Ian Ganassi’s new translation of the Aeneid, Book 7, appears in the current issue of NER (37.2), and editor Carolyn Kuebler caught up with him recently to talk about his project of translating the great Latin epic. Ian’s translations of books 1–6 of the Aeneid have appeared previously in NER, and his poems have appeared in New American Writing, Yale Review, and other journals. His poetry collection Mean Numbers is forthcoming from China Grove Press later in 2016.

Ian Ganassi’s new translation of the Aeneid, Book 7, appears in the current issue of NER (37.2), and editor Carolyn Kuebler caught up with him recently to talk about his project of translating the great Latin epic. Ian’s translations of books 1–6 of the Aeneid have appeared previously in NER, and his poems have appeared in New American Writing, Yale Review, and other journals. His poetry collection Mean Numbers is forthcoming from China Grove Press later in 2016.

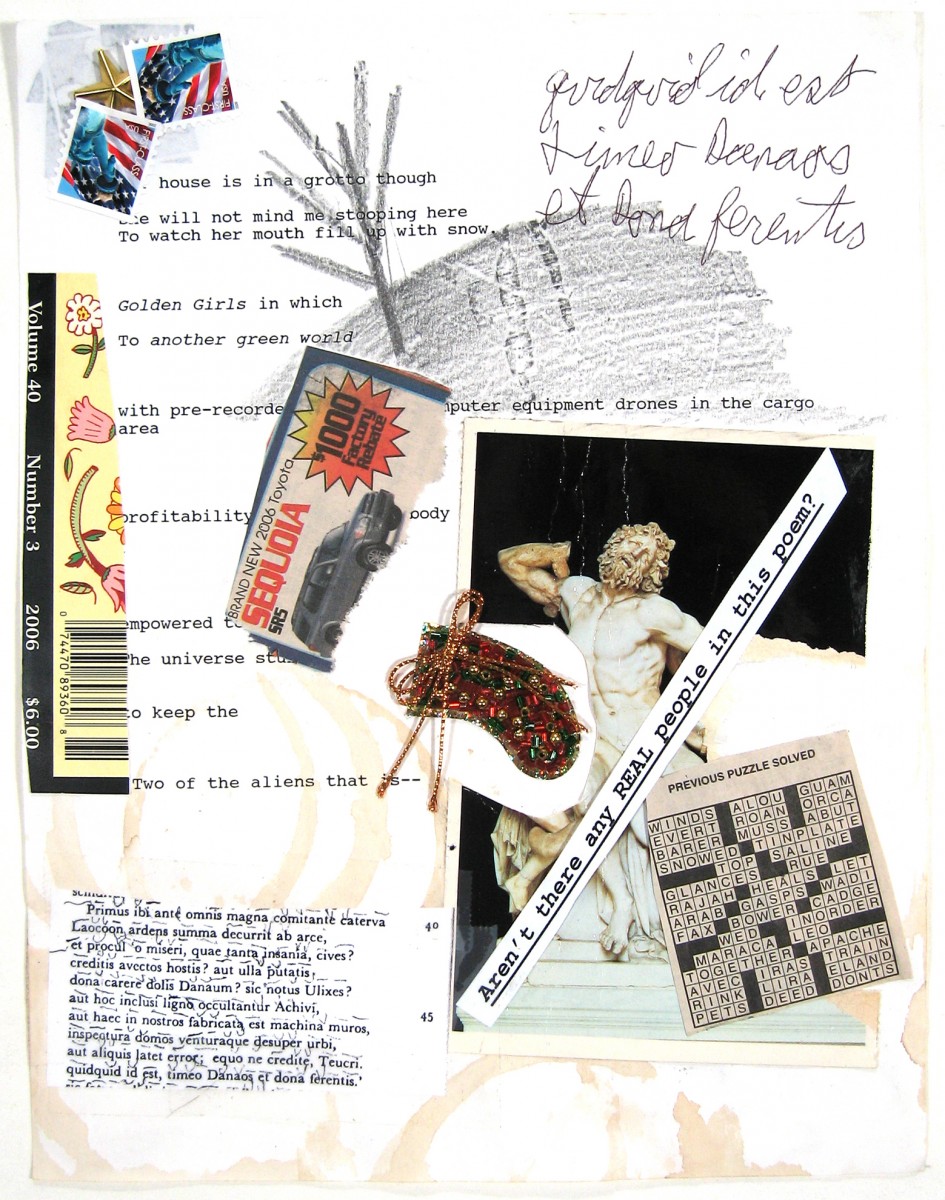

In addition to writing and translating, Ian also collaborates with painter Laura Bell on a series of collages they call “The Corpses,” which they have been working on since 2005. We’ve included two here: “Grandma’s Ancient Wine” (below) is a cut-up that Laura made based on a page of Ian’s rough draft of one of the books of the Aeneid. “Real People” (at left) takes off from the Laocoön story from Book 2. Just click the images to see them in detail.

CK: You mentioned that your fascination with antiquity dates back to childhood, to the stories of the gods and heroes, and that your unconventional undergraduate program led you to studying Latin. Why did you decide to translate the Aeneid, which strikes me as a particularly ambitious (and not exactly lucrative) undertaking?

IG: Translating, at least for me, is the best possible way to read the poem. I know the books I’ve translated much better than I would had I simply read them in translation. Also, since I write mostly lyric poetry, the translation is an enjoyable way to be involved in narrative.

I find Virgil particularly interesting because in many ways he is more like an author in the modern sense than Homer is, for instance. The Aeneid is original to Virgil in a way that more traditional epic can’t be to its authors/compilers. In that sense, the Aeneid is the first literary epic. Its frame of reference is vast, and the writing is beautiful, both of which attest to Virgil’s genius. He makes much of the traditional material he uses his own, either by the power of his poetry and/or by changing, and improvising with, the many stories and characters that are his source material. He also introduces stories and characters that are his own creations.

