Our nonfiction editor reflects on the movies as a binding force for good, and NER offers a sold-out issue for free, including our first film supplement.

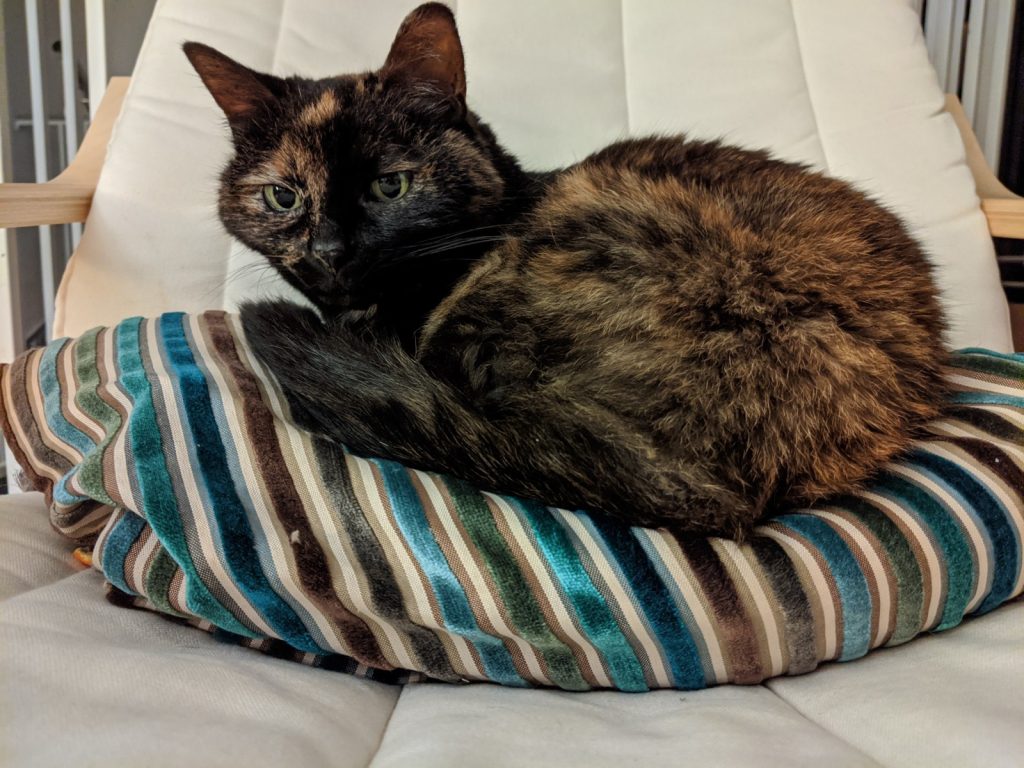

Inside all day in the nation’s capital with my novelist wife and our anxiety-ridden tortoiseshell cat, I keep getting e-mails with suggestions for films I ought to watch during the pandemic. Sharing movie ideas with far-flung friends and with my wonderful film students brings me a sense of solace and normalcy when the whole world is going haywire. This blog post contains my viewing journal for a plague season. It is my version of “what to watch while you are trapped at home and bored/terrified/losing your gourd/feeling desolated and crazed/trying to stay positive/succumbing to despair/donating to hospital charities/knitting a masterpiece scarf that doubles as a face covering.” I really don’t mean to sound flip—I’m barely holding it together much of the time (refresh, refresh, refresh). We are the privileged ones lucky enough to stay at home while unbearable suffering continues to unfold all around us.

I make no apology for my decision to recommend whatever strikes my fancy, whether or not it seems “relevant,” “appropriate,” “relatable,” or any of those other soul-killing terms. Given NER‘s literary mission, it makes some sense to foreground adaptations from the page to the screen. But I am not feeling sensible, so I will not be following that plan. I’ve named this post “Remote Viewing” for obvious reasons, given the circumstances of a world without open cinemas and popcorn machines. That’s one very small and insignificant aspect of this general heartbreak and these are my love letters to films that I miss sharing. I enjoy being with other people when they watch a great film for the first time. I like listening to how it affects them to experience art in the same room—and then hearing them talk about it afterwards. I miss everybody!

The series to watch right now, if you can bear it, is HBO’s devastating account of nuclear error, Chernobyl. And, if you cannot bear it, then watch the hilarious HBO space farce Avenue 5. Actually both shows are about the same thing, which is precarious oddballs risking their lives to save people who are threatened with imminent death due to the rank incompetence and lies of their leaders during a disaster. In fact, that’s what every film is about now, or so it seems, from A to Z—from Ridley Scott’s blockbuster Alien (1979, don’t break quarantine, you fools!) to Lucrecia Martel’s latest masterpiece, Zama (2017), which among other things memorably features an outbreak of disease in eighteenth-century colonial Argentina.

