It’s 1973 and they’re young and newly married. They grew up in the same small town in Georgia. He’s seen a little bit of the world—Tennessee, Alabama, and—framed by airplane windows—Alaska, Mt. Fuji, and the Philippines. He has Polaroids of these places that he mailed in letters to his momma, sisters, and wife while he was away—show them a very little of what he’d seen. There’s been a war going on, and he enlisted before they could draft him and tell him where to go.

When he comes back home to Georgia, on leave to visit family and pick up his wife for the long drive back to Fort Lewis in Washington state, they learn quickly to wake him slowly. Though he doesn’t much talk about it, he does say it wasn’t as bad for him as some of his buddies. He’d kept helicopters airworthy over there. He and his wife, they drive across the country in his ’65 Chevy Chevelle SS four-speed—American muscle. They take the southern route—through Texas out to California and up the coast to Washington—and they see more of America on this trip than most in their families have seen or will see in their lives.

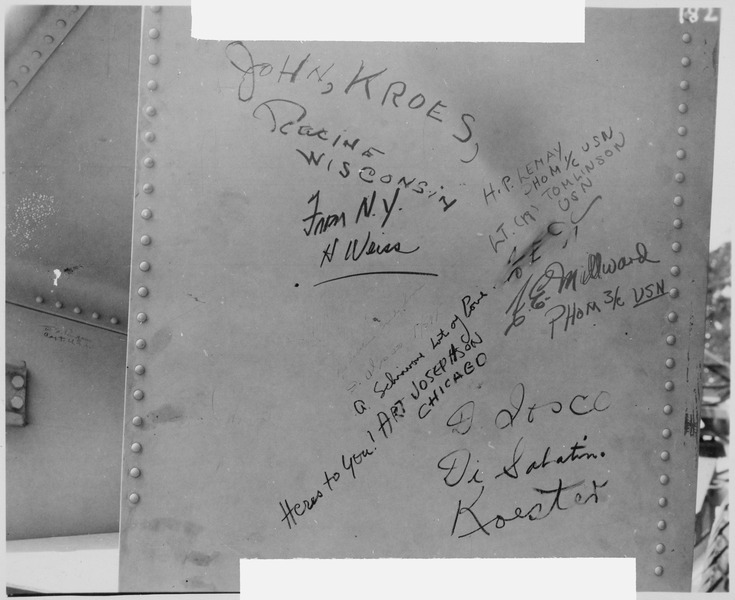

This morning, as they check out of the motel in Flagstaff, a postcard catches his eye. He points it out to her. What looks to be an old English village with a towering bridge behind it and mountains in the distance behind that. They read the fancy script: London Bridge Lake Havasu City, Arizona. And she wants to see it; it’s only twenty miles out of the way. He wants to see it too. What’s the bridge doing here?

A rich businessman and land developer, looking to build an oasis in the desert, bought it from the City of London two years before—had it taken apart, the pieces carefully numbered and brought to Arizona to be put back together on a peninsula in a new manmade lake on the Colorado River. The land was dug from beneath the bridge to let water flow and create an island—a reason to cross the bridge—a destination in this landscape of sand and buttes. Take an old stone bridge and seed a new desert vision. A bit of out-of-place past to build the future in this country to prove anything’s possible.

They have dreams and will soon have a family of their own. It’s 1973 and it matters, but matters differently every day, that they’re Black and the rich businessman is white—things seem to be getting better.

*

Secret Americas features writing about images from the U.S. National Archives.

Image via Flickr – “London Bridge–brought from London to Lake Havasu City in 1971, May 1972,” photograph by Charles O’Rear. National Archives and Records Administration College Park.

Sean Hill’s first book, Blood Ties & Brown Liquor, was published by the University of Georgia Press in 2008. His second collection of poetry, Dangerous Goods, is forthcoming from Milkweed Editions in early 2014. He’s currently a visiting assistant professor in the creative writing program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. More information can be found at www.seanhillpoetry.com.