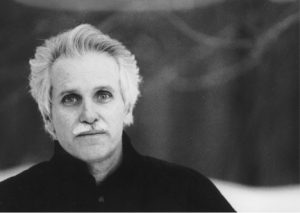

Editor Carolyn Kuebler talks with Peter LaSalle, author of “Conundrum: A Story About Reading,” about realer-than-real realism, fiction, and the lasting power of John Updike’s Rabbit, Redux.

Editor Carolyn Kuebler talks with Peter LaSalle, author of “Conundrum: A Story About Reading,” about realer-than-real realism, fiction, and the lasting power of John Updike’s Rabbit, Redux.

CK: “Conundrum” is, as it says, “a story about reading,” but it is also about memory and dreams and the way all of these layers of our interior lives get mixed together. It’s surprisingly rare in a piece of fiction for a character to interact, in such intimate and complicated ways, with a specific book, the way your narrator does with Rabbit Redux. Why do you think that this kind of book talk is usually relegated to reviews, criticism, essays—possibly memoir—but is so unusual in fiction?

PL: I know what you mean, that such commentary about books is typically confined to literary outlets other than fiction. However, when you think of it, if books play such a big role in many of our lives, there’s no reason why they shouldn’t provide a subject as valid for fiction as the pursuit of a proper marriage based on the financial circumstances of the landed gentry (e.g., Jane Austen) or the certainly more harrowing pursuit of an enigmatically snowy whale all over the South Pacific.

Borges was one writer who fully realized this. He was a librarian in Buenos Aires by trade, surrounded by books and often admitting his life was more about books than what passes for actual living. He had scant success in love, never made that much money, yet, man, it seems he’d read almost everything, ventured far into the mysteries of the human psyche via that particular pursuit. Therefore, reading—along with what you call book talk—is the subject of a good deal of his fiction. And, needless to add, it’s fiction that has become some of the most startlingly original writing of the twentieth century, a story like the classic “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” being a prime example.

CK: Could “Conundrum” have been about any book that you’ve read, or is there something about Updike that set this story into motion for you?

PL: Well, Updike’s work has bowled me over ever since I started reading it way back in college. I remember my roommate left lying around our dorm room a well-worn paperback copy of Couples, a book considered quite racy at the time, and I was amazed then by what has amazed me ever since in Updike’s writing—the keen social observation and solid sense of structural craft, also such a rare gift of language.

About a year ago I set out to reread just about all of the major novels in his vast oeuvre, finally deciding yet again that Rabbit Redux, a tour de force set in the turbulent late 1960s, stood out as his very best. As the result of that, I guess, and more or less drunk on the wonderful power of his jeweled prose, the story “Conundrum” took off in my mind from there. The idea was to have somebody recommending a book—in this case Rabbit Redux—to somebody else, and then that other person passing away before he has a chance to read it. Then somehow, as in a dream, the two of them rectify that misfortune and eventually find themselves in another zone of perception altogether; there, with chronological time denied as maybe the flimsy premise it is, the book gets read aloud by the recommender—the story’s narrator, an unnamed, worn-out journalist who briefly studied for a PhD in literature when young—to the other person, his deceased brother-in-law Bill, a guy who worked his whole life in a print shop and always loved reading. They have long conversations about specific passages in the book, and the recently deceased Updike himself—smiling, characteristically charming—eventually shows up to contribute to the discussion as well. I mean, why not?

CK: For your narrator, the experience of reading is imperfectly remembered, rooted in a time and place, filtered through actual dreams, and the basis of his connection to another person. Because that seems pretty much how reading works for me too, this story feels like a kind of realer-than-real realism. Another of the story’s questions seems to be, what is reality anyway? To you, what makes a work of fiction most “real,” or most engaging in terms of this question?

PL: I do like the way you phrase it, “realer-than-real realism,” which possibly means going beyond realism to evoke something truer. And it sort of describes exactly what I’m after in this story, as well as with much of my writing in the three short story collections I’ve had the good luck to publish in the last ten years or so, including the book that I hope is the most daring of the trio, Sleeping Mask: Fictions, which came out this past winter.

I want to use the tools of fiction to tap into the metaphysical, as common assumptions about a lot of things—time and space, reality versus unreality, even the distinction between life and death maybe, as in “Conundrum”—are questioned. It involves seeing fiction as an opportunity not only to provide entertainment, which is important, but also to embark on larger explorations. The approach seems akin to how a scientist might go into the lab, or a theoretical physicist might start chalking away some complicated, mile-long formula on the blackboard and suddenly have it lead to a totally fresh, unexpected revelation, what goes beyond clunky deductive logic and, yes, metaphysically, strikes one as truer than true, realer than real indeed.

That said, I realize I shouldn’t let myself get tangled up here in attempting to explain too much when it comes to any concept of reality, which is beyond merely being complicated and most likely never can be properly explained, only experienced. That’s the inherent magic of it. Probably it’s enough to simply ask Maestro Borges to step into the witness box once more, with his great quote that succinctly gets at the heart of the matter: “We accept reality so readily, perhaps because we suspect nothing is real.”

CK: Books (and other art forms—movies, music, etc.) become a part of who we are, as this story suggests. You’ve also written a lot about travel. Do you think that travel plays a similar role as art? Is the experience of travel, or of recalling a trip years later, anything like the experience of reading a book for you?

PL: Travel has been important to me throughout my adult life, usually as purposefully conducted solo. And I strongly believe that both reading fiction and traveling alone have a spooky something in common, their both entailing entering into an unknown territory (the pages of a book, the places in a foreign country) and never knowing what you’ll encounter next—entirely dreamlike, I’d say.

