from NER 38.1 (2017)

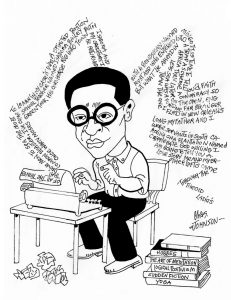

NOTE: Charles Johnson has shown exceptional talent in a wide variety of artistic endeavors: cartoonist, novelist, short story writer, essayist, screenwriter, and educator. Johnson, who established an early reputation as a cartoonist, received his undergraduate degree in journalism from Southern Illinois University while working with and under the guidance of novelist John Gardner. He earned a master’s degree in philosophy and a PhD in philosophy and aesthetics from State University of New York–Stony Brook. Johnson joined the faculty at the University of Washington in 1976. In the spring of 2009, Johnson, who had held the S. Wilson and Grace M. Pollock Professorship for Excellence in English and was the former Director of Creative Writing, retired from teaching.

NOTE: Charles Johnson has shown exceptional talent in a wide variety of artistic endeavors: cartoonist, novelist, short story writer, essayist, screenwriter, and educator. Johnson, who established an early reputation as a cartoonist, received his undergraduate degree in journalism from Southern Illinois University while working with and under the guidance of novelist John Gardner. He earned a master’s degree in philosophy and a PhD in philosophy and aesthetics from State University of New York–Stony Brook. Johnson joined the faculty at the University of Washington in 1976. In the spring of 2009, Johnson, who had held the S. Wilson and Grace M. Pollock Professorship for Excellence in English and was the former Director of Creative Writing, retired from teaching.

Among his many and varied accomplishments are four novels, Faith and the Good Thing (1974), Oxherding Tale (1982), Middle Passage (1990), and Dreamer (1998); three collections of stories, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1986), Soulcatcher and Other Stories (2001), and Dr. King’s Refrigerator and Other Bedtime Stories (2007); and works of philosophy and criticism such as Being and Race: Black Writing Since 1970 (1988), Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing (2003), and Taming the Ox: Buddhist Stories and Reflections on Politics, Race, Culture, and Spiritual Practice (2014). In addition, as a cartoonist and journalist in the early 1970s, Johnson published more than a thousand drawings in major publications. He has received an international Prix Jeunesse Award and a Writers Guild Award for his PBS drama Booker (Wonderworks, 1985), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1986), two Washington State Governor’s Awards for Literature, the 1990 National Book Award in fiction for Middle Passage, a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellowship (1998), and the Academy Award for Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (2002), as well as numerous other awards and several honorary doctorates. His books have been translated into many languages. A public intellectual for several decades, he is a well-respected artist and author whose work integrates literature, spirituality, race, and philosophy. It would be an understatement to say the interview was engaging; Johnson was thoughtful, energized, animated, and bubbling with spontaneity even after three hours of questions. Our conversation took place at the University of Washington on Thursday, May 5, 2016. —NGN

♦

NGN: Let’s start at the beginning. Could you tell us a little bit about growing up in Evanston, Illinois?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I was born in Evanston on April 23, 1948. April 23, they say, is Shakespeare’s birthday. It was a very interesting time to be growing up in Evanston, which was for many people a model community—a very progressive community. I grew up in the shadow of Northwestern University. I went to a high school that had been integrated since at least the 1930s when my mother went there. It wasn’t a paradise, but people used to call Evanston “heavenston.” It was an easy place to grow up for a kid. In elementary school I got praised and patted on the head most in my art classes. I was always just dying to get to art class because those were the classes where I came alive.

NGN: Where did that love of drawing come from?

CHARLES JOHNSON: It’s just a talent I had. One is born with it; it just needs to be developed by a good teacher, although many artists and cartoonists are self-taught. I remember I had a blackboard that my parents gave me for Christmas—a three-legged blackboard. This was before we moved into our first house. We had an apartment, and I would sit in the kitchen with the blackboard and draw. I would get lost in it. By the time I was finished my knees and the floor would be covered with chalk. There would be this little sliver in my hand because I would draw and then erase—draw and then erase, draw and then erase. I would see things in my mind—in my imagination—and projecting them out there on the page or on the blackboard was like a relief. Nobody could see these images in my head, but once the image is on the canvas, there it is for the entire world to see. I remember I would be playing with my friends and all of a sudden an image would come into my mind. I would stop cold. It would be so powerful. I could see it in front of me. Another kid would say, “What’s the matter with Chuck?” And my best friend Kent would say, “Oh, he’s just thinking.” That probably was the beginning for me—a strong visual imagination as a kid.

NGN: You attended Evanston Township High School, which was one of the best high schools in the United States in the 1960s. Did you have any sense of its importance at the time when you attended?

