You have the psychological or subjective moment of the father problem.

This affects all of society. . . . The absence of the father is a typical German problem.

That is the reason for such agitation, why it has such a disquieting effect.

—Gerhard Richter (MoMA catalogue, 2002)

fter my mother’s death, I cleaned out my parents’ house in Maryland, sold it, sold their things too, put whatever was not sold into storage centers, here and there, a little bit everywhere.

My father’s artwork was stored in the house and I treated it the same way, sent it to a part-time dealer in California, and asked him to put it on eBay. I thought it would be enough to intrigue the public with some details. My father was German, a painter. He came to America in 1937. He was an immigrant, fleeing an autocracy.

A friend intervened: was I mad? Selling it online was like throwing it away. I retrieved my horde. I began to take stock. I showed some paintings to a few more friends. Each had a hand in sorting through the snips and bits of the past, turning them into something that could be shown, a collection with a history, with an inventory, with something that took it out of bulk and confusion, into the light of things that had a sense and were freighted with quality and purpose.

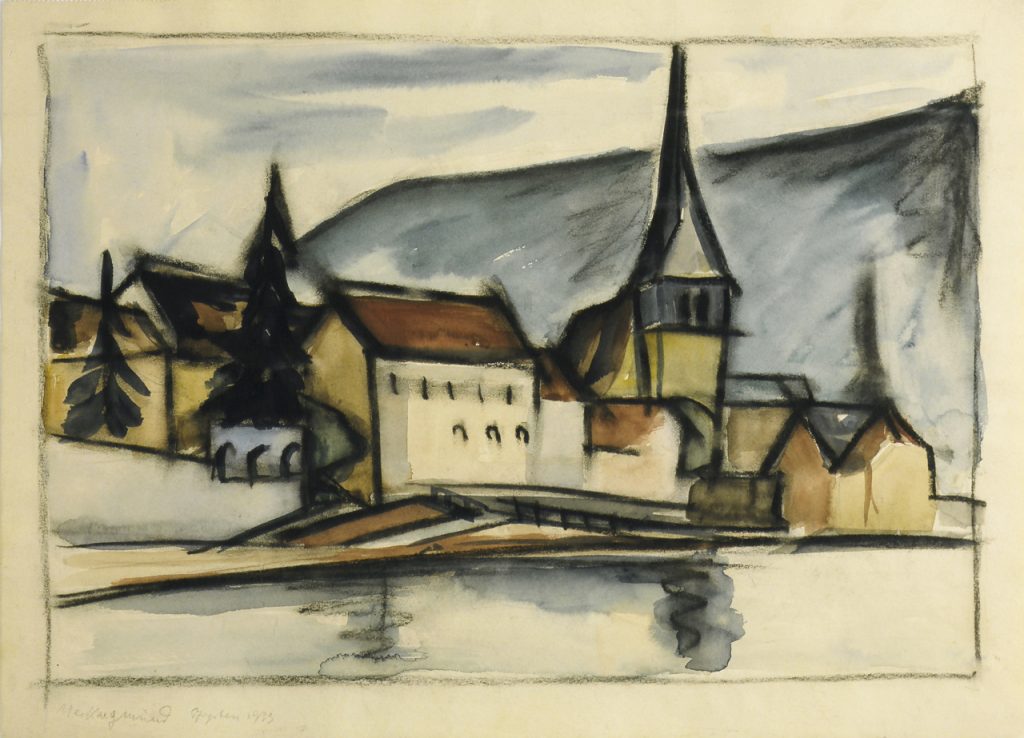

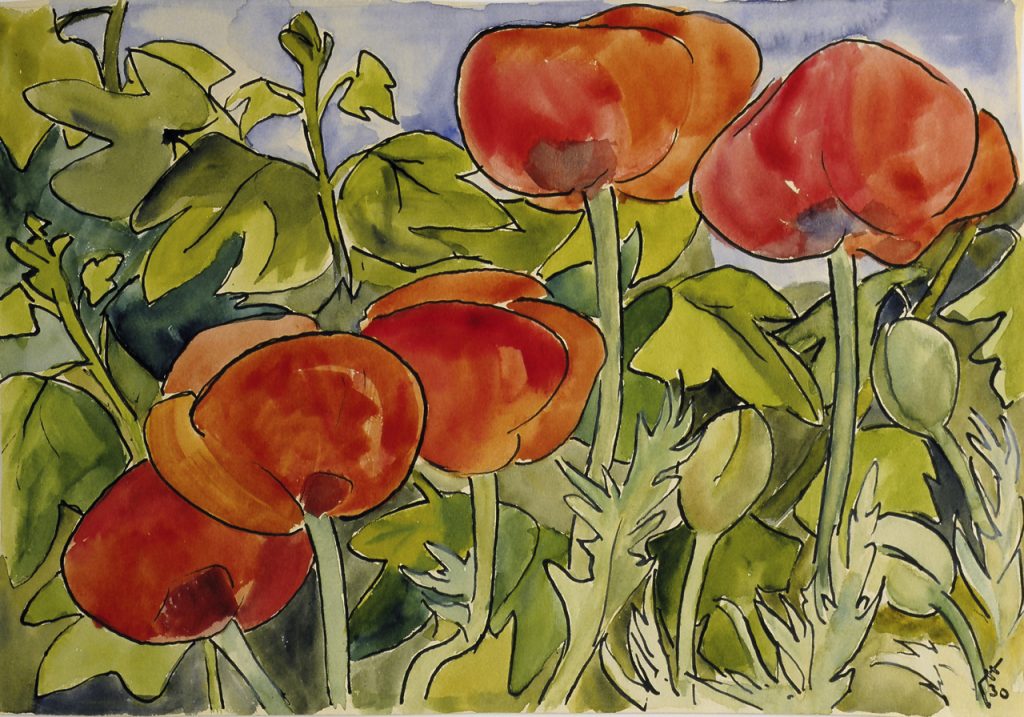

Finally, to interest people in my father’s work, I had an attractive pamphlet made. A nude was reproduced on the cover of the little book and it spoke for the man’s graphic talent, for the way Max Beckmann must have influenced him, spoke to his youth, to his reckless devotion to the emotion of a chalk stroke and the tension a line could bring to paper—the way a stroke of lightning brings tension to the sky. Inside the pamphlet other works impressed with the way he worked his charcoal and his brushes to capture the sway of light and the dance of the dark. In one painting dated 1928the sunshine reflects off the water, bounces off it like a high note in a cadenza, and then off a shipside, a dock, calling attention to the shadow shapes and patches of brilliance which never leave the Schleswig-Holstein landscape alone. In another watercolor, a field of poppies is examined from below, the heads of the poppies floating over the paper like balloons, like hallucinations, like red clouds, full of hope and promise.

