Koch’s Postcards | By Kate Petersen

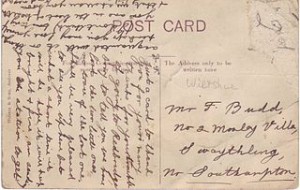

I suspect I’m not the only writer who has found herself stuck indoors on a nice day, not writing, but in some musty corner of an antique shop, thumbing through a little tray of old postcards, the free-with-purchase flotsam of estate sales, obsessively reading messages which seem by turns banal and epiphanic.

It’s strange what the commerce of the bygone and the dead does—how the voyeurism of reading someone else’s mail is made safe there beside crumbling hatboxes and flocks of porcelain birds. I’m ashamed to admit I’ve even felt charitable once or twice, reading these strangers’ wish-you-we-heres, as if I’ve completed a broken act of communication, reset some old and minor bone.

And so Kenneth Koch’s “The Postcard Collection,” invites the reader into a game she thinks she knows. But the piece, first published in Art & Literature in 1964 and later anthologized in The Poet’s Story (1973) and The Collected Fiction of Kenneth Koch (2005), becomes a singularly Kochian experiment in epistolary forensics and fancy:

“On the first card,” the piece begins, “which seemed to be a French one from around 1928, which had already been sent through mails and had writing on the back, was a picture of an old woman in a yellowish pink dress holding a watering can and bending over some flowers…”

This descriptive exercise unwinds quickly, trips and blossoms into a meditation on art, metaphysics, and Koch’s signature question: how to be a body in the world and, at the same time, a mind, a soul:

Everyone is walking up and down the streets, with warm thighs pushing upwards and outward through pantaloons and dress, faces moving, and the air, the air hovering expectantly over all. What do you want to do to us, air? eat us?

We recognize such flights of language from Koch’s poems, though here, the language doesn’t rest or come up for air the way it does in, say, The Art of Love. Though the conceit is one of untangling the mystery of the postcards, Koch’s prose operates in the opposite way: knotting itself up in sentences that seem made by someone who, having forgotten how to make a cat’s cradle, is gleefully left holding all that string.

I picture the speaker stationed at his writing desk with a musty shoebox before him, thumbing through old French postcards he’s collected along the way. The speaker moves painstakingly from one card to the next—four in all—poring over each detail for clues about the sender and recipient. As he fills in the smudged or unreadable parts, the narrative slips between past and present tense, underscoring the modest time travel that reading such cards permits us. On the way, he invents not just senders and recipients, but a deficient poet (who may be named for a real 19th-century French historian), his editor, a school of poetry, a young adolescent devotee of Verlaine, and an aunt who wishes to point him towards a more “sexless” poetry. I am making an argument about humanness and how to be an artist, Koch seems to say over and over again, but I am also making fun.

It’s a project we know from his poetry: Silliness is not a diversion, but an arrow towards what is the matter.

These “gyrations of thought,” the narrator says toward the end, “are part of a process, and how can I be sure the flowers will continue to turn and to glow in this now dusty graying air were I to cut off a piece of their stems, not to say anything of their roots.”

At one point he concedes that “postcards themselves are a self-mockery, and a disguise; so is all art; so, for that matter, is talking through the vocal chords, the trachea, the epiglottis.” Art is forced to be somatic, he says, though it is no more real for it.

Yet we begin to understand that the piece is a postcard itself, addressed to a you, a love: Writing letters may be a foolish and philosophically bankrupt enterprise, yes, but one which nevertheless speaks of “a desperate attempt to project oneself into such a world…in which it is actually possible for one to ‘go somewhere.’”

Formal categories, if they still exist, may no longer matter. And “The Postcard Collection” both is and it isn’t a story: stationed in the poetic ‘I,’ it’s interested—keenly so—in other fictional characters, among which Koch counts poems themselves:

‘It is very bad for me to be left in here’—so says every message on every card and in every poem in the world. But what way is there to set them loose like swallows?

And here, I look up from the card in my hand, this stranger’s words, confounded, unable, as ever, to reply.

*

NER Digital is a creative writing series for the web. Kate Petersen’s recent fiction and nonfiction have appeared in NER, Paris Review Daily, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives and teaches in Minneapolis.