with sadness and joie de vivre, humor and tragic resignation at the same time. The text draws you into the lyric cosmos of Michael Krüger . . .”

—Münchner Merkur

Diane Seuss, Modern Poetry (Graywolf) — published in NER 36.4

“Here at the bedside of this dying world, Diane Seuss is one of the exemplars of our modern poetry, and Modern Poetry is a resounding, enduring and yes, beautiful companion.” —Chicago Review of Books

Marianne Boruch, Sing by the Burying Ground (Northwestern UP) — published most recently in NER 45.1

“Ruminating about the pandemic, she asks, ‘Is there a case to be made for poetry in this plague year?’ According to these elegant essays, the answer is yes.”

—Kirkus Reviews