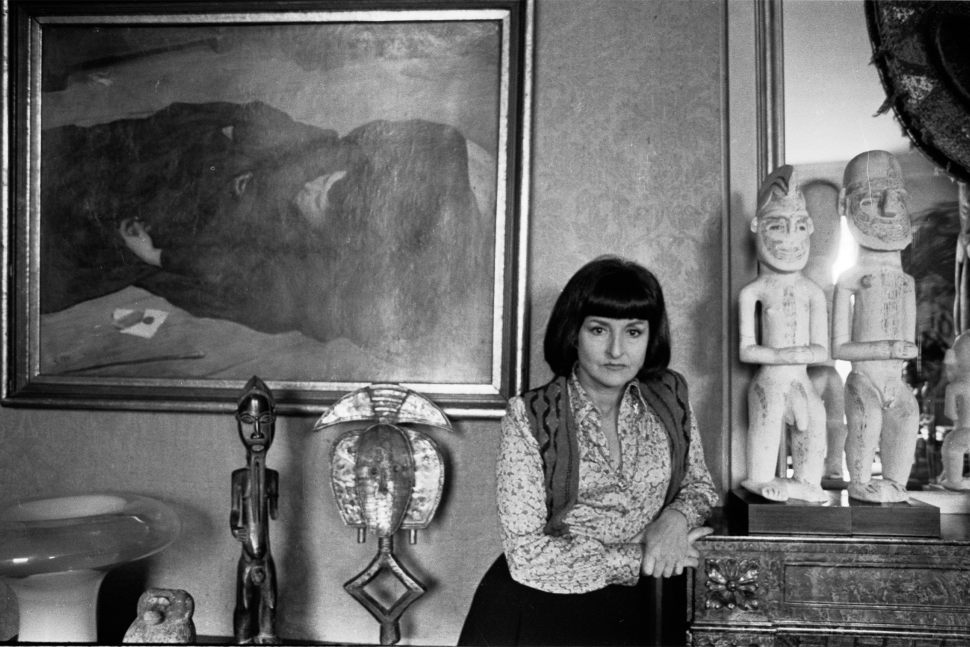

Left: Joyce Mansour courtesy of Marion Kalter. Right: C. Francis Fisher.

Poet Sarah Wolfson talks with NER 44.4 translator C. Francis Fisher about the historical impetus for surrealism, translating lines rather than words, and the dreamlike logic of Joyce Mansour’s poetry.

Sarah Wolfson: What do you remember about the moment you discovered Mansour’s work? What made you want to translate it?

C. Francis Fisher: I first came across Joyce Mansour in English translation. During the second year of my MFA, I was in an Avant-Garde Poetics class taught by Alan Gilbert at Columbia University and we read a selection of her poems from Poems for the Millennium (a wonderful anthology put together by Pierre Joris and Jerome Rothenberg) translated by Mary Ann Caws.

Right away, I was floored by Mansour’s directness, eroticism, and willingness to transgress taboo. The same day, I went to the library and took out every book of hers they had in French. The joy I get from reading her work—the beautiful and shocking images, a femininity that defies norms, some ineffable unruliness that feels true to my experience of life itself—is the same reason I want to translate it: so more people have the pleasure of reading it.

SW: What brought you to literary translation in the first place?

CFF: I was lucky enough to learn French in elementary school. Having always been one for escape and living in my own head, learning a new language gave me twice the space to explore my own imagination. I was quite nerdy, and while my classmates were saying they wanted to be veterinarians and firefighters, I told everyone I wanted to be a translator.

That idea was always there in the back of my head but became subsumed in adolescence by the desire to be a writer. Then, during my MFA at Columbia which I attended in part because of their translation program, I met several wonderful teachers—Bela Shayevich, Susan Bernofsky, Katrina Dodson, and Matvei Yankelevich—who dispelled the smoke and mirrors that sometimes hang around the artform and made literary translation seem like a real possibility.

SW: Mansour seems to have been under-appreciated outside the domain of French surrealism, despite her importance within it. What do you hope English language audiences will take from her work?