CHARLES JOHNSON: We knew. We were told we were number one or we were number two. We would switch off with New Trier, which was another local high school. We knew it was a special place in the ’60s. My graduating class was almost a thousand people, and the school was like a small college. What made all this possible were wealthy white Evanstonians who paid for that education for their kids; and the black kids—we made up 11 percent of the student population—benefitted from that. So I took art classes, photography classes, literature classes, and worked on the student newspaper: drawing panel cartoons, comic scripts, and short stories. In 1966 I received two second-place awards for a sports panel and a comic strip called “Wonder Wildkit,” which I collaborated on with a friend named Tom Reitz, who started as a sophomore at Harvard after we graduated—he placed out of his entire freshman year. That’s how good academics were at ETHS.

NGN: You published cartoons in your high school newspaper and at the same time you were being paid to draw illustrations for various companies. Then when you entered Southern Illinois University in 1966, you continued to draw cartoons and to do comic strips for the student newspapers, while simultaneously producing political cartoons for the local town newspaper, the Southern Illinoisan. Can you give a sense of what it was like to be a professional cartoonist at eighteen?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I went off to college as a professional artist because I made my first sale when I was seventeen years old, my junior year of high school. The first thing I did when I hit campus was to go over to the college newspaper, which actually was part of the journalism school, and show them my published material. I got my first assignment, which was drawing something about the college president, and from that point on I just drew for four years: illustrations, editorial cartoons, comic strips. And they paid. It was a good journalism school, actually, started by Howard Long, who was an old newsman. He liked my work; I remember that. When he gave me something called the Delta Award in 1977 for “significant contribution to intellectual commerce in our time,” he said, “I’ve only known two geniuses in my life, and both of them were cartoonists.” Those years were a lot of fun for me. Actually, I had planned on going to art school—all through high school I dreamed of that, of doing art every day. I was accepted at an art school in Illinois, and then, at the last minute during my senior year, I bailed out—partly because my art teacher one afternoon droned on and on about how artists starve and have such a hard life. I was pretty sure he was talking about his own fate as an artist, but I nevertheless went to my adviser and told her what my art teacher had said—that I’d be better off going to a four-year college and not an art school. This was in May 1966. I told her everyone had their school acceptances already, including me. Who was still accepting students? She looked at this big book of hers and said Southern Illinois University. You worked on the high school newspaper, she said, so you can draw as well as write if you major in journalism. I said, okay, that’s what I will do then. When I got to campus, my whole intention was to draw. I was different from the other students I knew in that sense.

NGN: You stated early in your career that an artist “has a very special sense of the world.” Do you still subscribe to that premise?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Artists are different from most people in that they are very sensitive. Things that maybe don’t hit other people quite as hard, in either a good or bad way, hit an artistic person very hard. One of the things you are going to have to do if you are an artist in America is to get over some of that sensitivity and have a thick skin to deal with rejections and being misunderstood. An artist will stop and look at something that other people will ignore and just ponder it and be fascinated by it. For me, as an artist, I never want to lose the sense of mystery and wonder about the world in which I live. A sense of mystery and wonder inhabits everything about the human experience.

NGN: One of your cartoons that I continue to see online is the one with Richard Nixon and his long nose. This was before Watergate. This cartoon tells so much about Nixon and also his downfall.

CHARLES JOHNSON: I do remember doing a couple of Nixon cartoons. I drew Nixon with a vulture on his shoulder as he says to an aide, “When is Henry (Kissinger) going to send us some doves?” Actually, that was drawn damn well!

NGN: Back in the early 1970s, you began your career with Black Humor (1970) and Half-Past Nation-Time (1972), two books of political cartoons. What was it about this aspect of your career that encouraged your transition to writing?

CHARLES JOHNSON: In that seven-year period, from 1965 to 1972, I worked so intensely at drawing, two books as you said, hundreds—thousands, probably—of individual panel cartoons and illustrations. I also did a TV program where I taught people how to draw, one of the early PBS shows, Charlie’s Pad. That show was on the air on PBS stations nationally in 1970, the same year that Black Humor was published by Johnson publications in Chicago. I think that was the culmination. There was a piece in the school newspaper about the book and TV program, and the first sentence was “It is not often that you talk to another student and ask how are your TV show and your book doing?” I remember that interview because she asked me, “What do you want to do next?” and I said, “I am interested in writing novels.” I was transitioning to novels then because there was a novel I had to write, a story that wouldn’t leave me alone. If you look in the bound manuscript I gave you (The Way of the Writer: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Storytelling, Simon & Schuster, 2016), there is a chapter called “The Apprentice Novels.” It talks about the six books I did before Faith and the Good Thing.

NGN: Before we come back to politics and writing, could you tell us a little more about the TV series you mentioned?

CHARLES JOHNSON: The year before we started shooting, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting had been founded by Congress, and that meant that local stations all around America had a chance to apply for money to do shows. But they needed content. All WSIU-TV needed to have for the show Charlie’s Pad was me and a drawing table and two cameras. It was extremely cheap to do. And so we knocked out fifty-two of those shows in less than a year. It was on the air in the spring of 1970. I get letters from people, to this day, who say that they saw the show when they were kids and learned how to draw, and now they draw for their children. I have a box of letters like that. And when I was done with this series, when I was twenty-two years old, I realized something about myself. That was the fact that it was no thrill for me to be in front of a camera. I was more interested in being behind the camera writing scripts.