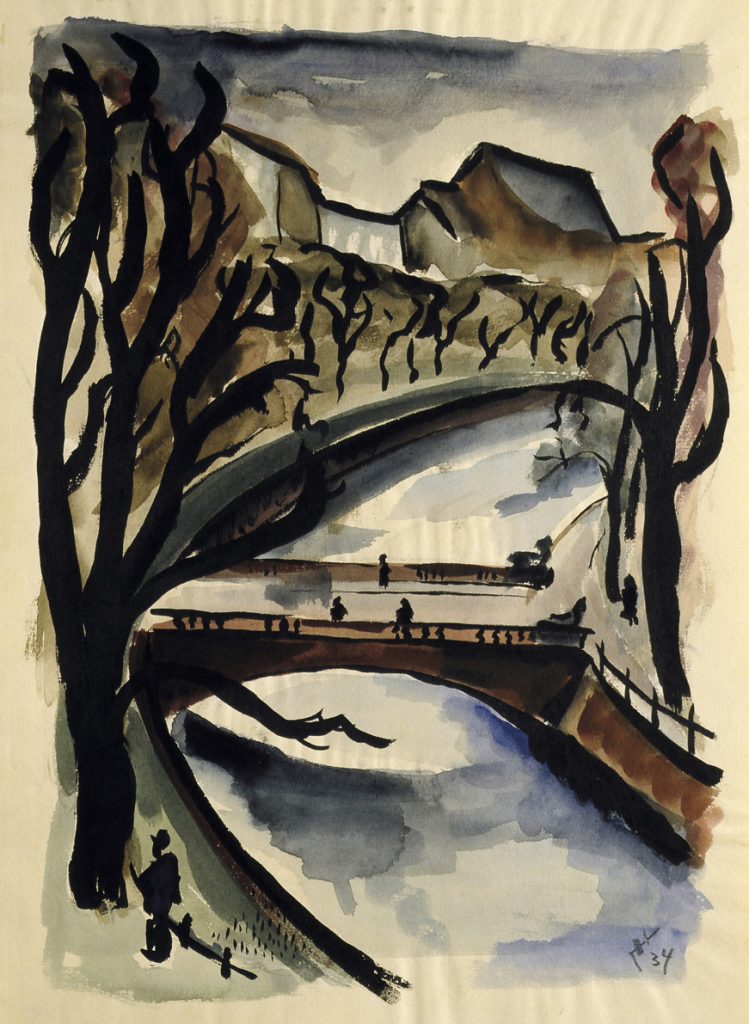

His brush was his guide. Wherever he found himself, he used it to pull back the light as though it were dust that he could brush away to uncover something even lighter—in the twenties—or something even darker—afterwards. There was an opulence to the early work, a swollen expectation in the trees and the church steeples. But as time went on you could see it grow tighter, darker, turning inward. By 1932the structure of each work stood out painfully, as though to resist the coming storm. A landscape with a bridge and the date 1933was dark and twisted, village streets had tightened, roofs pitched forward toward the coming folly. Turn the paintings upside down, and one discovered a composition so sure, they worked just as well. Maybe they worked better. Maybe the artist was turned upside down too while the storm left nothing behind, terrifying his mother, expelling his brother (whose wife was Jewish), leaving my father to wander, a solitary man.

♦

A time passed. I took steps. I live in Paris and met an art critic from Le Monde. He looked at scans and assured me, over and over again. Yes, the work had “something.” I had complete records made, and began to worry about protecting it all, about conservation and storage. A few pieces even disappeared. Had they been stolen? This added to the aura of my secret collection. I went to Kiel, north of Hamburg, in Schleswig-Holstein, where I knew my father had been to school. At the Faculty of Fine Arts, they told me there had been no studio courses in the twenties: but the work looked good—solid, strong, and typical for the period. Heinz Emil Salloch must have been at the Muthesius-Hochschule, an art and architecture school, just down the hill.

As it turned out, school records from the studio courses at the Muthesiushochschule had been systematically destroyed by the Nazis in ’33 (the school was considered very left-wing) and whatever else was left had been obliterated by allied bombing in ’44. A long investigative process began. Iris Mielke, a recent graduate of the design department, discovered places my father had lived, Albertstrasse 23, Adolphstrasse 15. It was easy to imagine the old man as a young man, imagine him in Kiel, a bowl of gruel, a slice of Sültze for breakfast, his collar up, portfolio under his arm, going down to the docks to paint. But had he really attended master classes at the Hochschule? The work always settled the issue. If he lived in Kiel, if he did these paintings, he had been to the Hochschule.

Together we went to the Ostholstein-Museum. Iris’s proposal to build flexible exhibition architecture for the museum had won the Muthesiushochschule first prize the year before. She and the director of the museum, Dr. Klaus-Dieter Hahn, were on good terms. Dr. Hahn looked at the book of scans, and then at me:

“Yes, I agree, Es hat etwas Besonderes—there’s something special here. I can give you a show in two years.”

The work had been hidden in sea chests for seventy years. Rarely had anyone even bothered to unwrap the drawings, the fragile pastels. Now it was all about to become visible. It would all stand on its own, hang in the light.

♦

Chinatown, Canal Street, Manhattan, was the first stop on the return trip for Heinz Emil Salloch’s work. I had taken the paintings out of storage, rewrapped them carefully, each in its transparent plastic folder. Now I needed a suitcase. I went from shop to shop until I found a gray Samsonite monster equipped with wheels. It could have been a medium-sized refrigerator. I didn’t like it. But I didn’t have a choice. Empty, the Samonsite made an enormous racket. Distinguished Chinese gentlemen turned to watch me walk by, small Chinese women lowered their eyes in embarrassment. Children ran around me, beating on the suitcase as they passed as if it were a drum.