CFF: It is my hope that English language audiences have the experience I have with Mansour: that of reading something that reanimates life and estranges it; as something that makes the stone stonier as Viktor Shklovsky famously said.

In addition to this, which I think can be true of all great literature, there is the fact that Mansour tears women from the pedestal misogyny can relegate them to. She insists that women have the ability to be just as sexually promiscuous or just as violent as men—that they are not simply the fairer sex, the benevolent mother, or the caring wife. This dark side to equality is as important to remember as the more palatable fact that women are as smart and capable as men.

Lastly, I will acknowledge a personal belief: that all writing and translating is political. As such, we have to contend with the original historical backdrop of Surrealism—the fascism of 20th century Europe. It might not surprise readers that the movement is having a revival during our similarly turbulent times. The power of dreaming another world, not as escapism but rather as the first step to actualizing such as place, is not lost on me. I hope that English readers will imagine a new world alongside Mansour and my translations.

SW: Tell me about your translation process. What tools do you use or avoid? Is there a particular element of craft or style that you look at first?

CFF: Translation begins in reading—sometimes I consider translations the most careful and loving readings of a given text. As such, I begin by reading a text and writing about my experience of it in the original language; where did my mind go? What were my emotional responses? This helps later as I try to capture the affect of the poem that might exist not exactly beyond language itself but alongside it.

For poetry in particular, I avoid word by word translations and focus instead on translating entire lines. This helps get away from overly literal translations and allows me to maintain elements like sound and sense.

My favorite tool when translating is the thesaurus. I use an old-fashioned paper edition because I have to turn off my WiFi while I work since I am endlessly distractable.

SW: What was the biggest challenge you faced in bringing these three poems into English?

CFF: Like in any translation there were hundreds of tiny frustrations and pleasures in bringing these three poems into English. The French are lucky enough to have the verb éteindre which Mansour makes liberal use of in “Friends’ Eyes.” It translates in a number of ways but the sense in this poem is to extinguish. However, one does not typically, in English, extinguish their cigar as this is far too rarified for the equivalent French phrase so I translated it as to “put out” one’s cigar. The lack of an elegant solution, the replacement of one word for two, frustrated me endlessly but was clearly the right choice.

I share this to illustrate the myriad of choices all translators constantly make. My biggest challenge, however, was the phrase “the Grand Tetanus” in “Fragment of a Call.” It was not a challenge in the sense of being difficult to translate but rather because I had trouble understanding its importance in the poem. Throughout Mansour’s work there are moments of opacity, times when I do not follow her references or dreamlike logic. This was one of them and in my time working with her poems moments like this have given me the greatest anxiety as a translator. Still, they remind me time and again that literature exists at the boundaries of apprehension, that there will always be something outside of our knowledge and understanding and I have tried to come to terms with this essential wildness of texts themselves.

SW: The poem “Fragment of a Call” ends with the lines “And somewhere in the future / A drunkard named Duty / Vomits.” Walk me through the poetic choices you faced in translating those lines.

CFF: The first choice I made had to do with the word “future”. In French, Mansour chooses the word lointain which translates literally to distant and can be used to denote both time and space—as in something is physically distant or temporally distant. Since she refers to a waiting room and a confused temporality in previous lines, I chose to translate it in reference to time. Once that decision was made, I had to decide what the timeline should be in accordance with how I read or understand the poem. There seems to be an unexpected optimism to the poem—the desire to communicate despite potential shortcomings in such lines as “What to write to you” or “My misconstrued phrases in their satin shoes.” Optimism is always oriented towards a potential future, something yet to come. So lointain became future.

This was the most complicated choice I made in the lines above. The other was something that plagues all translators of Romance languages: do I stick with the Latinate English translation or do I try something more Germanic? In other words, should the final line, Vomit in the French, remain so in English or should I make it “throws up”? I went back and forth on this question but in the end decided “throws up” sounded too crass for a poem which calls a drunkard Duty.

