Nonfiction from NER 42.3

Subscribe today!

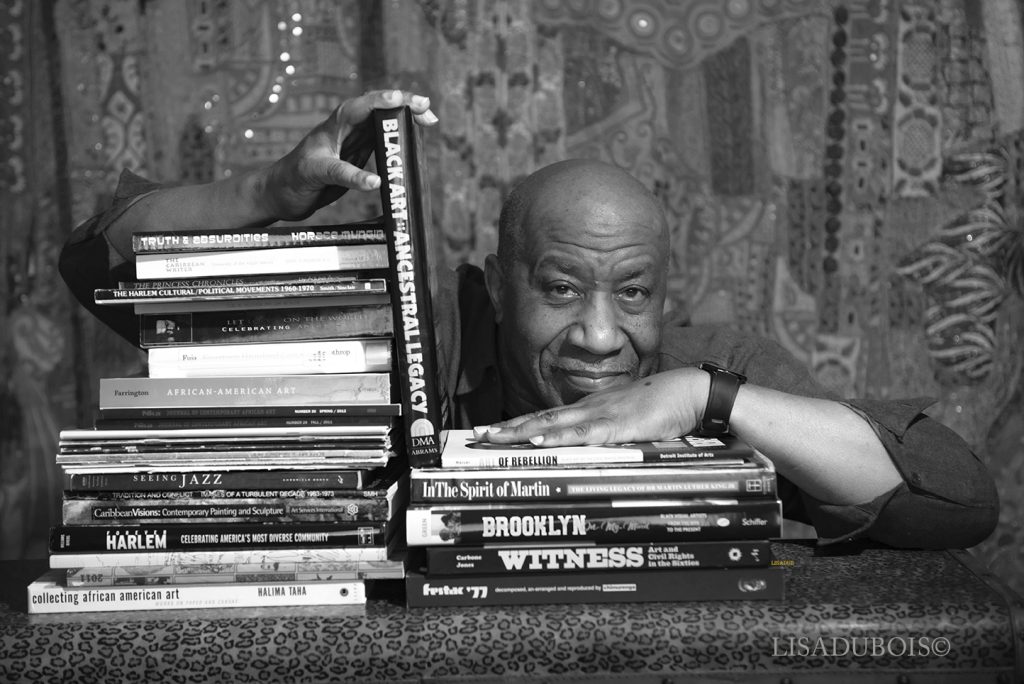

A recent portrait of artist Ademola Olugebefola with a few select books and museum catalogues that include his art and career achievements. Photo by Lisa DuBois.

A

demola Olugebefola (Bedwick Lyola Thomas) is an educator, activist, and multitalented artist. His versatility encompasses graphic design, illustrations, theater set designs, woodcuts, lithographs, etchings, serigraphs, oils, ink, charcoal and pencil drawing, free-standing sculptures, and murals, among other artistic forms. His works have been featured nationally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, galleries, museums, and universities. During the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, he was politically active and became one of the founders of the Weusi Artist Collective. He later became a cofounder of the Dwyer Cultural Center in Harlem. Early in his career he was a musician, but ultimately he focused on the visual arts and has had a long career as a theater designer, where he collaborated with prominent Black directors, producers, and playwrights. His journey as a visual artist continues to this day. I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with Ademola Olugebefola at his office in the Dwyer Cultural Center in Manhattan, July 1, 2020.

NGN: How did your training to be a visual artist begin?

Ademola Olugebefola: When I was eight or nine years old, we were living in Brooklyn on Grant Avenue—we had just immigrated from the US Virgin Islands— and, as I recall, I asked my mother, Golda, to draw me a horse. She did it effortlessly, and that began my journey. From there I took art classes in high school and junior high school, where I used to draw political cartoons. Then I developed an interest in fashion because my mother and my aunt made their own clothes, so I went to the High School of Fashion Industries. And, of course, there you had to be able to draw. After that, my teaching came out of the Weusi Artist Collective and Academy and the association with other artists, in particular Otto Neals. The Weusi was the gathering of artists from the New York area; we formed Nyumba Ya Sanaa Academy of African Arts and Studies. But after my mother did that horse, I drew horses for the next fifteen years. That was my initial training, and then there is a certain amount of natural affinity I had for drawing.

NGN: I understand that you were also a musician, and your involvement with music began in high school. You sang, played drums, and played the acoustic bass. How did this come about for you?

AO: I grew up in Amsterdam Houses in Brooklyn, which is where a lot of Caribbean people landed in the 1940s, after World War II. There was always music in my house; my mother loved music; my father loved music. As I was growing up, rock-and-roll, rhythm and blues were very prominent. My singing in those days was part of the doo-wop—singing on the corner, singing in the hallway with my friends. I loved music, there was nothing more wonderful than when you hit a note and you heard that harmony; that was my high. Then I had a girlfriend, the mother of my oldest daughter, who was a jazz aficionado. When I listened to Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue” and heard Paul Chambers, the world changed for me. I just loved his rhythm, his sense of melody, which really got me wanting to play the bass. Some of my colleagues and friends of that period formed a group—I’m going back to the mid-1950s now. One of the things that was very influential at that time, with all of us, was that I could look out my window from our apartment and see the Phipps Houses, where Thelonious Monk lived. I used to play with his cousin, ran track and played basketball with his nephew and niece. Thelonious Monk was a real impetus for us all to get into music. After we formed the quartet, I bought myself a bass and started teaching myself. Then later I studied bass with Attila Zoller and developed to a point where my group played professional gigs. That went on for a number of years. I would play around with the drum, but I did not really play the drums. The singing was when I was much younger, though with the singing group, we were very serious. I remember auditioning to see if we could cut a record, in a group of studios down on lower Broadway, and hearing Jackie Wilson before he became famous. That is the extent of my singing career; but for the bass, I played professionally for a number of years.