NGN: Black cultural nationalism was robust in the 1960s. You received a lungful of tear gas thrown by the Carbondale police at students. Were you involved in the racial politics of the 1960s?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Well, I wouldn’t call myself an activist, but my work got so radical towards the end that the white editor, the faculty supervisor for the Daily Egyptian, the student newspaper, called me in and wanted me to stop. My editorial drawings were calling for a revolution—calling basically for a Marxist revolution. He wanted me to go back to gentler subjects.

NGN: During the era of black radical politics in the 1960s, your cartoons exposed sexism and how women were treated by leaders of the Black Power Movement, which in some sense undermined the political sincerity of black radical leaders. Did you get any pushback because of those cartoons at the time?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Well, there were guys who were talking black separatism but dating whites. That was happening, and everybody knew it. I wasn’t saying anything people didn’t know. As a cartoonist and as a journalist, I felt free to go anywhere that my imagination took me. Sometimes in the student paper, there would be a letter or two objecting to a cartoon I did, but that is just part of the territory. If you are a journalist exercising your First Amendment rights, you are going to make somebody mad. That’s okay. That’s what cartoonists do.

NGN: I know that your politics were very different from Amiri Baraka’s politics, but you have acknowledged that when he gave a reading on the campus at Southern Illinois University, he impacted your life greatly. How did he energize you?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I think it was in January 1969. The black graduate students made a big effort to bring him to campus. He did a reading and a Q&A where he only answered questions from black students. He said no questions from white students. And one thing he said that stuck with me more than anything else was what he told the black students present, “Take your talent back to the black community.” I thought he was talking to me, because up until that time, I had been working as a cartoonist intensely but not with black material in terms of culture, history, and all of that. So I went to my dorm and spent the next week intensely drawing black humor. The book was done in a week. Some of the drawings were done so fast I felt like I needed to redraw them before the book came out. I would still redraw some of them today if I had the chance. I did several manuscripts like that. I did one on slavery, but the publisher, Aware Press in California, ran off with it and never published it. But they did publish Half-Past Nation-Time. I did several cartoon manuscripts, about a hundred-something pages for each. One was on Buddhism, and some of those are in a lovely little book titled Buddha Laughing, published by Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, for which I serve these days as a contributing editor.

NGN: Your cartoons were multilayered, multiplotted, and visually engaging. You were not afraid to be biting and satirical, and you were not afraid to challenge and find humor in various complex situations. But you also made the attempt to be neutral and not just radical.

CHARLES JOHNSON: As I said, there were some that were so radical I was surprised the faculty advisers for the newspaper let me publish them. But I was young then, in my late teens and early twenties. At that age, I was all about testing boundaries and limits, especially my own limits. As I started graduate school, though, the subject I really cared about was philosophy. When I did my master’s degree, I was still very radical. My master’s thesis was on Marx, Freud, and Wilhelm Reich. And then I went to Stony Brook and first taught as a TA a course called “Radical Thought”—because of my master’s thesis. I taught everything from Marx’s “1844 Manuscript” down to Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book.” I think that was 1974–75. But Marx will lead you to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind, and Hegel to Kant, then Kant will take you to Hume, and he will take you to Locke, who in turn will lead you back to Descartes. As I began to immerse myself in the theory and method of phenomenology, I was also moving towards Eastern philosophy, Buddhism, for example, because it had been a personal passion of mine since the day I first practiced meditation as a teenager.

NGN: After leaving cartooning behind for twenty years, you returned to cartooning, particularly for Quarterly Black Review, where you used your cartoons to comment on racial politics. Why was that important for you?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Well, the thing is, as a professor of English here at the University of Washington, I had to concentrate on literature. I had to reinvent myself. I’ve done that three times in my life. The first time was as a cartoonist and illustrator in my teens and as a young person. Then I had to reinvent myself as a philosopher in order to earn my PhD (and also because philosophy is as much a passion for me as art is). Then I had to reinvent myself as a literary person—as a teacher of creative writing, as a literary scholar. All of those areas cross-fertilized each other.

NGN: Where did philosophy come into play for you as a writer?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Journalism majors in 1966 at my school had to take two philosophy courses. One was required and the other was an elective. The required course was logic, because the faculty in journalism wisely understood that a class in logic would be a good thing for journalists or reporters to have. Then the elective I took was on the pre-Socratics. A professor who was new to campus, John Howie, taught that lecture course. Just hearing him talk about the pre-Socratics made me understand that their questions were my questions. The questions of the good, the true, and the beautiful—those were my questions. I realized I had to do philosophy for the rest of my life. That was the beginning of my passion. Philosophy to me is simply the love of wisdom. Literally, that’s what philosophy means. I dreamed of a PhD in philosophy from the time I was eighteen years old. And not just Western philosophy, but Eastern philosophy was enormously important to me. I first meditated when I was fourteen on my own, and then I studied Eastern philosophy as a passion, as a secret passion, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism—all through the 1960s and early 1970s. I talked about that in my book Taming the Ox.