I, too, have noticed lately that few characters in cinema, from the denizens of the ship in McCarey’s An Affair to Remember (1957) and the blue people of Cameron’s Avatar (2009) to the serial killer in Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) and the psychedelic desert orgy-goers in Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970) are practicing responsible social distancing. I view every movie through this double lens right now. I suppose the accidental exceptions are Tom Hanks in Cast Away (2000) and Tom Hardy in Locke (2013), two films that achieve additional poignancy at the moment, for different reasons. As does J. C. Chandor’s sea-disaster one-man show, All Is Lost (2013), if you can stand a film with that title at the moment. And then there’s the unforgettable isolation of Cuaron’s Gravity (2013).

These movies where mostly solitary figures take up almost all the space and screen time are somewhat rare, although Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1964) fits the bill and the meal-prep scenes of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975) perhaps feel closer to resembling the current cycles of endless days marked by boredom (and horrors which I won’t spoil). If you are fortunate enough to have the time, this era of self-isolation might well provide a unique opportunity to take in the full power of such films and to see them in a new light, as riveting dramas as driven and compelling in their extraordinary internal poetic logic as the chase scenes in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015). The big sister, Elsa, in Frozen (2013) also had the right idea—if anyone needs me I’ll be chilling in my ice castle.

Okay, now that I have established myself as a serious critic with a clearly defined set of tastes—sorry/not sorry, I love it all—I’m going to be so bold as to suggest that you watch nothing except what makes you feel most deliciously alive because nothing else matters and we never know how much time we might have. For me that’s always going to start with Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983), with its travels to the four corners of the globe. Marker’s narrator files quasi-fictional reports in the form of letters from the richest areas of Tokyo to the poorest markets of the Cape Verde islands.

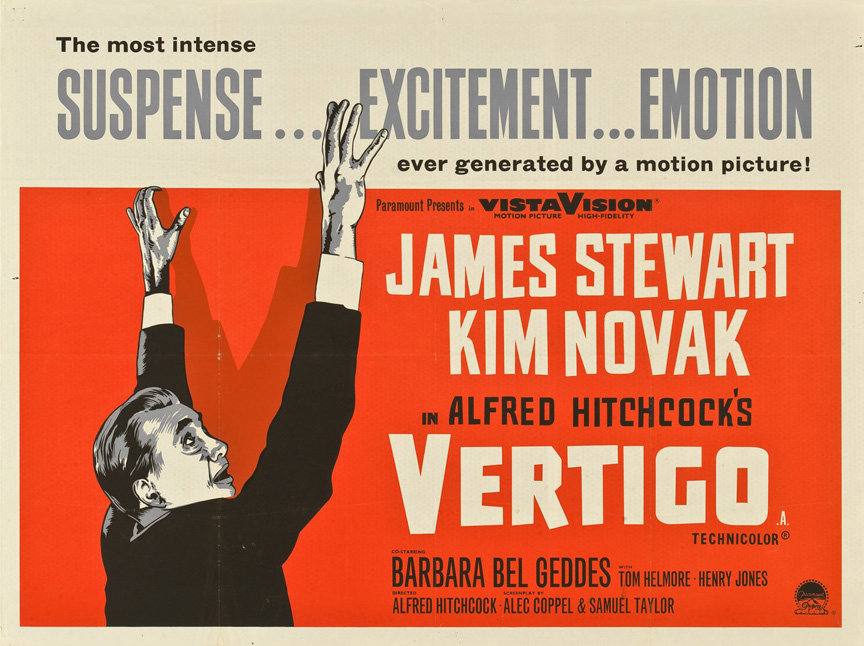

It’s a strange sort of film that seems to be a different movie each time I view it. It’s also a film of films, containing many other movies inside it, and a film about film and about television that “watches you back.” One of the most intriguing sequences records Marker retracing all of the real-life locations of another film, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), which Marker claimed to have seen nineteen times. Watching Marker tracking down Hitchcock, I always pause and replay the section about the Mission Dolores. This was the fictional location of the burial place of Carlotta Valdes, who is believed to be a possessing spirit from beyond the grave, like Rebecca in the 1940 film named for her, and somewhat like Norman Bates’ dead mother in Psycho (1960). In one sense many of us are currently living a little too much like Norman now, cooped up with our ghosts and unable to leave the grounds, “lighting the lights and following the formalities.” We’re the proprietors of empty businesses like the Bates Motel, with its “12 cabins, 12 vacancies.”