NGN: Later you became a set designer. How and why did you move in that direction?

AO: My first set design was West Side Story for an after-school program down at Amsterdam Houses at PS 191, which is still standing there on Sixty-First Street. There was a young woman, Jean Parnell, who came in as a teacher and counselor. She was a dancer and choreographer at that point, and was also involved in teaching theater. Because people already knew that I was interested in visual arts, I was asked to design the set of our production. I designed a set out of corrugated cardboard boxes and painted them. That was my first experience at set design.

NGN: What was it like to do the set for Charlie Russell’s Five on the Black Hand Side at the National Black Theatre, when they first opened in 1969, and did you have any idea at the time that it would go on to become an important Blaxploitation movie in the early 1970s?

AO: My recollection, from fifty years ago, was that because of the lack of funds (a budgetary condition that was always typical of Black theaters) I had to improvise using purchased and scrap lumber, black cloth flats, and house paint to simulate a “nuanced” urban setting. At that time, I had no idea that Charlie Russell’s growing fame would merit his work getting to the silver screen.

NGN: Growing up, what were the elements of your visual experience that stimulated your interest in designing sets?

AO: I’ve always looked at things from plane and color. That was a natural part of my being. In that same period, back in high school, I also created sets for fashion shows, created the environment for the models to walk into. Those things all took place at PS 191 and the Lincoln Square Neighborhood Center. One of my greatest influences was Abdullah Aziz; his name at that point was Theodore Gleaves. When I was growing up, down on Amsterdam Avenue, the drugs really began to come into the neighborhood, a real epidemic, and those were the days of gang wars and all of that. Abdullah actually lived up in Harlem, but he would come down to Amsterdam Houses because he was part of one of those gangs. But he also was a painter and an artist, and he always expressed that. I and one or two others really were attracted to that alternative to the drugs and the gang fighting. That, more than anything, influenced me to want to go into the visual sciences.

Ademola Olugebefola with Bob Macbeth, founder of the New Lafayette Theater (Harlem, 1970).

NGN: Did you ever study production design?

AO: During the Carter administration there was a second renaissance of the WPA, the CETA Arts Program. I guess unemployment was high and the government then allotted millions of dollars throughout the entire country to hire creative people, in theater, music, visual arts, poetry. Their role was to go into schools, community centers, prisons, and senior citizen centers and share their artistic experience and teach. In that process, one of the courses offered was by Kurt Lundell, a Broadway set designer, commissioned to teach the technicalities of set design. So I studied production stage design for a brief period with Kurt Lundell. I had no formal training until I met Shirley Prendergast in the production of the play Real Black Men Don’t Sit Cross Legged on the Floor at the New Federal Theatre [2005–06 season]. In order for her to do her lighting, she needed actual formal drafting. That was the first time I was pushed to actually do formal drafting, with all of the specs necessary to do a formal set design. In other words, at the New Lafayette Theatre, I was able to wing it to a degree, because I had people around me who I could tell my ideas to and I could sketch out the ideas and they would build it for me. I did not have to deal with the technical skills of drafting the set and so on. It was more organic.

NGN: You work in many mediums: etchings, woodcuts, lithographs, oils, and serigraphs; you also do pencil, ink, and charcoal drawings. You’ve done cover designs and illustrations for books and other publications. Can you talk a bit about how learning to work in various mediums helped you when it came to designing sets?

AO: As for books, I have had the good fortune of working with Amiri Baraka, and in fact have an illustration in the book celebrating his seventy-fifth birthday. I have done cover designs for Ed Bullins, and illustrations and cover designs for Sonia Sanchez. There’s a whole spectrum of writers that I have had the good fortune to collaborate with. As for set design—to me, it is a monumental living sculpture. In other words, I always looked at a set as a huge piece of sculpture that was alive, in a sense that it was interacting with the actors and musicians. I approached it from that angle and philosophy rather than trying to replicate reality. I created my own reality, of course, in cooperation with the director, the designers, and the actors. The New Lafayette was a phenomenal experience that allowed me to express myself in that way.

NGN: When you take on the responsibility of designing a set, which must both serve the script and engage the audience, what are your primary considerations, given the practical constraints of limited wing space, limited fly space, and actor safety?

AO: The playwright’s idea is first and foremost with me. What is a playwright trying to say? I take the director’s need to facilitate that vision into consideration and then, of course, the space. The difference with me is that instead of trying to replicate reality, I try to bring my conceptual framework. I have been fortunate enough to convince both playwrights and directors that my ideas expand the concept. When I take into consideration all of those things—safety, the space, the utility, the facility—I also bring my art, my vision as part of the equation. And I have been successful at that, in the sense that I have done what I think of as some very notable productions, at the New Federal Theatre and certainly at the New Lafayette Theatre. When Woodie King, for instance, asked me to design a set for him, he asked me with the understanding that he was going to get something quite different than the normal, because he had seen my work at the New Lafayette, he’d seen the work I had done for dance concerts, and so on. I have been given a tremendous amount of freedom, which has allowed me to look at set design as a work of art rather than just a replica of reality.

NGN: What do you mean when you say a “replica of reality”?

AO: I have a great deal of respect for set designers who use the traditional approach, like Edward Burbridge for instance, but I am different. In essence, as I said, I am creating a giant piece of sculpture that is alive.

NGN: Is there any specific style or aesthetic that you tend to look for in the work when you choose to design a set?

AO: I am a colorist. All the sets that I have ever designed are replete with colors because I believe the science of color is important in the consciousness, not only of the artists who are performing within those color fields or color equation, but also of the audience. The color helps the audience imagine and buy into the conceptual framework of the playwright and the director.