The poem has an almost novelistic feel, in that it works on several different levels of discourse. It is a political act—a study of the relationship of individuals to society and a consciously created myth of the origins of the Roman Empire. But it is also a study in individual human psychology and emotion. Aeneas is an exceptional man called to a divine mission. A constant tension in the poem is the extent to which a human being can transcend the weaknesses of his or her constitution in order to fulfill a role that approaches being super-human. As a man (or strictly speaking, as a hero, since his mother is a Goddess) and as a warrior Aeneas is constantly torn between his duty to the gods—his role as the creator of a new Troy—versus the complications and weaknesses of his own humanity and his personal psychology.

The poem has an almost novelistic feel, in that it works on several different levels of discourse. It is a political act—a study of the relationship of individuals to society and a consciously created myth of the origins of the Roman Empire. But it is also a study in individual human psychology and emotion. Aeneas is an exceptional man called to a divine mission. A constant tension in the poem is the extent to which a human being can transcend the weaknesses of his or her constitution in order to fulfill a role that approaches being super-human. As a man (or strictly speaking, as a hero, since his mother is a Goddess) and as a warrior Aeneas is constantly torn between his duty to the gods—his role as the creator of a new Troy—versus the complications and weaknesses of his own humanity and his personal psychology.

I feel I should also say that I am a very slow reader of Latin. It doesn’t come easily to me; I can’t “sight read” it, for instance. But I feel that the fact that I have to work hard to get the Latin right also helps me to get to know the text more intimately.

CK: It seems to me that Latin doesn’t have much place outside of educational institutions, and yet you’re not a professor or scholar of Latin. How did you go about learning the language, and then continue to pursue it outside of the university setting?