NGN: What do you think students are now missing by not studying philosophy?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Something like 70 or 80 percent of schools had philosophy as a requirement in the early twentieth century. I have seen figures in the past twenty years or so that place a course in philosophy as a requirement in only about 17 percent of the schools now. I think that is an enormous loss because we are talking about the humanities here—the liberal arts. Philosophy was always central to that. Everything used to be a part of philosophy. Physics broke away in the seventeenth century. Chemistry in the eighteenth; biology in the nineteenth century; psychology broke away and became a separate discipline in the twentieth century; but they were all part of philosophy for two thousand years. And so to understand the liberal humanist vision—to understand the liberal arts and humanities—you have to have an appreciation for philosophy. But no, we don’t have that now as widely as we once did. And we have also gotten rid of, to my shock, foreign language study in a lot of places. In the creative writing program here we used to have a language requirement; we don’t have it anymore.

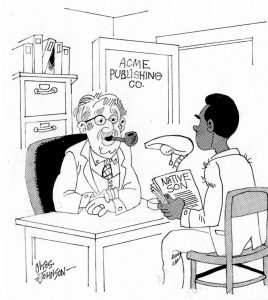

NGN: Since we are talking about philosophy, black philosophical fiction is also something that is important to you. Why was it so important to you?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Because philosophy is so important I have a natural enthusiasm for philosophical fiction. We don’t have much of it in America, unfortunately, and there are reasons for that. We don’t have many philosophical writers. Among black philosophical writers, there are only three that I typically identify with, and they are Jean Toomer, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright. You see the philosophy in their works. With Wright you see his emergence first in Marxism, then when he goes to Paris he studies Husserl’s phenomenology with Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre. They both tutored him on phenomenology, and he gets the flavor of existentialism in his story “The Man Who Lived Underground.” Ellison, of course, has a very Freudian kind of surrealistic and comic exuberance in his novel Invisible Man. And then Toomer was oriented toward the East—his exposure to Gurdjieff, who was influenced by Eastern thought.

NGN: You stated that Martin Luther King Jr. is a philosopher and we should talk about him in those terms and not just as a civil rights leader. Would you expand on that notion?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Yes, he is a trained theologian. And so in my novel Dreamer part of my effort was to give that sense of philosophical and theological fullness of King. He is not just talking about integrating lunch counters and buses. There is a larger vision that he has of which that is part. That vision involves the beloved community, as he called it. He urged the Freedom Riders to remember that their ultimate goal was the beloved community. You don’t see people use that phrase very often now. King gets one-dimensionalized sometimes as a civil rights leader and a spokesman for black people; but he is much broader, and you see that in his favorite sermon, The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life. That was the sermon he gave to get the job in Montgomery. That was the sermon he gave when he went off to Europe to get his Nobel Peace Prize. That was his favorite sermon.

NGN: In Dr. King’s Refrigerator and Other Bedtime Stories you explore King’s appetite for food and how that led him to the truth of interdependence. Could you expand on this?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I started a reading series in Seattle in 1998 called Bedtime Stories for Humanities Washington. The beauty of the series is that every year I get a new story out of it. I have now written eighteen. The board at Humanities Washington gives three or four writers a theme—for this coming fall, the theme is going to be “In Your Wildest Dreams,” and we have to figure out over the summer a story that touches on that theme. During the year I wrote Dr. King’s Refrigerator, the theme was a midnight snack, and so I began thinking, okay, I’m going to have a character who gets hungry in the middle of the night and wants a midnight snack. I tried to write the story but I couldn’t, because I didn’t know who he was—the character. So, I said, let me go to bed and I will try to figure something out tomorrow. I have a set of the World Book Encyclopedias from 1954 my parents gave me when I was six years old. I keep it because I grew up with it and I love those old entries. I got up the next day and pulled down the F book from the set and looked up food. I said to myself, let’s just forget everything I think I know about food. Let’s do the phenomenological epoché on the phenomenon of food. And as I looked over the World Book material, I realized the production of food involves what Buddhists call pratityasamutpada, or interconnectedness. It’s what Thich Nhat Hanh calls “interbeing.” The next question I had to ask myself was, who is going to discover that? Immediately, I thought of Dr. Martin Luther King because he talks about the network of mutuality that characterizes all of our lives. But I wanted a King before he becomes “King”—a year before the Montgomery boycott, when he is just a graduate student trying to finish his dissertation and is newly married. It is just one night we see in this story, and the story has a very simple action—a psychological change for the protagonist King. That is one of my most anthologized stories because, I think, it has a spiritual message, and it is about a young King. I did seven years of research on King for Dreamer.