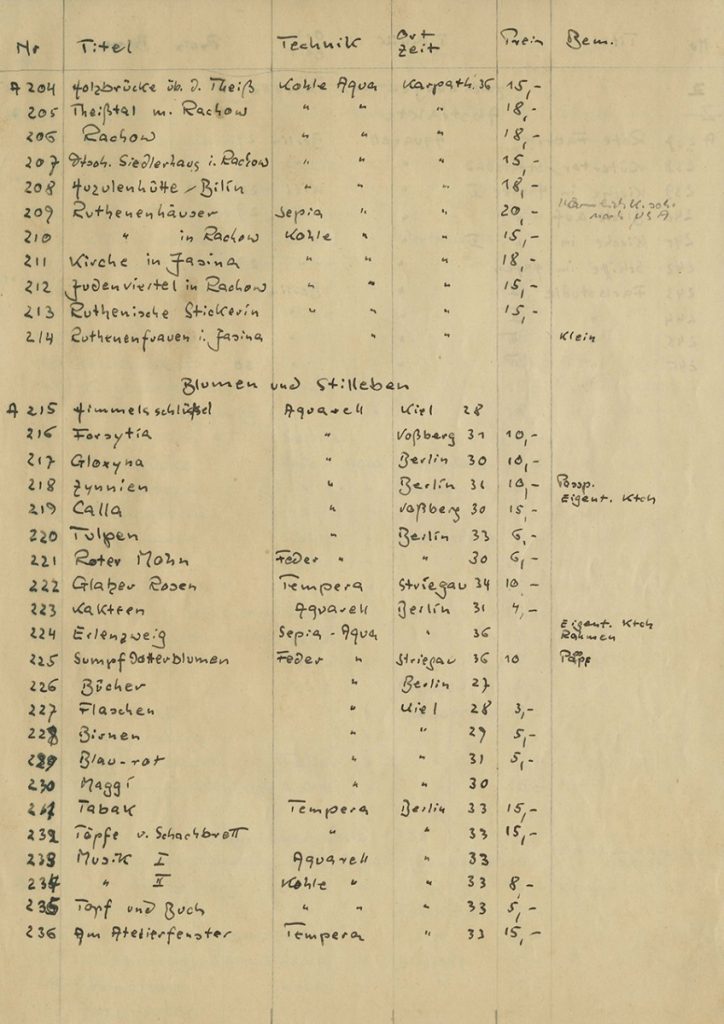

There are no photographs. There is no diary. The man himself was silent. Only a logbook accounts for wanderings and production. That he took himself seriously as a painter is not in doubt: every scrap of paper was annotated. Medium: place: size: price. In his neat hand we go from Berlin to Kiel to Lübeck to Winterthur to Wustrow to the Sudetenland. We go from 1928to 1937. The only other personal item he left behind from that period before the war was a sketchbook called “Summer on Long Island.” It is a book in the form of a letter, which accompanies a series of twelve modest watercolors, each with an accompanying note, the whole addressed to his mother whom he left behind in Berlin in 1938. For the book still to be in his hands, it must have been very important for both of them. He had to send it. She had to receive it, keep it safely in Berlin, throughout the war, and throughout the Russian occupation, words that are worth repeating: safely in Berlin, throughout the war, and throughout the Russian occupation.Then she had to bring it with her to America.

When I filled the gray elephant with paintings and drawings, the noise abated, perhaps out of deference to the contents. Still, it was hard to negotiate in SoHo, where I was living at the time, holding the elevator door open while I hauled the suitcase forward, hoisting it up into the back of the taxicab. How long was the road and what would I find at the end? I didn’t know. Each little link on the chain would provide the impetus for the next little link, and each would find its own place in the expanding puzzle. I went through customs and immigration, along moving sidewalks, up and down escalators, into and out of more taxis.

“For my little Kate, Christmas 1938,” Heinz Emil Salloch wrote on the title page. An introduction followed: “This is not artwork, it is not even original sketches, since it was this fall that I copied them from watercolors I had done before. But for you I think it is a good reminder of the many other beautiful summers we shared together when we were happy.”

“Now imagine I am still sitting by your side and telling you about the pictures. But not much: because a ‘painter’ should paint. . . .” Den Maler soll malen.

♦

Close to the main train station, the hotel room in Hamburg was stark. There were no paintings on the walls; there was a yellow nylon bedspread; pink, threadbare towels hung limply off the racks in the bathroom. I was tired. Opposite, neon lights blinked, and down on the boulevard traffic was heavy. On the far sidewalk men and women hurried to catch the train for the Hamburg suburbs. Closer by, off to the left, some prostitutes plied their trade. They wore boots and short skirts, their knees were red, scuffed, older than the bodies they carried forward. They were young women, blond, pale, and white—probably from the East. I wondered what color Heinz Emil Salloch was for his German compatriots when he boarded the Luisenbergin Hamburg and sailed west in 1937? For most of them probably no color at all, invisible, a phantom already.

Professor David Galloway, critic and curator and good friend, had encouraged me with this project from the outset. Chance had brought us together in Hamburg and now he had finished going through the portfolio. He was impressed. He waited to gather his thoughts, announced that he would definitely write something. He would speak of the paintings, but he wanted to do more, he wanted to create something like a log of the journey, his journey, our journey, he said, more precisely. Perhaps everybody’s journey, he added, this time more obscurely. After all, hadn’t he been there from the beginning? Did I remember the café in Forcalquier, where we had first met, how hard it was to get the waiter’s attention, his remark when he had been through the slides: “This deserves a reputation.” Did I remember? Yes, very well. From coffee we had gone to wine, from wine into the evening. The road home was long. I could remember almost driving into a ditch in the last two kilometers. I felt extraordinarily tired.

The express trains that run between cities in Germany are called the Inter City Express, their acronym, ICE. The trains slip into the stations on time, breathe for a minute or two, and slip out again. Once again the station is empty, a cavernous greenhouse fit for monkeys and palm trees. But there were only Turkish sausage vendors, under improbable orange umbrellas, grilling bratwurst for famished travelers.