Ademola Olugebefola’s set for Moon on the Rainbow Shawl performed at the Henry Street Settlement, 2007. Copyright Mel Wright Photography

NGN: In the theater the script is supreme. The work of the set designer (or costume designer) must serve the play, and the director has the final say on the interpretation of the script in a production. But when a visual artist creates an artwork, their own vision and execution are supreme. How difficult is it for a visual artist who usually works alone on their own pieces to work in the realm of theater as a set designer?

AO: You have to take a huge amount of what I call humble pills. You have to work with the director. He or she has their particular ideas, of course, how things should go. You certainly have to interpret the playwright’s vision. So—unlike working in my private studio, where I don’t have to answer to anyone—I have to really answer to the playwright. I have to answer to the director, and I certainly have to answer to the actors, because whatever I create has to work for their movement in and out. It is a real challenge. Set design, in the way I approach it, is about compromise and facility, making sure that it works but making sure that my vision, my identity, my fingerprint or footprint, emerges as part of the overall concept.

NGN: You have worked at the Public Theater, where you had a predominantly White audience, and at the New Lafayette Theatre, where you had a predominantly Black audience. When you designed a set, what role did the makeup of the audience play in the production design?

AO: I don’t design for a Black or White audience. I just design for audiences. I don’t particularly cater or favor any particular ethnic group; however, all of the set designs that I have done have had an origin in Africa, in the sense that all the playwrights have been African or African Americans. The audience is very important, but I don’t particularly differentiate what the ethnicity of the audience is.

NGN: Could you talk a bit about the budgets you have had as a set designer and how long did you typically have to come up with a set?

AO: [Laughs loudly.] Well, let me put it this way: The New Lafayette Theatre was a unique experience for all of us who worked there. Bob Macbeth, who is a brilliant director, was able to convince the funding sources, specifically the Ford Foundation, to come up with a large sum of money, unprecedented during that period. When I worked with the New Lafayette, which, again, was a profound life-altering experience for everyone who was there, we had a budget. For the first time, for many of us in our careers, we all had a salary—we had a steady paycheck every two weeks. The key, in terms of my set design, was that I had the budget to buy the material for all of the lofty ideas I had about what a set should be. I think because of that I was able to create some really powerful sets. I never had to worry about the budget at the New Lafayette, but when I got to the New Federal Theatre a lot of times it was pretty bare bones. I found myself really having to improvise. I had to repurpose some materials from other sets, but I was still able to accomplish what I envisioned. Again, because I didn’t look to design the set in a traditional sense, I was able to use geometry, planes, color, shape, always being able to facilitate the needs of the actors and the purpose of the playwright and the directions of the director. The experience with the New Federal Theatre was wonderful and I had a profound experience. I did four productions for them between 2006 and 2014.

NGN: You were of the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s and 1970s, and you were among the founders of the Weusi Artist Collective, whose philosophical foundation was to honor the aesthetic principles that supported Afrocentric or African American culture. How did the Weusi Artist Collective come about?

AO: They started out as the Twentieth Century Creators in 1964, headed by James Sneed, who years later was the resident artist of the National Black Theatre and changed his name to Jemisi Obanjoko. The Twentieth Century Creators was a gathering of artists from the tri-state area: New Jersey, Connecticut, and New York. We came together to do the first annual outdoor art festival along Seventh Avenue. That was a mind-blowing experience for the community, because previously, we were well known for our dance and our theatricals, but we were not known in the community for the visual arts in any real sense. People in that community would buy reproductions of landscapes from the five-and-dime stores; a lot of our people had a picture of a White Jesus in the home. The street fair was really the first major outdoor festival that Harlem had ever seen. We brought all of these Black images, African images and designs, and we placed this work on the fences, running from 127th Street all the way to 131st Street, all along what is now Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, which was Seventh Avenue at the time. The experience that our people expressed was just so gratifying. They had never seen images of themselves portrayed in the way that the artists were able to portray them: regally, the natural beauty of color, the design that was very much a part of the inner spirit. The community, their minds were blown. And then, in 1965, there was a philosophical breech between James Sneed and a group of us who did not support his mission to integrate the work into the mainstream institutions, which, at that time, was alien to our objectives. Later in life, I realized he was doing what needed to be done, but at that point we saw it as not necessary or even wise to satisfy the Metropolitan Museum and those other mainstream museums. There was no Studio Museum in Harlem at that point; we did not know of any real Black museums. We rebelled and split off into a group: Otto Neals, Taiwo DuVall, Abdullah Aziz, Gaylord Hassan, Abdul Rahman, Ronald Pyatt, Perry Cannon, and me, then later Dindga McCannon, who joined us as a teenager. We splintered off into the Weusi and began to meet on 139th Street. After we did the second outdoor art festival in 1965, we moved the show from Seventh Avenue to St. Nicholas Park and that continued on for about a decade, right up into the mid to late 1970s. Then five members of the Weusi (Otto Neals, G. Falcon Beazer, Taiwo DuVall, Abdullah Aziz) split off and formed their own group. They saw a need to control where their works were shown and could not wait once a year to do the outdoor art festival. They rented a space and had the cooperation of the landlord to rebuild the first floor into the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Art Gallery. And then those of us who did not buy into that first group joined, I being one of the later members coming into Nyumba Ya Sanaa.