NGN: In 1974, your novel Faith and the Good Thing was published. But before that, you had written six unpublished novels, what you call your “apprentice novels.” You were twenty-six. Did anyone tell you to slow down?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Well, I love to create and there have been people throughout my life, yes, who would tell me to slow down, who didn’t understand why I was doing a particular thing. I didn’t listen to them. I never listen to negativity. As a black artist in white America, I’ve had to not listen to all sorts of people—whites and blacks—who tried to discourage me or couldn’t understand what I was doing and why. But I’ve always believed in myself and trusted my God-given talents. I believe James Baldwin addressed all these matters well in his essay “The New Lost Generation,” published in the July 1961 issue of Esquire. There, Baldwin said, “A man is not a man until he’s able and willing to accept his own vision of the world, no matter how radically this vision departs from that of others.” To me, art is life, creating is life. You are right; I did a lot of work. As I said, I have reinvented myself three times in the course of sixty-eight years.

NGN: Back in 1978, you advocated, and this is a quote, that “Writers should be able to write everything, anything. You should be able to write novels, radio plays, operas, short fiction, gags, manifestos; you should be able to write philosophy, epic poems, screenplays, and charms to raise the dead, blight your enemies, and kill rats, everything.” Now, since you have traveled the journey as a writer, do you still subscribe to the premise that a writer should be able to write everything?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Yes, I do. One of the things I’ve enjoyed since I retired from teaching is that I have worked on lots of different things just for the sake of curiosity. I have done a lot of work in the last six years—even since retirement—and it is because I enjoy it. Here it is: art, the creative process, consists of at least two things. One is you have the process of discovery—this is why you get up every day and do art, because you discover something new that you would not have dreamed of before; second, the creative process is about problem solving. And the more you do and the older you get, the more ways you know how to solve a problem. I can work faster now than when I was in my twenties and thirties. I can whip out a document in a day or two usually. Again, you don’t make the mistakes that you made as a younger writer. You don’t have to learn those things. They are right there at your fingertips. When you get to be in your sixties, and presumably in your seventies, those should be the richest, most fertile and productive times in your life, because now you can draw upon all that knowledge and experience.

NGN: When I think of just how prolific you have been, there is only one other person that readily comes to mind, and that is W. E. B. Du Bois.

CHARLES JOHNSON: Du Bois? Well, I’ll have to think about that because Du Bois is one of my heroes. My heroes have always been prolific artists—fine artists, even pulp, pop artists. My teacher Lawrence Lariar published over one hundred books; some are junk books, murder mysteries that he wrote under a pseudonym, but he was prolific. John Gardner was prolific; he published about thirty books in many genres. And, believe it or not, I have a great admiration for those pulp writers of the 1930s and 1940s, who were turning out work for less than a penny a word. They had no idea that their works one day would become part of the culture, pop culture. They were just doing the job. And they didn’t look back. Those were professionals, and they were journeymen, and that is what I admire.

NGN: In Being and Race (1988), you were critical of limitations placed on creative freedom, particularly the premises that come with Black Nationalism, or a black aesthetic framework. Have you changed your position?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I haven’t changed my position for this reason: If you are going to be a prolific artist, you need to expose yourself to as much art as possible from every historical period, from every country, from every culture—everybody regardless of their race, class, gender, cultural, or religious orientation. Doing so increases your toolbox of techne or technique, your artistic strategies, and that enables you to be a prolific artist—if you limit what you look at, you limit the tools and strategies that you deploy. That’s always been my problem with the Black Arts Movement, which was the literary or artistic wing of the Black Power Movement—it was separatist. It was self-limiting, and I don’t like limitations. So from a very practical standpoint, I still stand by the position I took in Being and Race.

NGN: You clearly opposed the notion of a white aesthetic or a black aesthetic. How would the politics of Black Lives Matter play into that discourse? You wrote about your view of the Trayvon Martin incident. What is your position on Black Lives Matter—any comment?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I don’t really have a comment. But I don’t think there is such a thing as a “white aesthetic.” I think you have lots of white people with different aesthetic positions. And there is no such thing as a single “black aesthetic,” because the spirit and vision out of which one black artist works is not necessarily the spirit and vision out of which another black artist works. There is no white or black aesthetic. That was really a bad idea back in the 1960s, in my opinion.

NGN: You stated that you have always been an integrationist. Does that mean you have been against the political position of Malcolm X and such?

CHARLES JOHNSON: We always position Malcolm X against King because of his criticism of integration, but Malcolm X said something in the 1960s that has stuck with me until this very day. He said this to the integrationists: “Why do you want to be integrated into a burning building?” That is a hell of a quote. That is one I have thought about my entire life. What does it mean to participate in American society? Are you going to participate in those things in American society that are dysteleological, that are questionable morally? No, I don’t think so. I don’t think we should do that as black people. My position towards Malcolm X and Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam is not against the black self-reliance dimension they promote. I love that. But I am not a racial separatist. Here at the University of Washington, just as at Middlebury and just like Columbia, two schools you know, I taught students from every kind of background: whites, blacks, Africans, males, females, Asian students. I couldn’t afford to be separatist if I wanted to be a good teacher capable of serving all my students.

NGN: I came across an interview in which you stated you’d thrown away about three thousand pages from the writing of Dreamer. A streak of pain hit my stomach, and the pain worsened when I continued to read only to discover that you also had thrown away about three thousand pages from Middle Passage. Don’t you think about leaving that material for scholars?