I waited with my suitcase at my feet until the express train to Berlin pulled in. Track 7, 13:42pm. I boarded only to discover that most of the seats were reserved. Couples sat with their heads on each other’s shoulders, exhausted from stages of a journey that must have brought them from Romania, to judge from the headscarf one woman was wearing and her husband’s shattered rubber running shoes. A once distinguished businessman and his wife did everything they could not to appear distraught because they had failed to reserve a place and all the seats side by side in this compartment were taken. Finally I found a place myself and left the mammoth valise in the aisle. I wanted to apologize, to explain why this beast was necessary to me, to account for myself, even imagined myself as a character in one of those novels of formation and apprenticeship that stud nineteenth-century German literature. My suitcase was clearly an irritation, my German was not up to my ambitions; instead I just slipped lower in my seat.

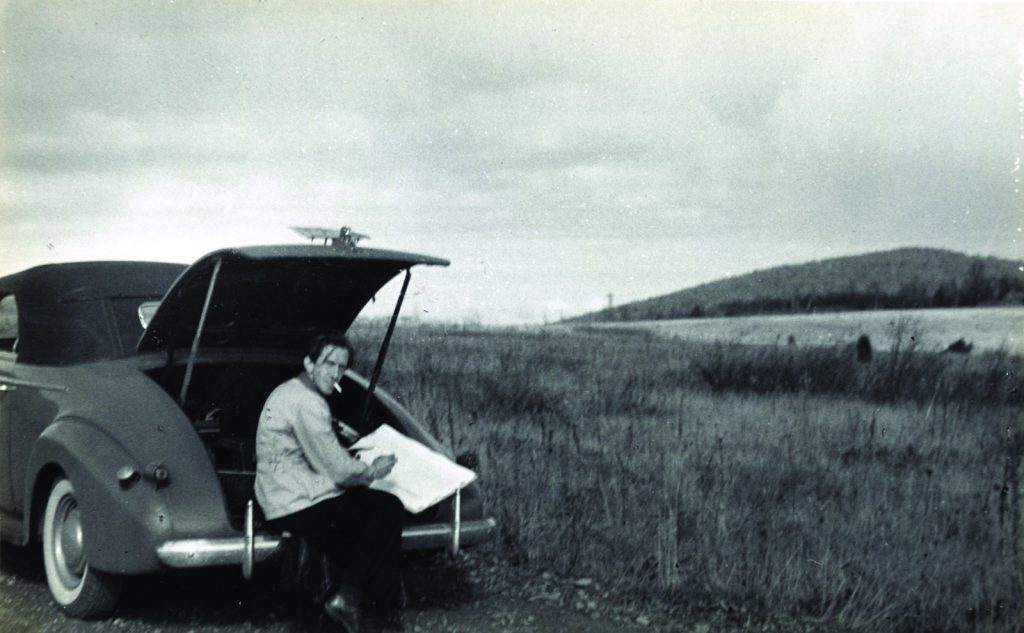

The train began to move out of the station and, very quickly, into the countryside. I thought of how Heinz Emil Salloch would have traveled in his time: mostly on foot. All he ever really wanted to do was get in close to some structure, or sit cross-legged for a while, up high, on a hilltop with a view over some village. I stared out the window. Already we were traveling at 250kilometers per hour through flatland, and then, between small garden plots that lined the intercity right of way.

In German the word for such garden plots is Lauben. Heinz Emil Salloch painted them in winter. Through the snow, the geometrical patterns of the fences around the Laubenin his watercolors seemed to be headed for the vanishing point, like people fleeing. If I shut my eyes, I believed I could see the dates on the two pieces of the collected works that came to mind, a watercolor of such a garden plot on a cold December afternoon, and its accompanying small drawing: 1933. When I opened my eyes, ICE and I were tearing through the outskirts of a vast industrial park. Old cranes, rusting warehouses, and abandoned cars made it look like installation art. If I shut my eyes again, I knew I could come up with several paintings that looked like the scene outside. Trucks passed, a bridge hovered in the distance. It looked like it might rain. What hope there was in my expedition had nothing to do with nostalgia. There is no hope in nostalgia.

I fell asleep. My foot dangled into the corridor. A woman in a hat with a pink bell-top and a synthetic pink fur coat woke me up and complained about my foot to her traveling companion. She said the presence of my foot in the corridor was “incomprehensible.” What would she have said had she known the gray mammoth was also mine? My view of things darkened, as though the train had passed from the landscapes painted by my father in 1929into a new era. 1933. What William Faulkner said about the American South seemed to apply here: “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.”

I dozed again and soon enough found myself in Berlin’s Ostbahnhof. I was staying with friends in Friedrichshain, in what used to be the eastern sector of the city. The taxi driver told me it was a short ride. We passed sections of the old legendary Berlin wall. They were covered with paintings and graffiti. It was hard to tell the difference. On second thought it was easy: painting obliterated the surface with color and meaning. Graffiti obliterated color and meaning with an anger that created its own wall. If Heinz Emil Salloch had gone on living in Germany, was that what he would have painted, walls becoming walls? Walls of marching men, of squadrons in black shirts? Did he think light anywhere else might still be like the light that had so inspired him, the soft glow of the Schleswig-Holstein countryside in the morning? Was he disappointed and disoriented when he came to America? Was that why he stopped painting oils? Why did he leave the oils in Germany? Maybe they were simply too heavy to carry with the other art, all of it works on paper. Maybe he sold them for 5dm and they are still hanging on some walls around Hamburg and Kiel, good pieces by an unknown Maler. What meaning his destiny gave to the word “missed,” as in wide of the mark, propelled forever into the indifferent cosmos. Could he imagine he might even be a father one day?

He wasn’t Jewish. He didn’t haveto go. Why did he leave, I was often asked?

He was unhappy: the Nazis didn’t like him. He got in trouble. . . . What was he? . . . A loner, a painter, a hard worker. A radical. . . . Are you doing this for him? . . . No, I am doing it for myself. . . . What does it bring you? . . . I will tell you when I have finished. When I have gotten them to the museum. When I have pulled this Samsonite mammoth on wheels across the lawn of the castle in Eutin and opened it for Dr. H. the museum director who looked at the scans and said, “Yes, they have something, I can give you two months for a show in three years.”