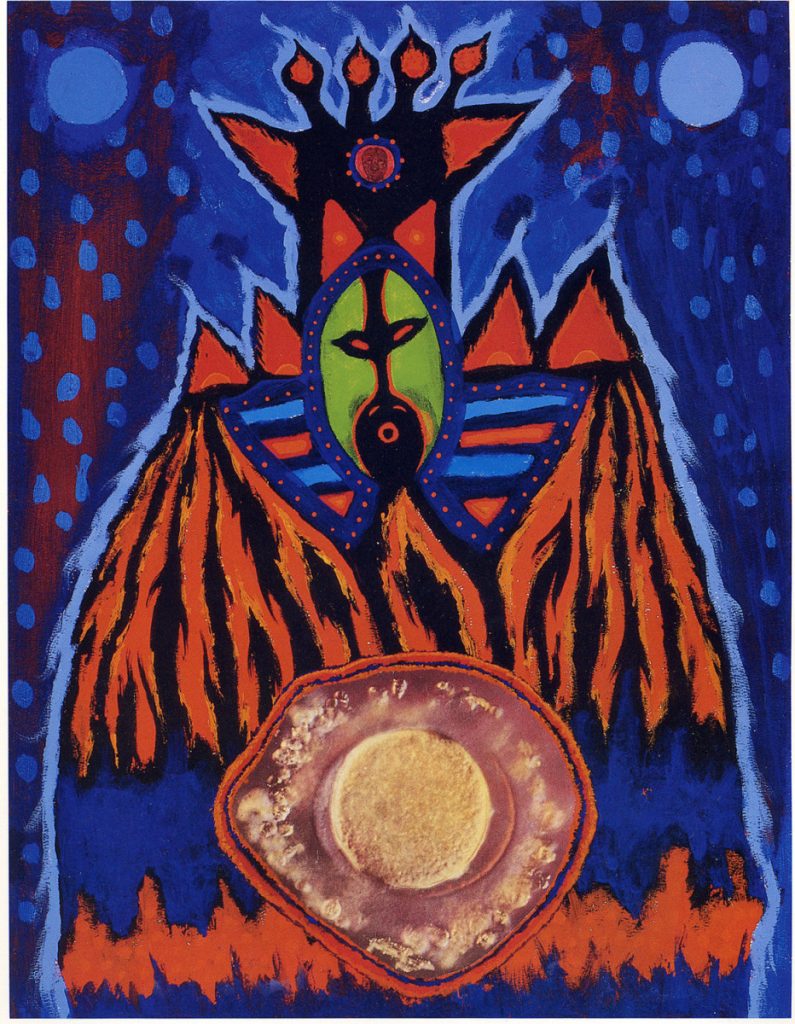

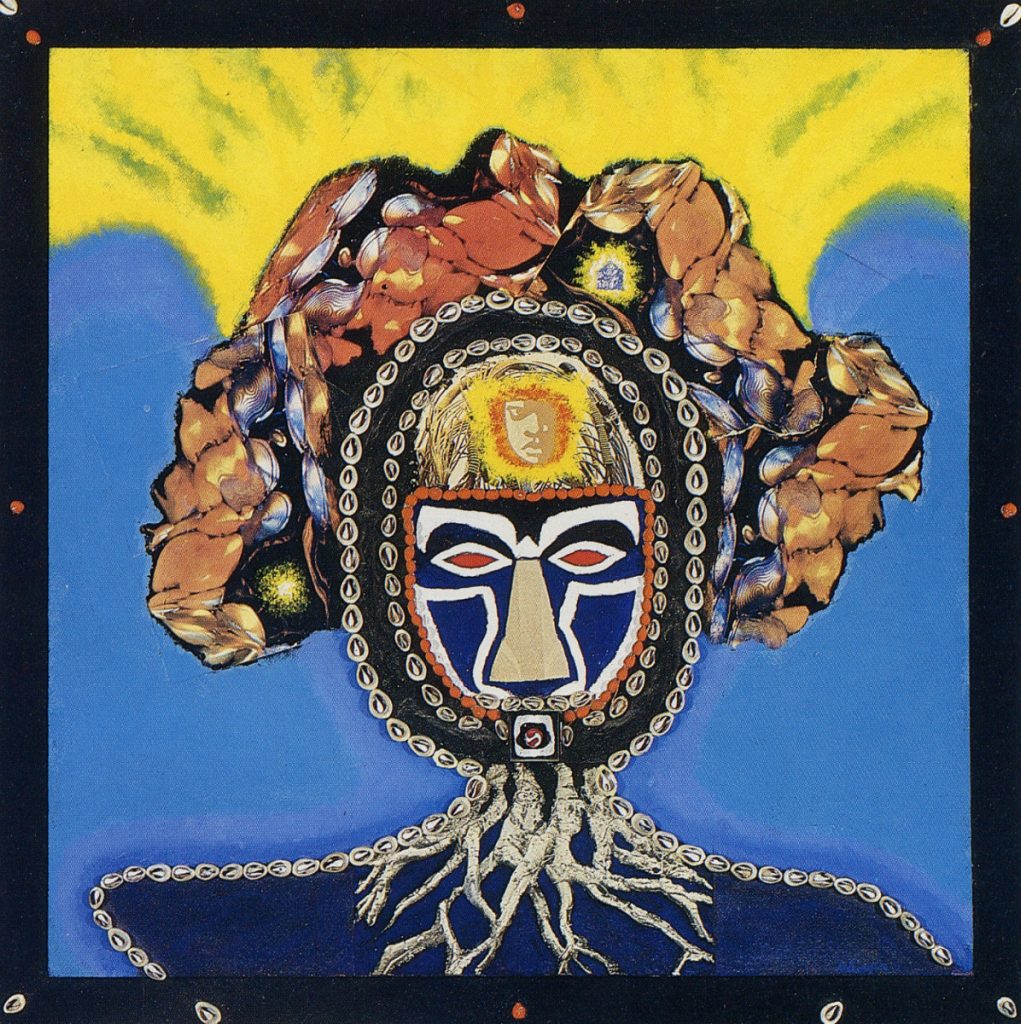

From left: Emerging Spirit, 1969; Pharaoh, 1973; The Prophecy (detail), 1969 — a mixed media piece that was used as part of the environmental set in the 1970 New Lafayette Theatre production of the futuristic play To Raise the Dead and Foretell the Future.