IG: I studied Latin for two years in high school and enjoyed it, so when it came to fulfilling a language requirement in college, Latin seemed a natural choice. I took first year Latin at SUNY Purchase and then continued studying privately with the same professor—R.M. Stein, with whom I also became friends, and to whom the translation is dedicated. I studied with him for an additional year to fulfill the language requirement. Since he knew I was a poet, and he appreciated contemporary poetry himself, he thought the best approach would be to read through the Classical Roman poets. We read primarily in Catullus, Ovid, and Martial.

After completing the language requirement and getting my BA I found that I had become “addicted” to reading Latin and I proposed to Bob that we continue our tutorial. At this point he thought it would be a good challenge to tackle Virgil. I found the idea of reading a great epic exciting. We spent about four additional years and read the first three books of the poem fairly intensively. We then read selections from several of the other books (though mainly we stuck with the first half of the poem). My goal in all this was not initially to translate the poem, but rather to use the discipline of reading Latin as a way of enriching my own poetry, and as a way of reading one of the great works of the Western canon.

Then in the late 1990s I decided, on a whim, to try my hand at a translation of Book II, Lines 668–804, a passage that had always fascinated me. I sent it to a few magazines, including NER. I was lucky in that Stephen Donadio, the editor at the time, found it interesting enough to publish. Stephen’s acceptance encouraged me to translate more selected passages and to put more energy into them and make them truer (in every sense of that word) to the original. It was only subsequent to publishing a couple more excerpts in NER that I decided to try a whole book, and started with Book 2. This was a big challenge, and helped me to develop a more realistic and accurate approach to the poem. Since then I have translated the entire first half of the poem (though not in numerical order), and have published all six books in NER. I feel extremely fortunate to have done so.

CK: Do you plan to finish translating the epic in its entirety?

IG: I’m keeping an open mind. One thing I do know for certain is that I want to keep translating the poem. Since there are six more books, and it takes me a year or two to translate one, it could be quite a while before I finish a version of the whole poem (though I could probably do it faster if I had some sort of external incentive). I am mainly translating the poem for pleasure, for its positive impact on my own work, as an ideal way of reading the poem, and for the satisfaction of publishing in magazines, when and as that happens.

CK: What other translations of the Aeneid have you read, and how do you think yours is different?

IG: I have read the major recent translations of the Aeneid (Fagles, Fitzgerald, and Mandelbaum) and while translating I often refer to those translations, as well as to a literal prose translation (Fairclough) to see how other translators have handled passages that give me difficulties, or simply to see how another translator approaches a particular passage. Translation is obviously an approximate practice. In fact I would say that translation, on the most fundamental level, is an impossibility. No language can be expressed in the terms of another language. They are not equivalent. The most successful translation is one that best balances the technical demands of the language being translated with the attempt to create an effective approximation of the spirit of the original in the language of the translation. Of course my translation is as different from any of these others as their translations are different from each other. However, if I had to articulate distinctions I would say that mine is a bit more American, a bit less ornate, and probably a bit less accurate from a scholarly point of view.

CK: Do you have a favorite passage in Book 7?

IG: The book is full of great passages, but I think my favorite is lines 406 ff (in the original), in which Alecto, one of the Furies, whom Juno (Aeneas’s divine nemesis) has brought up from the underworld to stir up war, disguises herself as an old and trusted priestess of the temple of Juno, and appears to Turnus in a dream. She tells him that the Trojans have arrived and are a threat to Latium. In the dream, Turnus scoffs at the old woman and says she is senile and stirring up trouble. He tells her that, especially as a female, she should mind her own business (tending to the temple), in part because it is the men who must do the fighting if there is a threat. This enrages Alecto and she drops her disguise and appears as her true self—her wild face alive with horrid snakes. She screams at Turnus, pushes him, and snaps her whip. Turnus is terrified and shaken out of his complacency, startled into a more warlike mood.

In general Virgil’s depiction of Alecto is, for me, a highlight of his writing in the book, and shows that although the latter six books of the epic are less finished, Virgil’s writing in them retains much of its power.