♦

Before my mother died I had published two stories about my father, “Nightrise” and “Romantic Landscape.” Each story represented my effort to come to grips with something that was haunting me about this man who, in spite of a lifetime together, I felt I barely knew, Heinz Emil Salloch, born December 31, 1907.

In “Nightrise,” my father’s slow descent into extreme ill health was described in minute detail. A man who had always been on time became a man outside of time. A man who hiked across Germany and who, according to his brother, once spoke of killing Hitler, became an invalid in a bed in the dining room. A man who was beyond reach became a man anyone could touch—but long after such a touch might have made a difference, when that touch was nothing but the expression of wishful thinking, a way of bringing a story to an end, of stepping out of a narrative so that someone else’s could begin.

Perhaps jealousy was what explained his last words to me: he was jealous of whatever was going to happen next. I would know, he wouldn’t, and he wanted to disrupt the pleasure of that privilege: lowering his newspaper, squinting outside through his huge eyeglasses, he reached for the glass of water by his bedside, and without turning around remarked, not incidentally, “I don’t know who you are.” Perhaps he didn’t really mean it. Or perhaps he did mean it, and felt his son looking for the answer to that question himself. Or perhaps he didn’t know who he was himself anymore, and the next assertion merely followed logically. So we too entered the German problem, father and son, absent to each other.

In the second story, “Romantic Landscape,” questions about my father’s painting took precedence over more personal concerns. The story related a visit I had made to my father late in his life. He was ill, sitting in a wheelchair on the veranda of a veterans’ hospital. He spoke little and remained noncommittal when asked about his work. Why had he stopped painting? What had happened to the youthful ardor, the sure hand, the powerful compositions?

There was no future to those questions, there was no future to this man. Viel Erfolg, “much success,” was all the old man said to me from his hospital bed, and I was left to make up the rest, to dream of a scene in which little children had gathered around Heinz Emil Salloch and watched him paint the bridge at Hohenfriedberg, as peasants in the field might have stopped their labors to watch van Gogh’s hands craft haystacks. Resigned fantasy rather than wishful thinking. Virginia, an old friend of mine, said: forget the stuff about reconciliation, about redemption. Forget about meaning washing up out of the twist in a bridge, out of charcoal lines that dissolve at the horizon like Heinz Emil Salloch must have watched his dreams dissolve even as he painted. How long was I going to go on romancing that particular ghost, Virginia wanted to know?

The night after I arrived in Berlin, I had too much to drink in the company of a German artist whom I shall call Graciella Y. We had met in Paris. We had agreed to see each other again in Berlin. We drank half a liter of white German Burgundy, then another. She talked about her tuberculosis as a child; I of my own good health. We laughed: the tuberculosis had been a better mother of invention than good health. Or in any case, good health had not been enough to vanquish the army of ghosts. Nor had a good education. Sometimes it came to me, I told Graciella Y. Imagine what a triumph it must have been for my parents, first-generation German immigrants, to have their son get into Harvard. Sometimes it also came to me how little difference it had made to me. Robert Oppenheimer had spent his undergraduate years milking Widener Library dry. It seemed to me I had spent those years just trying to find something I could hold onto, a woman, a meaning, a novel or two, a learned text. There was Thucydides, there was Peter Handke—anything that would prevent me from falling back into the whispers of the ghosts. Days, it was all right. What had I proved incapable of learning from my parents? They worked hard; they never watched television. They almost never spoke German.

♦

Said Graciella Y: “They didn’t have to speak German. They were in exile. Theirs was a universal tongue.”

Before 1933, after 1933. These are the divisions in Heinz Emil Salloch’s German work. Before 1933, landscapes dominate. They are filled with wind and breezes, zephyrs and the fluttering sounds of leaves in birch trees. Colors float across the paper, human figures wash laundry, walk side by side, a smile is never far, water floats up from canals, drifts lazily through the curves of rivers and laps at the bottom of the composition. After 1933we hear the wheels of purposeful activity on city streets, see the rush of smoke billowing out of chimneys, turn around at the rattle of trucks on steel bridges. The early landscapes are feminine, shapes are round; the stronger, darker urban works erect what Auden once called “the bare plan of a tree” in counterpoise to the naked purpose of a bridge. A time passes. Nature and mankind become one, a tangle of tortured ambition. In one painting, red flags whip across gray facades promising revolution while a sentimental creature in the foreground hunches in despair, waiting for the worst that he knows is still to come.

Before I brought the paintings back to Germany, I wrote a third story about my father, “The Shadowman and the Light.” It was less sentimental than the first two. It sought to explain what it had been like to be the child of people who lived their domestic lives in dark places, in pine-paneled living rooms, who drank dark rum, who played chess for hours without saying a word, who had dark secrets, who hardly ever spoke their own language.

It was not a story of laughter and forgetting, but only of forgetting. I fell asleep no longer remembering what I still thought I could discover. Had this solitary painter really dreamed of killing Hitler? Had Hitler been aggressed, Heinz Emil Salloch would have been dead fifteen minutes later. Why did he want to commit suicide? Why didn’t they talk German at home?

Through mutual friends, the German movie director Margarethe von Trotta heard about my story. She asked that I forward it to her. I discovered I was not the only one with the preoccupations I had considered strictly personal before then.

“Dear Roger,” von Trotta wrote, “I read your text or, as you say, your short story. Yes, it is a story, but I have the feeling it could go on and on, and that you have so many more things to describe about the darkness of your youth and your father’s silence and so many more to discover about yourself. Did you ask yourself why you are still today so linked to him? It seems to me that the reason can’t be only the exhibition of his paintings.

“As I told you my father was also a painter, he was well considered during the Nazi period and wasn’t forced to emigrate, but his paintings also became darker and darker at the end of his life. Did he finally understand that something went wrong in German history and in his own life? I never could ask him because he died when I was ten years old. I would have so many questions for him. So my darkness is a total one.”

♦

From Berlin I went to Halle to meet Bettina G., actually Frau Dr. Assistant Professor of Art History at the Halle School of Architecture and Design and an expert on Ludwig Kirchner. She had agreed to write a text for the catalogue and we finally got together at the Rotes Ross Hotel around nine in the evening.