CHARLES JOHNSON: No. As an artist, I want to give you my best, my best feeling, my best technique. That’s what it means to be a professional. If I have done scenes or pages that are not my absolute best, then I don’t think anyone needs to see them.

NGN: You have stated that your kids had an impact on the way you thought about and looked at the world, suggesting that they also influenced your writing.

CHARLES JOHNSON: When I write a novel—or any book—I write it as if it is the last thing I am ever going to say in this world. That’s why it is worthwhile putting five years, six years, or even seven years into it and throwing out three thousand pages. This could be my last will and testament in language, because I could put this manuscript in the mail at the post office and walk back to the parking lot and be hit by a car and killed. In which case, these words, this manuscript is the last thing my kids (or anyone) will be able to look at and say this is what Dad really thought up to the time of his death, this is what Dad believed. This is his literary and intellectual last will and testament.

NGN: Do you still keep a journal?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I used to keep one regularly earlier in my life. I was thinking about things last week and I pulled out my journal, and I realized that I had not written in it in a year. The last dated entry was a year ago. I don’t have the need to do it that I used to have when I was young because so much of my thoughts and feelings are already in print in my stories, novels, and essays. I have filing cabinets full of those journals. But I told my family to do what former Pope Ratzinger said he is going to do with a diary he kept during his time at the Vatican: “You’ll have to burn my dairies and journals if I go before you.” Back in the 1970s, the diaries and journals were a place for me to express myself, and think on the page about literature, black literature, and American culture. Now I’ll just write and publish an essay about what I think or feel.

NGN: You have often talked about the excitement and interest John Gardner brought to American literature. How did Mr. Gardner aid your career as a writer?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I have written a lot about John. I wrote the introduction for his book On Writers and Writing. I have a piece on Gardner’s mentoring in The Way of the Writer, and I wrote the introduction for his first best-selling book in 1972, The Sunlight Dialogues. John brought an excitement to literature that was based upon invention and imagination, and he was also very critical of bad writing. He brought an excitement to literature that we have not seen in a very long time. Also, he had a position that he took called moral fiction. For ten years, he was very prominent as a writer and critic, from 1972 to 1982—like a comet blazing over the literary landscape until his untimely death in a motorcycle accident.

NGN: Slave narrative is now something that is being studied, but I’ve heard you refer to “metaphysical slave narrative.” What do you mean by that?

CHARLES JOHNSON: When I started Oxherding Tale, my intention was to write a philosophical slave narrative for the late-twentieth-century reader. In other words, it uses the essential form or structure of the slave narrative, and I play around with the conventions of that confessional genre, especially in two chapters that talk about the slave narrative form and the philosophical implications of first-person narrative. When I say metaphysical slave narrative, what I mean is that this is a slave narrative that is not exploring just physical bondage of chattel slavery. It is exploring other forms of slavery and bondage, psychological and spiritual forms of slavery as well. The character Flo Hatfield is very much enslaved to desire and her hedonistic passions. The protagonist’s father, George Hawkins, is enslaved to his racial pain—he needs to keep stroking his lacerations in order to preserve his sense of identity. Metaphysics runs through this narrative. I wrote an introduction for the book, in which I talk about how hard it was to publish in 1980. It was rejected two dozen times. Nobody understood it. That book is 20 percent more complex than Middle Passage, and it made that sea adventure story possible since I worked out some of its narrative decisions and strategies in Ox. I’ve often called this my platform novel for two reasons: First, because if I couldn’t have written and published that book, I wouldn’t have written anything else. I wouldn’t have cared to write anything else. Everything I have published in the way of Buddhist-related literature has been built on the courage it took in the late ’70s to write that novel. Secondly, I call it my platform novel as an allusion to the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch.

NGN: Let me go a bit further concerning your position of not being a race writer. You have stated in the past that you are an artist who happens to be African American/black, thereby placing race as a secondary trait. Do you still adhere to that premise?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Yes and no. Let me put it this way. I am not blind to the experience of the illusion of race because I considered it to be a lived illusion, one that causes enormous suffering, but neither am I bound by it. I have written about race, but I am not bound by race. And, as a secondary trait, yes, I would say that. Really, I think race is a lived illusion. I think the scientists would agree with me on that as well.

NGN: You have suggested that you stay away from autobiographical connections in your fiction. Is Rutherford Calhoun, the protagonist of Middle Passage, in any way Charles Johnson?

CHARLES JOHNSON: All the characters in a book are you, because you have to bring them to life on the basis of your own life. I always tell people that I am a lot more like Rutherford’s brother, Jackson Calhoun, than I am Rutherford Calhoun. But I am every one of the characters in the book, obviously. That is how they came to be. You use what you might call an autobiographical detail, or data, from your life, but it is not like autobiographical writing, like a memoir. I consider my life to be pretty boring. I almost never talk about myself. Only if I’m asked to do so. I already know about myself so I don’t enjoy talking about me. I’d rather listen to other people and learn something I don’t already know.