NGN: Can you talk a bit more about the Weusi artists and their overall contributions to the politics of the Black Arts Movement?

AO: We believed we had the responsibility to transform, or destroy, a lot of derog-atory images that were put upon our people from enslavement days. Our mission was to create an art that was independent of European aesthetics, one that exemplified excellence and portrayed much of our positive, constructive history and contributions to the world. And at the same time it was to make sure the art was good art, in all its aspects: composition, color, form. We were showing a whole new aspect of who we were as a people to the world. That was our mission. We were the first to exhibit Faith Ringgold in Harlem, at the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery, which served as a tremendous showcase for many people. Before AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) was even formed, we showed Frank Smith and James Phillips, who later became an AfriCOBRA member. We were pioneers, not only in that this was the first major gallery, but that we were kind of an incubator. People such as Olatunji, Amiri Baraka, and Larry Neal, all of them flowed through the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery. The Weusi artists, in a sense, looked at ourselves as the visual component of the Black Revolution or Evolutionary Movement. Our philosophy of connecting with Africa was paramount. Many Africans used to come to the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery. We had a reputation of being this Black Mecca of culture in the Harlem community at 158 West 132nd Street.

NGN: The National Black Theatre hosted an exhibition for the Weusi artists. What would you like to share about this experience?

AO: Barbara Ann Teer [the founder of the National Black Theatre] was a real supporter of the Weusi. I will never forget, one evening I was driving across 125th Street, and there were all these fire engines. I got out of my car, and Barbara Ann Teer and I watched the National Black Theatre burn down. We stood there and watched. We both pledged at that point, I will never forget, we said, “The theater will rise like a phoenix.” In the years after that, Barbara went through living hell trying to rebuild a theater, to a large degree because she had to get the support of politicians. She was quite charismatic and was able to, with the support of the community, raise the money to rebuild a theater in its present state. The Weusi looked at the New Lafayette Theatre, the National Black Theatre, Ernie McClintock’s Afro-American Studio for Acting and Speech, and Roger Furman’s New Heritage Theatre Group all as partners in the struggle and the perpetuation of uplifting our people through the arts.

NGN: Abdul Rahman, who was a committed member of the Weusi Artist Collective, was also a major set designer during the Black Arts Movement phase. He did designs for James Baldwin’s Amen Corner; Langston Hughes’s Simply Heaven; The Water Witch for the Harlem Children’s Theatre; Cynthia Belgrave’s The Wedding; Ed Bullins’s Has No Choice; and Adrienne Kennedy’s Beast Story. He was also commissioned to do a mural for the New Lafayette Theatre. What more can you share about Abdul Rahman?

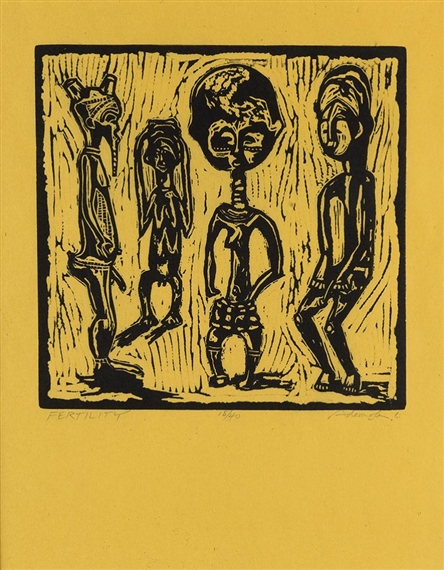

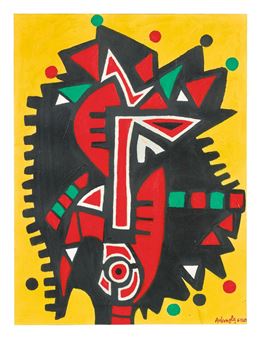

From Left: Fertility, 1968; As Above, So Below, 1983; Untitled, 1969.

AO: He did those sets at the National Arts Consortium, which came out of an alliance between the Weusi and Hazel Bryant, who was a great theater person and founder of the Richard Allen Center for Culture and Art. And because Hazel was a genius, and just a very entrepreneurial and charismatic person who was able to raise money, we [the National Arts Consortium] were able to lease an abandoned garage on Sixty-Second Street, right across from Lincoln Center. I remember fondly how we rolled up our sleeves, put on our jeans and construction boots, and transformed a greasy, former garage into a theater and a gallery. It was basically the Weusi personnel who got in there and built the Richard Allen Cultural Center in an abandoned garage. It was there that we produced Amen Corner and some of the other plays that you mentioned. Rahman was the set designer for those productions at the Consortium, but the Weusi artists helped him build those sets. And it was Hazel and the Weusi who produced and created the first Black Theatre Festival at Lincoln Center, around 1970 or 1971.

NGN: William Howell, who was a member of the Weusi Nyumba Ya Sanaa Art Gallery, died when he was only thirty-two. He was also the art director of New Lafayette Theatre. What would you like to share about Mr. Howell?

AO: Brilliant graphic designer. He helped produce some of the most phenomenal posters. That was one of the exemplary things that the New Lafayette did. We produced six Black theater magazines over the years. I was directly involved with three; Bill Howell was involved with at least two of those before he passed away. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Bill’s New Lafayette posters, but they’re really worth looking into. If you go to the Schomburg Center, the posters are among my career papers. Bill designed To Raise the Dead and Foretell the Future, Goin’ a Buffalo, The Devil Catchers, A Ritual to Bind Together and Strengthen Black People so that They Can Survive the Long Struggle that Is to Come, and others— all wonderful designs. Bill founded the first Black gallery, Pamoja Gallery, right there in the middle of Greenwich Village, maybe in 1969 or 1970. One of its patrons was Pat Evans, who was one of the first Black women to wear her hair bald and who became the face of Black fashion. Bill formed Pamoja in the spirit of the Weusi, and we looked at it as our downtown branch. We all loved Bill.