“Shall we just ask for room service, have some wine? And a bite to eat?”

How long I sat in that hotel room while Bettina G. looked at the paintings, I don’t know. Time had stopped in Halle anyway. It was in the heartless heartland of the former East Germany, and the pedestrian walkways and new streetlamps didn’t do much to make the place feel any warmer than it had probably been in the last fifty years. I drank my wine. I was comfortable. I was in generous company—was it in her eyes as she looked at my father’s work, was it in her manner? I could feel Bettina’s thinking happening, could watch her ideas coalesce, and knew they would slowly fit and become an understanding.

I let my own thoughts wander. Rotes Rossmeans the red horse, and that led me to remember my great grandfather on my father’s side, an old Polish cavalry officer who, as legend had it, lost everything, home, holdings, title, and lands in one wild night of vodka and cards. He was last seen headed East, and never heard from again. There was a tendency to go missing in the family. On horseback, I always liked to think.

Finally Bettina G. glanced away from the gouache she had on her knees. “Look at this painting,” she said. “What do you see?” She waited patiently for my reply: I looked at the painting again. How well I knew the work. Of course what I saw was the bridge, the trees dissolving at the horizon, the rearranged walls of the barn, the solitude in the choices Heinz Emil Salloch had made of what he wanted to paint. I studied the composition again. Bettina’s question had focused my eye. Then I saw it distinctly. It was there in the lower left-hand corner of the piece. I pointed to it, the curious shorthand signature Heinz Emil Salloch had developed, a light assertion of his identity—as though in counterpoise to the swastika that must have been on everybody’s mind in those days, the prevailing iconographic symbol of its time, obliterating meaning with the same twisted anger with which it obliterated lives. His signature was firmly planted in the lower left-hand corner, and with it the almost shocking, irrevocable date—1933.

“Exactly,” said Bettina, her eyes half closed, as though time were laying fingertips on her eyelids, asking her to take a moment, to feel the weight of something that had no weight but that could nevertheless crush you with its mass. “Yes,” she went on, “1933. It’s a good painting but it is transcended by the power of the date Heinz Emil Salloch insisted on inscribing with such precision, like someone bearing witness, no? On the one hand, there is the year, time usurped by power, dictating its own truths. On the other, there is a watercolor. Not just art, but living history too. That is how we have to approach this exhibition. We need texts on the walls of the museum. We must help people put things in a context that makes it possible for them to see what Heinz Emil Salloch was going through. You know, if his later work resembles Kirchner’s mountain landscapes, it is not an accident. Kirchner went to Switzerland but went mad anyway. Perhaps it was good for Salloch that he went to the States.”

Room service knocked: they had brought us club sandwiches and a carafe of red wine. The carafe might have been modeled from the body of a swan, the neck was that long. “How elegant,” said Bettina G. The elegance was certainly incongruous, there in the middle of that dark night in that dark city. Outside, through the window, the walkway glistened. The ICE train would take me back to Berlin in the morning. I needed a good night’s sleep.

♦

#5 The path to the beach

I particularly like this painting—my father wrote to his mother, “Little Kate”—first because I painted it on your birthday and second because there it was that a young girl said something very nice and lovely to me, reminding me, for a year and a half now “without children,” how young people have always trusted me. The next Sunday, after the hurricane, there was nothing left, no fence, no telegraph pole, no path. Nothing but emptiness and the swamp. Nur noch Wüste und Sumpf.

The notebook was made of ten folded sheets of yellowed craft paper. The paintings and drawings all had separate numbers. Medium, date, place, and price. He wanted to know where he had been. He wanted to know what he had done. The meticulous way in which each entry was recorded had the aspect of ritual, gestures to ease the passage from Berlin to Lübeck, from Lübeck to the Westphalian plain. Or was it more than that: was he already fending off the doubts and fears, worried about the transition from being at home to becoming a homeless being, or from being a citizen to becoming an alien refugee, or from being at one with the light to going to another end of the prism where there was no telling how the shadows would fall?

On the outside cover of the notebook, a place and a street name were recorded: 67Argonnenweg, Adlershof. It took my friend Dorothee R., an information specialist, a day to discover that Argonnenweg had been renamed Steinmannstrasse by the East German municipality. The Argonne had been a major World War I battle, a principle German victory. Under Soviet tutelage, the East German regime had done its best to efface traces of anything that might lead the population back to a reverence for fallen heroes. It wasn’t just fathers who had disappeared. It was the idea of fathers.

We drove down along the Spree. On the far bank, old factories were being converted into elegant lofts. Along the river, commerce still plied its trade, barges and tugboats trundling up and down the quiet waters, though now sometimes forced to navigate between pieces of contemporary sculpture. Yet as we passed under the Jannowitzbrücke, 2005, Heinz Emil Salloch’s brush would hardly have had much touching up to do to bring “A 453, Jannowitzbrücke 1934, Medium, acquarelle, Datum 8/34, Preis, 12marks” up to date with the present landscape.

67Steinmannstrasse, Adlershof: the house was still there, a small corner building, on a street lined with trees. Two names on the doorbells, one German, one Vietnamese. Even had it proved possible, walking around in rooms where Heinz Emil Salloch had woken up, made coffee, sharpened pencils, looked out at the little garden, put a blanket over his shoulders, and sat down at a makeshift desk to do some more drawings, or to correct some papers turned in by his elementary school pupils—that would have been trespassing on something.

“Aren’t you touched?” Dorothee’s husband, Martin, asked me. I was silent. I just stared at the little house, stared at it unflinchingly, conjuring with spirits. Mysteries coursed through me but met a resilient pride: I wished there had been a second step, a studio with huge windows in Berlin. A studio with huge windows in New York would not have been bad either. I was a congeries of knots, some of which I knew were made of very German fibers. As we drove away, I said something to that effect: “Touched, I am not sure: But das hat sich gelohnt.” It was worth it. Martin remarked that since I had come to Berlin I had begun to lard my speech with German expressions. Were we watching a native son, being born? I considered all possibilities. It seemed unlikely, but what was likely, I could not explain any better.