When I see the Mission Dolores, I am transported back in time to my loveable old haunted sublet on 16th Street, where the Mission bells were a regular aspect of my routine. The place had a ghost cat and the bedroom shivered during smaller earthquakes. I once found a child’s tooth in a drawer that I was convinced had not been there the month before. When I’m watching Vertigo, or Sans Soleil, I fully expect to see an image of myself haunting the edges of the picture, like the extra ghostly space inhabited by otherworldly figures at the margin of the screen in The Ring (2002).

In another sequence from Sans Soleil set in Japan, Marker quotes Brando’s Kurtz in Apocalypse Now (1979) as he watches the film on television: “You must make a friend of horror.” Indeed, we must, yet we cannot manage it. This hideous virus attacks everything that makes us human, in particular our need for contact and love and going to the movies. It targets those who gather to mourn and to celebrate, to worship and to dance. We have to deny the horror, to look away, and to watch something else, no matter how trivial or profound. That’s one thing films are good for, but films can be more than distractions, of course. They are mirrors, portals, doors that we can open and pass through into the world and ourselves and the past.

Marker claims Vertigo as the only film that captures what he calls “impossible memory, insane memory.” But Marker is being characteristically modest. His own film is the only one that does that for me, or to me. Now that I cannot go anywhere, I feel like disappearing into this film altogether. Impossible and—yes—slightly mad. “We all go a little mad sometimes.” -Norman Bates.

Marker’s heart-stopping opening sequence features an “image of happiness,” three children walking along a road in Iceland holding hands. Later, Marker’s footage returns to Iceland to show how a volcano filled a fishing town with lava, up to the rooftops in some cases.

I’ve never been to Iceland but this form of “remote viewing” or tele-visual “action at a distance” gives me the chills. What makes the film all the more remarkable is that Marker created it without any scripted scenes, actors, lights, dialogue, producer, or studio. It’s a film that presages the whole DIY YouTube/smartphone video upload ethos. Could it or something like it be made today? I think so, if you already had the footage gathered from many years of travel and suddenly found yourself with nowhere to go.

Yet to watch Sans Soleil now is to experience one peculiar heartbreak of our shared moment in which travel is impossible, both dangerous and seemingly trivial. But making future plans, however banal or luxurious, feels vital at the moment. I promise myself that I will finally visit Iceland when all this is over. Then I consult the pollution charts and see the planet breathing a little bit better now, and I make a vow to travel by cargo ship. Then I remember my horrible tendencies towards seasickness and vertigo. Then I recognize that I’ll likely be inside most of the time from now until . . . who knows when. Right now that’s the definition of a happy problem formed by a sense of privilege now revealed in its full obscenity. Then I realize how everything I’m thinking and feeling today will pale into insignificance tomorrow as the next phase of the crisis unfolds. We’re told that staying home saves lives, but it’s difficult not to feel useless or even burdensome. Even if doing nothing (which is impossible in any event) is said to minimize the harm we pose to others just by exhaling, we’re putting the lives of precarious workers at risk every time we place a delivery.

“Was it for this?” Wordsworth keeps asking in the first version of The Prelude (1799). Was what for what? And what can art do? I really have no clue, but for me art means there must be a future. I’d like to think that there is more to the belief in movies as a binding force for good. As one great line goes in Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (1942), a film that dares to joke outrageously at the darkest hour, “A laugh is nothing to be sneezed at.” We need Lubitsch’s sense of fun more than anything, and it is in very short supply.

I’ve been reading that the Germans (who else) have a term for this feeling I’m having a lot right now, fernweh, a “farsickness” that counterpoints homesickness. As far as I understand the term, fernweh conveys a feeling of yearning for unexplored distant places—and, presumably, an enduring feeling of heartache related to missing all the things and people in those places that we feel we might never encounter. That is how it feels to me to be alive—alive!—in April 2020.

Interested in reading more about film? In summer 2018 we published a feature on Terrence Malick, including ten writers’ and one illustrator’s views on his films, from Badlands to Song to Song. To help you through the time with no movie theaters, we’ll be happy to send it to you for free! Click the following link and download NER 39.2 to your computer or mobile device:

E-pub for your iPad, iPhone, Nook, or computer.

MobiPocket for your Kindle.

J. M. Tyree is a nonfiction editor at NER, a contributing editor at Film Quarterly, and teaches at VCUarts. He is the coauthor of Our Secret Life in the Movies (with Michael McGriff), an NPR Best Books selection, and BFI Film Classics: The Big Lebowski (with Ben Walters). He is the author of BFI Film Classics: Salesman and Vanishing Streets – Journeys in London.

Above: The author’s shared working space.

Photo captions for the gallery at the top (left to right, top to bottom):

Vertigo – Hang in there, kitten.

Chris Marker’s “image of happiness.”

From Marker’s Sans Soleil.

The author in a vanished era.