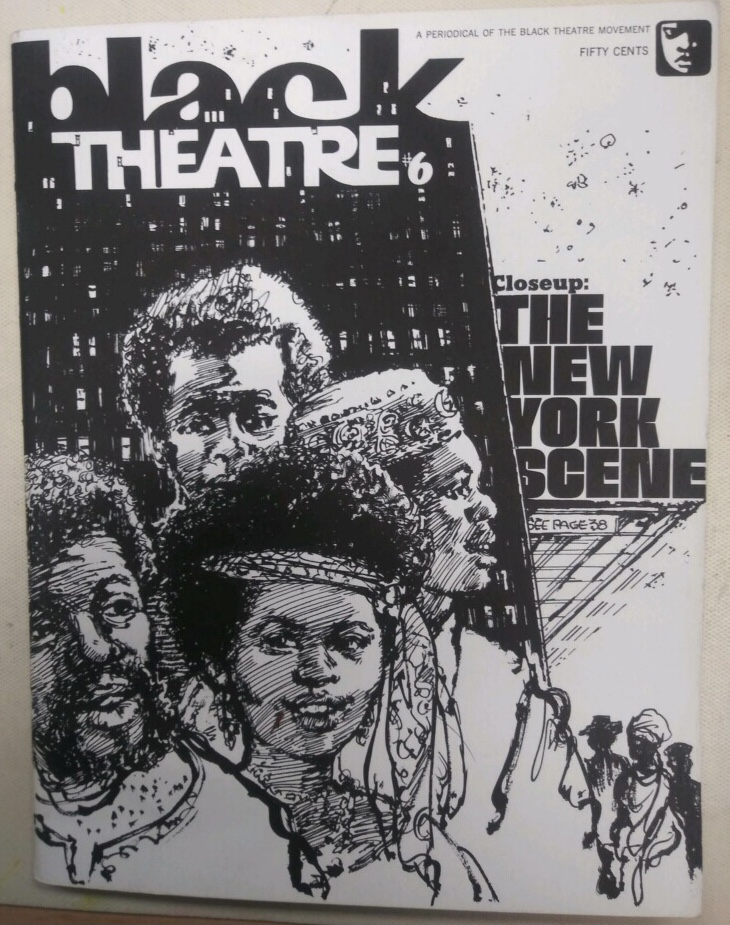

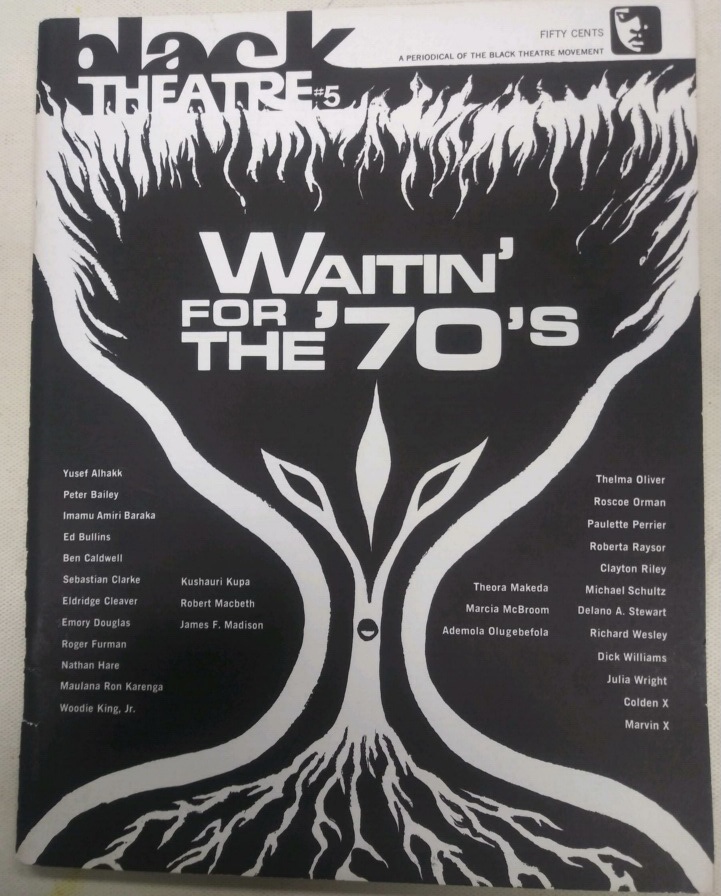

Two Black Theatre magazine covers.

NGN: You were resident designer and art director for the New Lafayette Theatre. Were you involved when it opened under Robert Macbeth in 1968?

AO: I was there for the fourth production, which was A Ritual to Bind. They had done In the Wine Time, Who’s Got His Own, and We Righteous Bombers, their first three productions, before they invited me up. Bob had this idea to do A Ritual, to do something different than the traditional theater, and he invited me up and that is how the partnership began.

NGN: You were also associated with the Public Theater. What did you do there?

AO: My experience with the Public Theater was through Black Visions, which was quite a production, choreographed by Hope Clarke and directed by Novella Nelson. This was a major breakthrough for them because Novella Nelson directed Sonia Sanchez’s Sister Son/ji. We did a production of four one-act plays: one by Sonia Sanchez, two by Neil Harris, and Getting It Together by Richard Wesley. Thereafter, I interacted with them on an informal basis, with some of the Black productions and Joe Papp. This was my major involvement with the Public Theater.