Not to sound like I’m shilling my own various books here, but a year or so back I published a collection of essays that involve travel as it transpires when focused on literature, which seems to relate to what we’ve been talking about. The collection, The City at Three PM: Writing, Reading, and Traveling, mostly contains essays I published in magazines over the years and that document a particular kind of trip I take. I pack a small gym bag with enough clothes for a couple of weeks and books by an author from another country, to reread the work in the place where it’s set, on the premises, so to speak, and see if anything different happens. I’ve gone to Paris to reread surrealists Breton and Aragon there, gone to Tunisia to reread Flaubert’s wild novel about ancient Carthage there, even, and of course, gone to Argentina to reread Borges there. I usually write an essay about each trip, plus acquire new ideas for fiction.

Now that I think of it, travel does figure into the rather dreamlike machinations of the story “Conundrum,” where, if you remember, the journalist narrator, once a New York newspaper’s foreign correspondent, tries to pinpoint where he seemed to be in the odd dream he had about Rabbit Redux, finally concluding it was Istanbul. In fact, that’s another place where I also spent time recently, going there to meet with the translator of one of my books as well as to thoroughly immerse myself in that country’s fine literature.

CK: You mentioned that you’re reading contemporary Vietnamese literature now to prepare for a trip and to meet writers there. What are you finding so far? What are your plans for that trip?

PL: Yes, this is my latest trip, upcoming.

Almost twenty years ago I reviewed an anthology called The Other Side of Heaven, edited by the novelist and Vietnam War veteran Wayne Karlin. The book built on the very original concept of providing short stories about the war by writers from both sides. So, you had Americans like Larry Heinemann and Tim O’Brien represented, but much more intriguing for me, the Vietnamese writers, such as Nguyen Huy Thiep and Bao Ninh, the latter a North Vietnam Army veteran and his contribution to the collection, “Wandering Souls,” excerpted from his internationally praised 1987 novel The Sorrow of War. The Vietnamese writers often seemed to be dealing with matters visionary, the war for them becoming a somehow ghostly experience, haunting, otherworldly, perhaps a mindset influenced by the country’s own tradition of metaphysical thought in the Taoism and Buddhism that have contributed to religious life there.

Those stories stuck with me, which doesn’t usually happen when one reviews a book simply received as an assignment from an editor. This past spring I started tracking down more Vietnamese writing, and then I looked up online an email address for Karlin and contacted him. I asked him if he remembered the review and told him I was reading all the contemporary Vietnamese fiction I could and planning on going to Ho Chi Minh City—as Saigon is now known—and Hanoi this summer to further explore that literature there. Karlin and a Vietnamese novelist whose work he’s translated, Ho Anh Thai, generously put me in touch with some writers and editors to meet with in Vietnam to discuss the country’s literary scene. I’m definitely looking forward to the trip.

CK: Your narrator says, “There’s nothing better than recommending a book to somebody and having them really like it.” I think a lot of readers would agree with that—do you? Can you tell us about any particular experiences of having someone really like a book you yourself recommended? Would you like to recommend anything here, to readers who liked “Conundrum”?

PL: Being a teacher, I recommend books to students all the time, to the point I suspect they probably grow tired of hearing me tell them that they just have to read this, or they just have to read that.

Nevertheless, a college creative writing teacher of mine, Carter Wilson, once casually recommended I read Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, the powerful novel about a dipsomaniac British consul in Mexico in the 1930s who conducts his own almost epic battle with the ways of the universe, unquestionably a masterpiece of late modernism. It turned out to be one of my all-time favorite books, has been very influential when it comes to my own writing, too. So I guess one never knows if a suggested title a student jots down in a spiral notebook yanked out of a book bag while chatting with a teacher during office hours will, in fact, have at some point a similar pretty massive effect, right?

I will say that in general I’d recommend to young creative writing students especially that they read daring, even overtly experimental fiction, which in turn might spur them to be adventuresome in their own work, take risks and not settle for the more commercially viable formulaic. Or, to put it another way, make them want to explore in their writing the limitless potential of fiction as true art and not just the predictable mainstream stuff that literary agents and conglomerate-owned publishers nowadays tend to be attracted to, convinced that big money might be made by sticking to what’s safe. It nearly broke my heart a few years ago when I had a seminar class of bright, talented graduate MFA writing students at the University of Texas where I teach and I asked how many around the table had read Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, to see only two out of a dozen raise their hands.

I could add a ten-page list here of books I’d recommend, or maybe a twenty-page one, but for the moment let me only say—or shout to anybody willing to listen—please read The Sound and the Fury if you haven’t already. Don’t let another moment in what for any of us is our brief time on this sweet planet pass without the undeniably rare experience reading a brave book like that can be.

Actually, to maybe bring this all full circle and return again to my NER story  “Conundrum,” it would be so good if the story possibly turned somebody on to reading Rabbit Redux, a novel extremely risk-taking in its own way. And I suppose that if “Conundrum” did inspire at least one reader to go out and get Updike’s book, such might be the ultimate kind of success for my story that I surely would hope for.

“Conundrum,” it would be so good if the story possibly turned somebody on to reading Rabbit Redux, a novel extremely risk-taking in its own way. And I suppose that if “Conundrum” did inspire at least one reader to go out and get Updike’s book, such might be the ultimate kind of success for my story that I surely would hope for.

CK: Thank you, Peter.

PL: And thanks go to you, too, for the really good questions.