On Dennis Oppenheim | By Scott Nadelson

Not long ago, on the first anniversary of a close friend’s death, I pulled a disc from my wife’s collection of film and video art. She’s a video artist herself, and her collection is extensive, but when I went to her shelf I didn’t know what I was looking for, only that I wanted something visceral to reflect or contain the grief I couldn’t express.

The piece I chose to watch was Disappear by Dennis Oppenheim, who himself had died around the same time as my friend. By then, at the age of 72, Oppenheim had become a monumental figure of conceptual art, known best for large sculptural projects like Device to Root Out Evil, a small church-like structure standing on its steeple. Disappear dated from early in his career, when he was exploring the possibilities of both the body and the moving image as media, and of all the work to come out of the explosive and vibrant experimentation of the late sixties and early seventies, it’s the piece I find most moving, striking the perfect balance between concision and complexity, between aesthetic considerations and emotional ones.

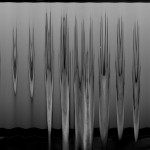

The piece, shot on black and white film, opens with the image of a hand moving against a blank background. “I don’t want to be able to see myself anymore,” a voice says. “I want this part of me to leave.” The hand moves faster, blurring, becoming skeletal, even translucent, as the flash of shutter opening and closing, twenty four frames per second, fails to keep pace with it. The voice-over splits into two tracks, speaking different lines of the same monologue, one expressing desire to vanish, the other witnessing a transformation in process: “It’s gone, my hand is not accessible to sight.”

The film is six minutes long. The hand keeps moving, the voice keeps speaking. The combination of sound and image conveys despair, a longing for oblivion that comes with the exhaustion of living, a longing I now associated, while watching on the anniversary of my friend’s death, with grief. At the same time, there’s a striving for transcendence in the speaker’s words, a need to reach beyond the limitations of the physical body, of individual thought, to discover spiritual possibilities lurking in the void. And the piece achieves this transcendence visually, as the moving hand becomes a beautiful dancing abstraction, a Franz Kline painting come to life.

The longer I watched, the more the piece consoled me. And this is why: the hand never disappears entirely, no matter how fast it moves. As long as the camera stays on, as long as film rolls, and most important, as long as a viewer watches, it stays in partial sight. As do all things that leave this world.

*

NER Digital is a creative writing series for the web. Scott Nadelson is the author of three story collections, most recently Aftermath (Hawthorne Books, 2011). His first book of nonfiction, The Next Scott Nadelson: A Life in Progress, is forthcoming in March 2013.