NGN: Edvard Munch, the Norwegian painter, did set designs for many of Ibsen’s plays. Andy Warhol worked with Theatre 12 Company, and Jasper Johns did sets and costumes for theater. Isamu Noguchi did sets for Martha Graham’s dance company. Picasso also did some stage designs. During this Black Arts Movement, you had so many Black visual artists who did set designs for theater. If not set design, they were actively involved in theater. You, Romare Bearden, Roberta Raysor, William Howell, Abdul Rahman. Even Emmett Wigglesworth designed costumes and sets for the Black Spectrum Theatre in Queens. Wigglesworth also wrote and directed plays for CORE Freedom Theater in San Francisco. I know Roberta Raysor worked as an actor and set designer for the New Lafayette Theatre on various productions. Can you talk a bit more about the work of Black visual artists as designers for theater? More specifically, who were some of the other visual artists from the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s–1970s you were aware of who worked as set or costume designers?

AO: I didn’t know many of them so I’m learning as you mentioned these names. I remember Bill [Howell], who was more graphic design than anything, helping me with the design of the set on The Ritual to Bind. When we did To Raise the Dead and Foretell the Future, I did an eight- or nine-foot disc that was suspended from the ceiling of the theater. The disc was painted with certain iridescent paints and under different lighting, it would change total identity. For one, you put a black light on it, and you got the feeling you were in outer space. You put another light on it and it would look like you were in the middle of a solar system. Even though I was responsible for the overall design of the set, Bill helped me paint it. With his talent and skill, he was a display artist, too, and would build commercial displays.

NGN: What can you share about Ed Bullins? I know you did the graphic for his first novel, The Reluctant Rapist—

AO: I did about four or five of the covers for Ed Bullins. I did the cover for The Reluctant Rapist, Four Dynamite Plays, The Theme Is Blackness, and The Duplex. I did all the sets for Ed Bullins’s plays at the New Lafayette Theatre. This was a real challenge for me. The first piece I did when I joined the Lafayette was this very spiritual momentous tribute to the ancestors [A Ritual to Bind]. It was so spiritual in part because the day when the play opened there was actually a solar eclipse. We were all surprised. So, in celebration of that, we were all asked to shave our heads. That was the first time I ever shaved my head. Then, after we did the spiritual awakening play—which Ed wrote in collaboration with Macbeth, so all the ritual was a collaborative writing for them—Bob Macbeth then chose to do this play Goin’ a Buffalo. I had a real problem. I laugh about it in retrospect. I had absorbed myself into the spiritual uplift and all of that and then he was asking me to do this play about a pimp, because that’s what Goin’ a Buffalo was about. I laugh now because I said, “Hey, man, I can’t do this; I thought the theater was headed in this spiritual direction.” Bob said, “No, we’re not going to get caught up in that, we’re reflecting on all aspects of our people. We did that with the spiritual death of our people, now there’s this other side about people.” So, that was a profound experience. And how I handled that was to paint the stage in a giant checkerboard. After we did that play about the pimp and that life, we went back to the spiritual and did To Raise the Dead and Foretell the Future, which featured the painted disc I mentioned earlier. It was a profound experience working with Ed Bullins. His range was phenomenal and having to adjust from play to play was quite a challenge, but it was an exhilarating experience.

Ademola Olugebefola with playwright and author Ed Bullins.

NGN: In 1969, Benny Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) to protest the Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. No Blacks were involved in organizing the exhibition. So BECC, Spiral and the Harlem Cultural Council, and the artists’ group Weusi, the group you co-founded, joined forces—

AO: To protest.

NGN: Yes, and picketed the exhibition as separate groups. What did all of that mean to you and the others?

Ao: We were highly offended with the fact that they would organize an exhibition talking about Harlem that did not include any curators, designers, or anyone of color putting this exhibition together. So, we did protest and raise all kinds of noise about it, and eventually, they made a whole lot of adjustments in organizing that exhibition. I had a great relationship with Benny before he passed away. I had a great admiration for him and his ability to deal with the mainstream art world but still keep his integrity. We had to be part of those museums and we had to be represented properly. So, of course, we joined together to picket the museum and put pressure on them. The Harlem Cultural Council was very instrumental in that. It was headed by a woman named Jeanne Faulkner who happened to be a great administrator, and Ed Taylor; both of them were opera singers. They really were at the core of the Harlem Cultural Council. Bearden was one of the board members of the Harlem Cultural Council as well. In those days we had no problems getting together, in many instances, around causes. We looked at ourselves as a mother and sister organization; rallying around Harlem on My Mind was the proper thing to do. We believed in unity and with unity we had power. A few years later, we had a similar situation with the Whitney Museum, when they tried to organize the show Contemporary Black Artists in America. Benny was involved with that as well, but that is a whole other story.

NGN: There is no doubt about visual literacy, but do you think there is such a thing as visual political literacy, where the politics must be represented in the visual makeup of a production?

AO: Well, I guess you can look at it that way. During the 1960s and the 1970s, there was a great dialogue—disagreement to a large degree—because there was a tendency by critics to try to label all art coming out of the Black experience as protest art if it wasn’t abstract. Some of it was true, in the sense that some of the images were very much in the frame of protest, raising the consciousness, with political overtones. For instance, I did a piece that became quite popular, called Confrontation. It was a direct statement about the clash of African American values and culture against the White supremacy attitude. And a lot of my colleagues in the Weusi painted images that spoke to the political confrontation between the mainstream political machinery and our people; Abdul Rahman’s piece called Bottom of the Barrel was a tremendous statement. Gaylord Hassan, who regrettably passed away recently, did political paintings, and a lot of Emmett’s work had political overtones. So, the Weusi, in terms of actual representative images, spoke to the political environment. But then the critics and the people in academia tended to want to label everything coming out of the Black experience as political. They wanted to use that as an excuse, in many instances, to deny access and recognition in the mainstream art industry. So to me it was a double-edged sword in terms of trying to make progress, or make a living, or be respected and accepted in American visual arts.