SW: “Rule of Life” is one of those poems that channels a universal feeling through an intense blend of brevity and specificity. Is there a particular image or moment around which your translation of that poem hinged?

CFF: For me, the poem hinges on its penultimate line: “Feed to keep others.” The reason for this lies in the fact that Mansour uses the verb manger (which I translate as eat) throughout the poem until this line where she writes instead se nourrir (which I translate as feed).

In an earlier draft, I had translated both manger and se nourrir both as eat because I was lacking an elegant way to render se nourrir since my first instinct “nourish yourself to keep others” felt clunky and overly intellectual. A colleague suggested feed and by making this change the translation came into sharper focus. For me, the poem hinges on this line by showing the animalistic way humans fight to stay alive.

SW: When you’re translating, how much do you hope to assimilate a poem fully into English versus highlight distinctive linguistic and/or cultural values of French?

CFF: Translators sometimes obsess over the quandary of domestication and foreignization and your question certainly brings this anxiety to the fore. The former approach may assimilate a text in a way that erases difference, whereas the latter risks exoticizing the otherness of the original. While translating Mansour, I faced difficult choices in regard to these two poles. For example, in a poem from the forthcoming book which wasn’t published here, Mansour uses the word Béni-oui-oui. This phrase was a derogatory term for Muslims who collaborated with colonial authorities during French rule in North Africa, especially in Algeria and Morocco. Although my translation of the term (“yes-men”) may elide this important history, I felt that leaving the original French phrase in italics would speak only to an exclusive readership. The poem’s intention, it seems to me, is not to narrow the audience, which can be read more broadly as a poem against totalitarianism. Translations are always new readings of a poem, incapable as they are of being a facsimile of the original, and as such they have to respond to what the translator imagines as the tone of the work. This is true in all choices including those that invoke the potential assimilation or over distinction of difference.

There is a larger sense in which this quandary occupied me throughout working with Mansour: I was faced with whether to assimilate or foreignize Mansour’s very thought. Surrealism’s investment in free-association is notorious. In translating Mansour, I had to interpret her dreamlike association well enough to translate a coherent poem—a sort of domestication—but also leave the unruliness intact.

SW: How did you go about choosing poems for the forthcoming book In the Glittering Maw: Selected Poems of Joyce Mansour? Which, if any, coherent threads you did you hope to communicate in your choice of poems?

CFF: I was focused on Mansour’s later works in this volume because they have been translated into English the least. Her early poems are quite short and punctuated. Later, the work grows more riotously, taking up pages and eschewing punctuation all together. It was these late poems that I wanted to give English readers a window into with my translations.

SW: You’re a poet yourself. How has translating Mansour’s work impacted your own?

CFF: I love this question! I think about this all the time because in many ways we are very different poets. My own work is most indebted to two traditions of poetry: the New York School’s love of the quotidian, and the objectivist’s eye. As these affinities suggest, my poetry is far more invested in waking life than the space of dream. Still, I’ve taken Mansour on as an interlocutor. I imagine her asking me why I feel the pressure to be legible or coherent. She occupies my mind and I talk to her sometimes when I’m writing. Recently, I’ve been lifting favorite lines of hers (or are they mine now if they’re in English? more likely they are a collaboration with the dead) and using them as first lines in my own poems. I love experiments and translation has come to feel like an endless prompt.

Sarah Wolfson, a former staff reader for NER, is the author of A Common Name for Everything, which won the A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry from the Quebec Writers’ Federation. Her poems have appeared in Canadian and American journals including the Walrus, TriQuarterly, the Fiddlehead, AGNI, and Michigan Quarterly Review. Originally from Vermont, she now lives in Montreal, where she teaches writing at McGill University.

C. Francis Fisher is a poet and translator who received her MFA from Columbia University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Brooklyn Rail, New England Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books among others. Her poem “Self-Portrait at 25” won the 2021 Academy of American Poets Prize. She has been supported by fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and Brooklyn Poets. Her first book of translations, In the Glittering Maw: Selected Poems of Joyce Mansour, is forthcoming in May 2024 with World Poetry.