We drove back to Berlin proper in silence. I believe I must have disappointed my hosts: they wanted exclamations of pleasure and pain. They wanted whole families to fall into place. But of course, they were German. Painfully they had pieced together the fragments of their own stories. My intimate little epic was child’s play compared to theirs. Yet I felt inadequate anyway, not even up to the closing rounds of this minor endeavor upon which I had embarked a few years back, felt out of sorts, felt perhaps the way Heinz Emil Salloch must have felt when he turned his back on Argonnenstrasse 67. However small and cold in the winter, and however small and very hot in the summer, the little house was nevertheless what he called home. I wondered what his suitcase was like when he left: a portfolio, a backpack? Did the painter he was even have a suitcase when he turned his back on his own country and began his trek into the annals of the missing?

I tried to take stock. I worked in Dorothee and Martin’s luminous apartment in Berlin. I began to sort through my feelings about this German enterprise. I began to be eager for it to be over, yet fretful too, about the reception I would get when I opened the suitcase in Eutin and watched Dr. Hahn react to the real thing, fold back the papers, examine the charcoal flourishes, the light passage of pastels over ink brushstrokes.

Did I think there was some way out of what Gerhard Richter evoked as the central German problem, the absent father, some way out of those obscurities? Or did I think there was a better way in?

Already it was Wednesday. I had an appointment in Eutin on Saturday at three in the afternoon. I would take a train from Berlin in the morning, get to Kiel on Friday night. On Saturday I would rent a car and drive the forty miles to the museum. Elegant and affable, Dr. Hahn would come down to the reception desk. And then . . .

I drank coffee in the morning and wine at night. I walked a great deal. I spent some time at a small coffee shop around the corner from where I was staying. One coffee shop right next door was run by an engaging Turkish couple but I preferred Yuki’s tearoom, which was down the road, closer to the river. The décor was minimalist, the homemade cakes were delicious and the coffee even better. Yuki stood behind her counter, behind her glasses, a slight woman with a volume of John Milton’s Paradise Loston the counter in front of her. Why was she reading that? Because she felt it gave one a way into the business of dealing with one’s own conception of God, and then too because in Milton’s text Adam and Eve were so human and, it seemed to her, might help one understand something about the nature of love.

That night I had drinks with Graciella Y. again. I mentioned Yuki to her. Graciella smiled knowingly. Her smile was like Yuki’s thoughtful expression when she mentioned the force of Milton’s text: it seemed to set consideration of God aside, we could get to Him later. God could wait. It was one of His qualities. Let us now praise famous men and women, said Graciella, consciously echoing Agee and Evans, praise the huddled, the terrified, the exiled, the lonely, the angry whose anger would go unrequited, or just the hopeful like Heinz Emil Salloch, one emigrant among so many, fleeing across the sea and into the arms of the unknown.

♦

#3 Evening on the sound

Once I stayed very late and alone on the beach, just went on walking until I got to this small inlet. My painting finished, with a harmonica and just the stars to guide me, I returned home. It was already night and I was very hungry. Love, your son.

Heinz Emil Salloch lived in Kiel from 1927 to 1930 and moved three times. Adolfstrasse, Richtmanstrasse, and some other place that I could have found out about, noted its name in my journal—but didn’t. I hadn’t even gone to 24 Adolfstrasse to try to imagine what it had been like for him to walk up what I was sure was a cold-water garret with a toilet down the hall, if that. This had never been conceived as a trip of fealty, the accomplishment of some duty, a noble but sentimental completion of one of life’s obligatory stages. I distinctly remember opening the suitcase in my friends’ living room, opening it again to make my point, and with theatrical emphasis telling them, “This, and these, these pieces of painted paper, that is all this whole expedition is about.” And I distinctly remember Martin, saying, “Well, we will see about that.”

I went on seeing about it. I slept well in the hotel by the sea, and went for a long walk in the morning. This was not Hamburg, nor was it Lübeck, on the other side of Germany’s access to the Baltic: there was nothing picturesque about Kiel. The eighteenth century, the nineteenth century were almost entirely gone, destroyed by the war. Buildings were either makeshift or they were permanent glass towers of twentieth-century enterprise, of German efficiency and drive. The port was in full swing. Travelers to Scandinavia waited patiently in line to get their automobiles onto the huge ferries. Glass office buildings vibrated with orders from all over the globe. And just below them, dives and cafés put out a purple neon welcome to sailors and any other parties who might be interested in drink and smoke and coarse jokes and female company. Cardamom and smoked fish and ground ginger and engine oil and the intrigues of all the adventure novels I devoured when young hung in the air. Emphatically this was a port. I turned back to the hotel. I wasn’t leaving. I was arriving. I had a good lunch.

Only a big Mercedes was available for rent at Avis. It was dark blue except for the thick leather of its seats, which was nearly black. The mammoth suitcase fit into the trunk with room for the luggage of several fellow travelers. But there were none. No friendly hand would lean across the front seat and open the door for me from the inside. Perhaps no one else would have wanted to be around. Destiny was a big word: it could make even close friends uncomfortable. They had learned to stay away from it. They wanted its fruits, not its growing pains, hoped I would figure it out on my own. Destiny was for the screen, or eulogies, or unspoken regrets. Destiny was someone else’s problem, someone else’s solution, preferably clearly legible, and in Technicolor, darkly etched against a glowing sky. Driving through northern Schleswig-Holstein that early afternoon, it felt appropriate to be alone.

Fields beckoned, the hills were gentle. Other drivers were careful. No one was in a rush. Midday was luminous. Sunlight streamed through clouds to play havoc with my awareness: when finally I concentrated again, something my wife once said came back to me with insistence—we should always try to tell the truth “anyway.” Why? Because the truth is always so much more interesting.

The only painting I have not brought with me to Eutin is a study of a nude woman, dated 1933. It hangs in my living room. It is large, and the woman is seated with her face turned away from the viewer. At the same time, she is exposed: her breasts are small, her thighs ample, her feet only partly finished, her hand rests lightly on the bench that supports her hips. The pose must have been easy to hold: she might have been there for hours, yet the drawing suggests a tension: Is it in her hand that holds her body away from the painter? Is it in the weight of a head that is almost out of proportion with the rest of the study? After Kiel, Heinz Emil Salloch must have taken a few classes in life drawing. Did he know this woman? Did he pay her to pose? Before the exhibition opens, I know I will add this drawing to the collection. Its place is in Eutin.

