Current NER summer intern Simone Edgar Holmes ’20.5 talks to Jake Risinger ’06, former NER intern and current Assistant Professor of English, about teaching, listening, and Lord Byron.

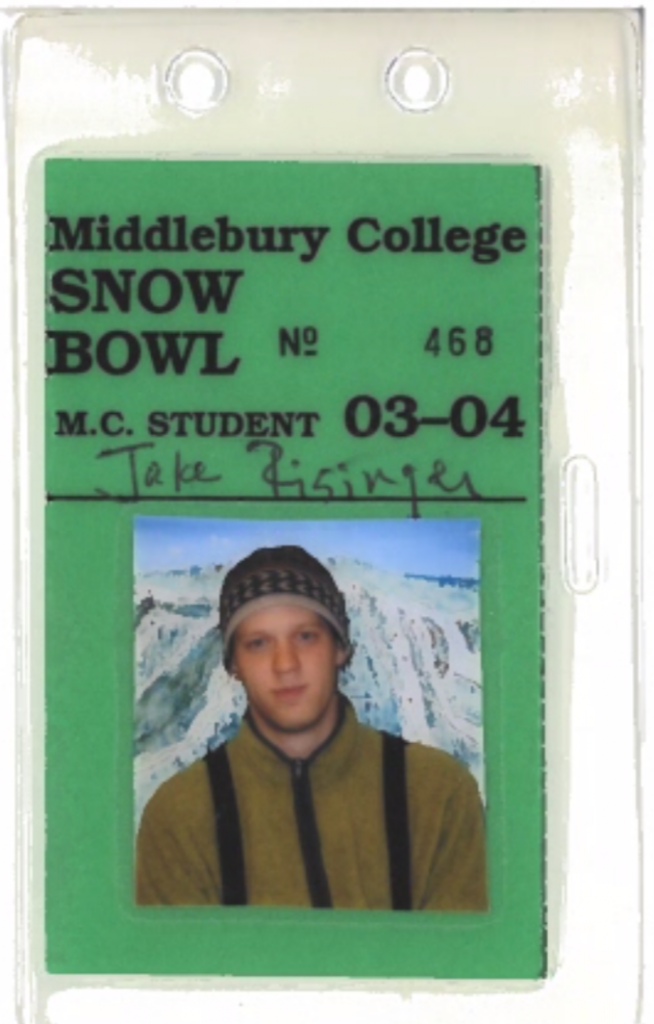

Jake Risinger, pictured now (left) and during his time at Middlebury (right), ready to hit the slopes.

Simone Edgar Holmes: When were you an intern at NER and what do you remember from the experience?

Jake Risinger: I worked for NER in my last year at Middlebury, starting in the fall of 2005. My recollection is that the position was pretty nebulous at that point in time—not really something you applied for, but an experience I sought out. I’d just come back to campus from a year abroad at Oxford University, where there was a seemingly endless line-up of readings and literary lectures, and there were all kinds of journals and literary magazines ready for perusal on the shelves at Blackwell’s bookshop. It seemed like literary history was unfolding all around you all the time. Back in Vermont, the New England Review seemed like this comparable blast of literary and intellectual life always unfolding in a quiet corner of campus. NER was over in Kirk Alumni Center at that point in time, and I remember large piles of paper submissions in their manilla envelopes (and the wonderful assortment of stamps that came with them). There were quiet afternoons of copy editing and at one point Carolyn Kuebler gave me the enviable “job” of reading around in other journals in quest of new ideas for best practices. On one particularly memorable afternoon, we cleaned out NER’s self-storage locker at a place up on Route 7 North, a garage stuffed full of chapbooks, back issues, journals, and other literary odds and ends. I think I made out like a bandit…

SEH: You’re now an Assistant Professor of English at Ohio State University. What were some steps you took to get to where you are now?

JR: After Middlebury, I went back to the UK to get my master’s degree, and then I spent a year working at a bookshop in Virginia. Working at a bookstore had its own kind of melancholy—proximity to books without much time to read or talk about them. So I filled out grad school applications and started my PhD at Harvard the next fall. For most of those years, my partner Memory and I were “dorm parents,” living in a freshman dorm and looking after first-year students. We’d walk our dog around Cambridge and then come back to make late-night grilled cheese for thirty students. I suppose most of my post-college life has involved thinking and writing about literature, but also (crucially) engaging with students. I trace a lot of this habit of being back to Middlebury: when I’m teaching, I still think quite a bit about what it was like to be a student.

SEH: I hope to be a professor (of art history) someday, so I’ll do my best to keep this advice in mind! My next question is about your area of expertise: Romanticism. What first sparked your interest in this literary movement?

JR: When I was in high school, I was blown away by hearing the last few lines of William Wordsworth’s “Intimations Ode.” I couldn’t get them out of my head, but I didn’t come close to understanding their urgency or significance until I got to Middlebury. Bob Hill and John Elder introduced me to the wider world of Romantic literature, and I haven’t looked back. In Bob Hill’s class, he asked each of us to write down a real, legitimate question on a scrap of paper at the end of every class. He’d collect these, and start the next session by riffing on our scraps of questions. I still have loads of questions about this influential moment in literary history and I just keep asking them.

SEH: You teach some fascinating courses––“Ecopoetics: From the Enlightenment to the End of Nature,” “Before Night Falls: British Poetry, 1750–1900,” and “Lord Byron and His Circle” to name a few. Which one is your favorite to teach and why?

JR: When I pitched the idea of teaching a course on Lord Byron, I was worried that no one would sign up. Byron was world famous in his day, infamously “mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” but he’s never been a staple of college syllabi. I’ve had the chance to teach this course a couple of times now, and it’s always a riot—certainly one of my favorites. For one thing, Byron was a comedic genius, skilled at the subtle art of throwing shade. His irony cuts down anyone who purports to know all of the answers, a move that puts any professor trying to explain Byron in an awkward, almost hypocritical position. All of this destabilization makes for great, open-ended discussion. Talking about Byron puts all kinds of topics on the table: the relationship between literature and history, the performance of gender, the rise of celebrity culture, or even what seemed like an almost impossible task: the desire to write an epic in a seemingly unheroic age. It’s hard to read Byron without finding traces of our own world everywhere.

SEH: I wish I could take this course with you! What was one skill you developed as an undergraduate that most benefits you today in your professional work?

JR: In my field, we talk a lot about teaching students how to write. And at some universities you can still take a course in public speaking. But let me make a claim here for the value of listening. It’s one thing I loved about my best seminars at Middlebury—that point of absorption where you stop thinking about what you could say next and instead listen intently to what someone else is saying. This is so vital to teaching. When we are all really listening, we can start really talking. And that’s when real understanding becomes possible. Obviously our world is greatly in need of more careful listening.

SEH: What is your favorite genre to read for pleasure? Have you read anything exceptional lately?

JR: Since I spend a lot of time teaching poetry, I tend to gravitate towards novels for free range reading. At the moment, I’m engrossed by Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light and Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School. Another recent favorite was Hernan Diaz’s In the Distance.

SEH: Thank you so much Jake for sharing your experiences, recommendations, and words of wisdom.