NGN: Middle Passage recently had its twenty-fifth anniversary. It was an extraordinary feat of writing that is well acclaimed. I find it as much fun to read now as it was twenty-five years ago. I was among those who absolutely believed that the Allmuseri tribe was real. It is interesting how things change over time. The humor is still there but the specifics of the humor change. In the passage in which Rutherford is telling Squibb why he does not want to get married, Squibb says, “Oh, I know about wives all right. Got a couple myself—one in Connecticut, and one in Vermont.” I was not living in Vermont when I originally read Middle Passage; now I am living in Vermont, and that passage resonated with much more humor for me than it had before. Did you have a sense that you had your readers laughing with pure enjoyment when they read this?

CHARLES JOHNSON: There is humor because I think human beings can be humorous. That does not mean slavery is humorous. A character like Squibb is humorous. There are jokes in there—I deliberately put those jokes in the text.

NGN: You have stated that your aesthetic and intellectual approaches were different from James Baldwin’s. Would you expand on that?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Baldwin found a way to write short fiction and novels in a fairly naturalistic way. I am far more experimental with form and language than Baldwin is. I am trained as a Western philosopher—a phenomenologist—with a particular orientation towards literary aesthetics and Eastern philosophy, but I am not sure what his intellectual approach is. It is sort of Christian at times, because of his background as a child preacher, and it is very much in the mode of the Civil Rights Movement. Baldwin wrote an important, critical essay—“Everybody’s Protest Novel”—and then he turned around and wrote protest novels. The only thing I want to protest is ignorance in whatever form it takes.

NGN: Christianity has a mass appeal base for African Americans. Do you think more blacks should become Buddhists?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I do. I wrote an essay on that in Taming the Ox, called “Why Buddhism for Black America Now?” I think more Americans should become Buddhist. Remember: The Dharma is just wisdom. The Buddhist experience is just the human experience. It’s all about leading an examined life.

NGN: What has surprised you most in your long and exceptional career as an artist?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I was raised as a cradle Christian, and then Buddhism came later. What surprises me most is how well the Almighty has directed my life, better than I could have done. For example, I took a job here at the University of Washington because I needed a job. I had never been west of the Mississippi. I didn’t know anything about the West Coast at all. And this is where I have lived now for half of my life, since 1976. This was the perfect city for me. I would not have made that decision on my own to actively pursue a job on the West Coast. I’ve trusted God a lot since my teens, and still do. Like my dad, I say my prayers at night before pulling back the bed covers; my wife is a very Christian woman, as my parents were. I feel very blessed that something higher than myself has guided my life.

NGN: As you know, many of the philosophers you praise have also spoken rather harshly of blacks—claiming that they are inferior. How do you reconcile their position of blacks’ inferiority? David Hume is a perfect example.

CHARLES JOHNSON: Hume is to be believed when he analyzes the experience of the self. He is not to be believed when he talks about black people. He is not an authority on everything. He is not right about everything. So the question is, do you want to throw the baby out with the bathwater in every one of those cases? I don’t think you should throw the baby out, but I think you should throw out the stuff that is wrong—erroneous and junk. You are going to have to do that because you are going to find too many white, Western thinkers who have something negative to say about somebody of color. That does not take away from their scientific achievements. You have to separate those things out. When Hume and others who are racists talk about black people, they are wrong and they do not know what they are talking about.

NGN: Ultimately, what does the downfall of men such as Bill Cosby and O. J. Simpson mean for African Americans?

CHARLES JOHNSON: The fact is that we need positive images in popular culture of black men. And Cosby had provided that, we thought, for decades. For that to be diminished or dismantled because of his own foolishness and lust—it is painful. It is a black eye for black men. We are vilified and demonized enough in this culture, and it has been that way since the seventeenth century. It is something we always have to fight. We have to teach our male children, like my very smart grandson, to be strong and have confidence in themselves and know their worth. So when you hear stuff like this, Cosby and O. J. Simpson, it is just painful. They are not the first people to fail. White men fail all the time, too, but they are not demonized the way we are as a group.

NGN: Drug dealers, sex-workers, pimps, hustlers, and political revolutionaries are common in the books of Iceberg Slim, Chester Himes, Donald Goines, and others. What assessment do you place on that type of literature?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I had exposure to those authors when I was much younger, but I don’t have exposure to the characters they talk about: drug dealers, sex workers, pimps, and hustlers. I have no direct experience of that world. So, I don’t really pass judgment on it. I couldn’t write about characters like that because I don’t know them. Do young people know those writers?

NGN: Rather than some people picking up Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, or you, they somehow find themselves reading these writers. I don’t know how to explain that. These writers are still selling books.

CHARLES JOHNSON: I had a college friend who didn’t read much, but he at least knew about Pimp: The Story of My Life by Iceberg Slim. Among young black males who do not read, that is a book they know about, maybe just because of the title. I don’t know what to say; I think it is full of racial stereotypes. I think they give a negative impression of black males. I never taught them. How could I? They’re not literature.