♦

Eutin, three o’clock that afternoon. The village was quiet. Behind the brick walls that lined the quaint streets the tips of garden trees shot toward the gray sky and seemed to loft a canopy of prosperity over the surroundings. I had parked close to the castle that shelters the Ostholstein-Museum but I was five minutes early. I wandered among the shops. After the butcher shop with its huge choice of sausages, there was a lingerie shop, without many choices at all. On a street corner, four men argued the virtues of the new Chancellor. That she was a woman didn’t matter; that she was selling out to the Americans did. I stopped wandering and walked toward the museum, my suitcase clattering behind me.

Dr. Hahn was expecting me and moments later we were upstairs in his office. Coffee cups, paper cutters, posters for the next exhibition. He cleared the desk.

For the last time I hoisted the suitcase. I set it on a sturdy cabinet. I opened the seals on my beast.

Outwardly I was calm. Inwardly my demeanor was otherwise. Three years ago my heart had soared when I was told it would be possible to do an exhibition. Out of the darkness into the light, out of the shadows into the bright attention of people who would look at the work and see some of their own history. But what would Dr. Hahn say? Would he be disappointed? Would he finger the paper speculatively, grimace a little, smile, shake my hand, and say he looked forward to seeing me again, in September when the show would open, wondering how he was going to squeeze this work in between his other ongoing concerns?

But Dr. Hahn was thrilled. He made gruff sounds and squinted with pleasure. “Yes, yes,” he said and repeated. He went back to the work. I had more coffee. At last he was finished. He nodded and smiled. In the fifty pieces I had had photographed for eventual use in a catalogue, he said he had more than enough for a good show. But he wanted to keep everything, examine it closely. He was fascinated by Heinz Emil Salloch’s repertoire, saw that each item could be located in the logbook—and like the very good museum director I knew him to be, began to compare, trying to locate the pieces that could be traced back to Lubeck. There was a foundation in Lubeck that supported arts relating to that city. Perhaps we could get some help.

It was not yet dark as I drove back toward Kiel. The road floated ahead of me. The horizon seemed to want to lift the road higher, up toward that light. I knew there was a phrase in German to describe this late afternoon phenomenon: Es wurde breiter, it became wider. I pulled off to the side of the road. I took some photographs of the fields around me, black and white. I tried to imagine that the images would speak to my father, tell him that es wurde breiter. In the optimism of that moment, I could see him nod.

During my travels, in my several hotel rooms, at night before I fell asleep, I would read passages from a book I had brought with me: Robert Musil’s diaries, 1899–1942. I had read his novel The Man Without Qualities when I was in college, and I was feeling a bit like his hero when I left New York with my Samsonite, not sure of any of my qualities except determination.

Musil’s thinking was vast, his notations warm. He was full of curiosity for other people’s curiosities and intrigues. “Work in progress” meant nothing to Musil. Everything was work in progress.

“In truth one does not function in this mode or that; the way things actually happen is that, when one comes into contact with other people, they strike within one a quite specific (or quite unspecific) note—and this then is the mode in which one functions.”

And:

“Intellectual progress has always simply consisted in correcting, at every stage, the errors that one produced at the previous stage.”

And what about emotional progress?, I wondered, sitting in a restaurant in Kiel. I was alone. I had my Musil, I had had my meeting with Dr. Hahn, which wasn’t even a memory yet. I didn’t need anything else. I liked the restaurant: the food was good, the lighting was soft, the building was one of the few in Kiel that had not been destroyed during the war.

I paged through the volume, and watched as a strikingly glamorous woman came in and sat to my left. Her skin looked as golden and as velvety as the white Burgundy I was drinking. When her friends came in and she departed for a large table on the other side of the restaurant, I went back to reading, and saw that Musil had been watching me the whole time.

“[W]hen one comes from a garden where the sun shines warmly one is assailed by the fragrance of the strongest flowers. And women are a perfume that nests securely in our nerves.”

Perhaps I looked up at the ceiling, just then, wondering about angels, longing for a fresco. Maybe I was possessed by a new sense of purpose, or maybe I just ordered another glass of white Burgundy. I do know that I did suddenly glance under the table, because I had spent the past two weeks always looking back over my shoulder, checking to make sure my suitcase was still safely in place, at my feet—my burden, my accomplishment, my friend, my sea trunk.

But of course, it wasn’t.

There is a word to describe exactly what happened at that instant: Epiphany. It means a moment of great and sudden revelation. Usually it has a religious connotation. If I looked further in Musil, would I come across an accounting of how such an event would be possible in secular terms? Or did I have to retreat to Proust, or to Wordsworth and Keats? Perhaps an epiphany was exactly what had no explanation. It does not come with the rush of memory, or show up on a video tape: it grows from buried longings, or from a stalk where buds appear only to the eye that didn’t know it was paying attention. How grateful I was suddenly to Dr. Hahn for having taken the whole suitcase unquestioningly. How grateful I was to . . .

My finger was on a line in Musil when I froze at my table, or rather when some force immobilized me there, as if in anticipation of a gift I could not believe I was about to receive. You know where I was: Kiel. You know what I was doing: drinking. You know that I was thinking whatever came to mind, whatever Musil thought might intrigue me, these thoughts keeping me company as friends, keeping myself company, until suddenly the thoughts themselves vanished and in their place was Heinz Emil Salloch in his chair. In his rocking chair, in his wooden chair at the head of the table as I was growing up, in the chair where he played his lute, in that last wheelchair, his back to me, his voice coming at me like an echo: “I do not know who you are.” Only now he had turned around and he was looking at me. There was so much more going on in that face than I knew I would ever understand. He shrugged. Why bother trying? He was right. It was my turn to speak.

“Well,” I told him, as though time had suddenly been suspended and everything was again happening all at once, but this time for all the right reasons, as though with me pulling, and he guiding, we had crossed the chipped and tarnished lacquer of the years together, gotten the cart to the temple, and were standing there side by side, me, exhausted, and he, never to be tired again, for after all, he was dead.

“Well, old man,” I said, “Now you certainly do know who I am. I am your son.”

A gallery of Heinz Emil Salloch’s work can be viewed online.