NGN: The Black Arts Movement period was a phase when many artists promoted a Black aesthetic that was closely connected to an African heritage, as well as promoting the notion of using art as an instrument for social change and for Black racial progress. You were on the frontline of engagement with Black arts and the Black Power Movement. How did this play a role in your art?

AO: Many of us felt it was a responsibility that we create images that spoke to uplift, enlightenment, even the defiance of the normal, for the most part, which would have us within an enslavement mentality. Many of my early images spoke to rebellion, Black power, Black enlightenment, all the time also recognizing that you still had to create good art. If you look at some of my images from the early part of my career, you will see that I worked a lot in the woodcut medium, because woodcut and lithograph were able to be reproduced. Part of the philosophy was to create images that would not just be one piece hanging on the wall in a museum, but something that could be distributed widely, specifically to our people, but also to the rest of the world. That was part of the strategy.

NGN: How has your art changed from the mid-1960s?

AO: I don’t know if it has changed so much, because I have always been interested in color and forms and abstract art—all the excitement of modern art, of contemporary art. But during those pilot stages of my career, in the Black Arts Movement, I didn’t feel I had the luxury to just express myself through color and forms. I felt I had a responsibility to create images first that our people, specifically, could recognize readily. In my art today, I have more leeway working in abstraction. For instance, I am working on a piece right now which is trying to interpret music through color and form—visible music; I am calling it On Green Dolphin Street. It is a tribute to Bill Saxton, a brilliant saxophonist, composer, and musician. He owns a club on 133rd Street called Bill’s Place, which seats about thirty-five or forty people. And every Friday and Saturday, for the last fourteen years, he has these sessions, and he gets a lot of people to come up; he is on the tourist route. All I am saying, in essence, is that my art has not changed: I am still doing a lot of figurative work, especially my drawings, but in my painting and mixed media work I’m doing more color work. How do you reach past the frontal lobe of the mind, so that you can invigorate those same audio sensors through the visual equation? That has been a quest of mine for years. I have not succeeded totally yet but I am still on the quest.

New American Landscape Series, 2007, courtesy of the Kreiger Creative Group.

NGN: Today, there is also an important level of activism from Black artists connected to politics; Black Lives Matter and particularly the murder of George Floyd have fueled Black artists to look at and interpret the times through the politics. Is there a connection between what you Black artists did during the 1960s and 1970s and what is happening now with Black artists?

AO: We are all essentially coming from the same place. One difference might be that we formed an Artists Collective. The Weusi established Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery and Academy, which then allowed a degree of self-sustaining independence to collectively tackle the task of creating images that reflected and depicted the ongoing historic brutality and injustice without the broad exposure now available through social media platforms. Today, there are generally more outlets available through mainstream channels. My generation also had to virtually educate our people en masse to look seriously at fine art, and our artistic mission was to promote elevated imagery of ancient African kings and queens, warriors, scientists, doctors, educators, et al., while simultaneously dismantling and replacing antebellum-era negative stereotypes in the public sphere (mass media images and branded consumer products, e.g., Black Sambo, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, the racist promotion of cartoonish grotesque distortions of our natural features).

NGN: How would you sum up your achievements as an artist?

Ao: I have been fortunate among my peers to have gotten a fair amount of exposure. I have created some iconic images that have become well known, and have been fortunate to do some large-scale works that virtually hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people, have seen. I have standing works even now; for instance, one piece I did called Harlem Village Odyssey, a twenty-eight-by-eight-foot mural, is in Banco Popular on 125th Street. Another mural was up for twelve or thirteen years across from the high school on St. Nicholas Avenue. My work is in collections such as the Studio Museum of Harlem, and the Schomburg has my career papers. I feel I have made a reasonable impact and reached a fair level of success, in terms of recognition, being published, having that phenomenal theater experience, and having been part of a founding team of this very institution right here, the Dwyer Cultural Center. I have made an impact, but I still have a way to go. I am still questing for broader exposure, broader recognition, and broader financial success.

NGN: Is there anything you’ve wanted to do as an artist that you did not do?

AO: I have always loved the idea of architecture, and I would like, before my transition, to do even larger things than what I have done. The largest mural I have done is forty-eight feet high by twenty-eight feet wide. I want to actually do huge structures that when you walk in or go through them you come out transformed. I want to do building-size sets and sculptures that can transform the consciousness of someone who enters or witnesses these pieces. That to me is my ultimate goal. I also want to work more in light; I did several light pieces about ten years ago. That is another thing I would like to do in terms of the evolution of my work; that’s going forward.

NGN: What have you learned about functioning in the art world as a multitalented Black artist?

AO: Interesting that you ask that question. One of the things about the arts industry—which, by the way, is a multibillion-dollar industry—was a tendency, which I think may have expanded by now, to want you to stick with one style or one design and have that be your signature. I could never subscribe to that. I like all the mediums; they are challenges and forms of expression. My etchings are quite different from my woodcuts; my multimedia work is quite different from my constructions. That has been my experience and I may have even paid a price for it because I never fit into one box. It is just now, at this stage of my advanced career, that people recognize I do a number of different things well.

NGN: What wisdom would you share with an emerging Ademola Olugebefola?

AO: I would share with an emerging artist three things. One: You have to decide that this is what you really want to dedicate your life to, there is no half-stepping. Two: Always, always strive for excellence without being so rigid that you have tunnel vision—in a sense that you can’t see other kinds of forms or styles. Keep your mind open. Three: Do not, at any time, compromise your integrity. Whatever your vision is, whatever your alliance to righteousness, or doing the right thing is, do not compromise your integrity or your vision.

NGN: I thank you very much and I do appreciate this, Mr. Olugebefola.

AO: It has been a pleasure.