NGN: I know students write papers for other students, but you are the first person I know who actually did it. I laugh when I think of it. Do you ever think that one of those papers you wrote for ten dollars for a student will show up on eBay?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Well, actually I think it was five bucks a paper, and it was a composition class. It was required. I had taken the class and so I already knew what was being taught. I said, give me your assignment, I will write it, and you can go out and party all night if you want to. You pay me five bucks; I guarantee an A for you. I never had to give back the money.

NGN: At one point, it was very common to come across book reviews in major publications by Charles Johnson—not so much anymore. Why not?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I made a decision after I’d published around sixty reviews that that would be enough. I could step away from book reviewing even though I had a strong motivation to engage other contemporary writers of my time. But people have dragged me back, like last year, I was asked to review Styron’s collected nonfiction. I said okay—I don’t know Styron well enough, so let me see what I can learn. In Taming the Ox, I talked in the preface about how I’m now entering the winter season in my life. Reviewing was something I did in my twenties through my fifties. At age sixty-eight, it’s more appropriate for me to devote my diminishing time on Earth to other things.

NGN: The Adventures of Emery Jones, Boy Science Wonder (2013) is a book you created with your daughter, Elisheba Johnson, for children. How is the father–daughter team different from Charles Johnson alone?

CHARLES JOHNSON: What is different is that I always listen to what my daughter says to me. If she says something, I do not contradict it. I do not change any writing that she does. And if I write something she objects to, I take it out. She’s much closer to how youngsters think than I am so I follow her lead. She has to be happy with it or it doesn’t happen, because she suggested the idea that we collaborate on children’s books.

NGN: You once remarked, many years ago in an interview in Callaloo (1978), that “The literary work of art is closer to the life of consciousness,” which suggests that, for you, writing is superior to drawing. Would you please expand on that statement?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Actually, it’s the other way around—a picture is worth a thousand words. In this sense, I’m very much like John Updike, who was a cartoonist, and said nothing he wrote was ever as satisfying to him as his drawings. When I came back to drawing in the 1990s, it was because I can never give that up. It’s a way of expressing myself and I’ve had a talent for it. Something that has always disappointed me about people in the literary world and in English departments is that our literary scholars do not have any background in the visual arts. They are trained in language: with literary works, novels, stories, and poems. They can’t really understand a part of me that is really important if they don’t understand what the visual arts mean to me. And what the visual arts have meant to many writers—D. H. Lawrence, William Blake, Tennessee Williams, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Clarence Major, and so many others. There is a wonderful book I strongly suggest you look at, The Writer’s Brush: Drawings, Paintings, and Sculpture, edited by Donald Friedman. You’d be surprised by which writers are in that book.

Sartre has a memorable phenomenological description of what happens during the reading experience in What Is Literature? Open any novel, start reading any short story. What is there? Black marks—signs—on white paper. First, they are silent. They are lifeless marks, lacking signification until the consciousness of the reader imbues them with meaning, allowing a fictitious character like Huckleberry Finn, for example, to emerge from the monotonous rows of ebony type. Once this magical act takes place in the mind of the reader, an entire world appears in consciousness: “a vivid and continuous dream,” as novelist John Gardner once called it, one that so ensorcels us that we forget the room we’re sitting in or fail to hear the telephone ring. In other words, the world experienced within any book is transcendent. It exists for consciousness alone. To bring that literary world into being requires, Sartre observed, the “conjoint effort of author and reader.” While the writer creates this world in words, his or her work requires an attentive reader who will “put himself from the very beginning and almost without a guide at the height of this silence” of signs. Reading then is directed creation. For each book—each novel or story—requires that a reader exercise his freedom for the “world” and theater of meaning embodied on its pages to be. As readers, we invest the cold signs on the pages of Wright’s Native Son with our own emotions, our own understanding of poverty, oppression, and fear. Then, in what is almost an act of thaumaturgy, the powerful figures and tropes Wright has created reward us richly by returning our subjective feelings to us transformed, refined, and alchemized into a new vision with the capacity to change our lives forever. But when you look at these paintings in this room, for instance, that is a different aesthetic experience. You don’t have black marks on white paper. What you have are color and form that you instinctively without language recognize as a woman, a man, or a still life. This is a universal experience, one not based on language, because we think in terms of pictures. The oldest drawings we have—those beautiful images of bison in a cave in France—transcend language, that is, you can be a French speaker, or a German one, but you’ll instantly recognize these figures as bison. The experience of visual art is . . . well, more fundamental than the experience of reading. In my life, my heroes were first visual artists and then philosophers. When I was a teenager I used to think to myself, “Man, this person can create beauty!” And I concluded that “Artists must be the happiest people in the whole world, because look what they can do.” Then, later in life, I started to meet writers and artists, and discovered that they were for one reason or another the unhappiest, or most dissatisfied, people you can ever meet, like my high school art teacher. But I still believe, at age sixty-eight, that if you can create beauty, what more do you want out of life?