Nonfiction Editor J. M. Tyree interviews Lou Mathews about his new book, Shaky Town, taking a sidelong look at LA and suggesting that “laughter is the only reasonable response to a hopeless position.”

The stories Lou Mathews has contributed to NER over the years often take up the dark underbelly of Hollywood, in which writers live on scraps from the studio system. They tell hilarious but heartbreaking stories of not making it big in La La Land. In “Tutorial” (41.2) an adjunct screenwriting prof attends an awards ceremony for a rich ex-student at a Malibu college campus from which he himself had been banned. His “Some Animals Are More Equal than Others” (35.2) transpires amidst the madness of a disastrous location shoot in Nicaragua that sometimes resembles a cross between Alex Cox’s Walker and Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo.

Lou has also tirelessly aided other writers throughout his career as a creative writing teacher and mentor, and has sent many writers our way, including Kate Kaplan (39.1), Ella Martinson Gorham (39.4), Chelika Yapa (37.3), Marilyn Manolakas (40.4), and Emily Hunt Kivel (41.4), some of whose stories were selected for Best Americans and Pushcart Prizes. He also hosted and helped arrange our first-ever Los Angeles reading, in 2014 (photos here). And his red enchilada sauce, jars of which are highly sought after in the NER offices, is a joyful elixir.

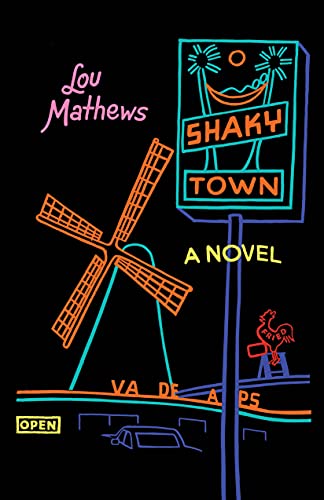

I caught up with Lou after reading an advance copy of his new book, Shaky Town, from Tiger Van Books. Lou’s interconnected stories here delve into the complexities of working-class LA, exploring the lives and worlds of teachers, shopkeepers, Lorca-loving janitors, and retired park-bench storytellers.

In the moving “A Curse on Chavez Ravine,” the narrator relates the story of his Aunt Lupe’s one-woman battle against the redevelopment of her neighborhood to make way for Dodger Stadium. After going to court and chaining herself to her house during the demolition, she commissions a spell to be placed on the players that will last for generations.

The story is characteristic of Mathews’s wry, compassionate, and deeply felt writing, but it stands as much more than a local rebuke to the film-industry version of Los Angeles promoted by that company town. His refreshing vision is ultimately restorative and recuperative of a different image-bank entirely, by avoiding much mention of Hollywood at all.

JMT: The interconnected stories in Shaky Town explore a more real LA. Hollywood really only appears as the location of the DMV and a liquor store, I think! Here, you’re focused on working people and communities of color. How do you meld your personal and artistic connections to your material?

LM: These stories are personal. As Carolyn Chute once said, of writing The Beans of Egypt, Maine, “this book was involuntarily researched.” That’s the best way I know to explain Shaky Town. That neighborhood was where I grew up, and how I grew up. Nobody was writing about my family, my neighbors, my classmates, where we lived and how we lived. We were not considered suitable material for literature. I didn’t learn that until later, so I wrote the stories.

I also didn’t understand that we were poor, and that was one of the benefits of growing up in southern California. My mother was a widow, raising five boys on a Catholic school teacher’s salary, but when you lived most of your life outside, and the city you lived in had great parks and libraries, it didn’t register in the way it would if you were living in Chicago, ten floors up with a broken elevator. Years later, I read an essay by Albert Camus, on growing up in Oran. He wrote about the sun, the beach, the waves, the water. Those cost nothing. “I lived in destitution,” Camus said, “ but also in a kind of sensual delight.”

JMT: I think my favorite section of the book is about Aunt Lupe’s “curse” on the Dodgers as a result of having been evicted to make way for the building of the baseball stadium. I sense that hidden history—the violence inflicted on people and the land—lies at the heart of the book. But also a sense of potential recuperation through memory and storytelling. What do you think all this says about the city, the Golden State, and (for lack of a better shorthand) American dreams of various kinds?

LM: Most religions, political systems, and personal philosophies can be reduced to a single concept: Some day my prince will come. Your talents will be recognized. Movies, TV, advertising, our historical myths feed this dream. After a while you figure out that not only is there no prince, but if he did exist, he wouldn’t give you or yours a second glance. I think storytelling is the only way that the working poor, the landless, taxpayers but not participants, the voiceless, ever get to win. That’s probably why storytelling has a long history among all peoples.

The story of “A Curse on Chavez Ravine” started with a tale from one of my brothers’ padrinas (godmothers), something she’d heard from a friend in Chavez Ravine. Was it true? Probably not, but we wanted it to be.

JMT: Is there a film of LA that called to you while writing this book, or did you feel more defiant towards Tinseltown? I thought of Charles Burnett and Sean Baker, and their films in which the characters struggle to make ends meet and the city is itself a character in the story as well as an oppressive setting that is liable to tragic outcomes…

LM: This city isn’t only about the movies and the manufacture of myths, but if you live in Los Angeles, movies are always in the background. One of the characters in Shaky Town, Emiliano Gonzalez, the self-proclaimed Mayor of Shaky Town, worked for the studios as a skilled carpenter, building balsa wood chairs for John Wayne to break over other actors’ heads. That’s as close as most Angelenos get to the actual business of movie-making.

That said, there are a ton of movies that inform and coincide with my vision of Los Angeles. Like White Heat, with Jimmy Cagney’s transcendent epitaph: “Top of the world, Ma!” Every movie that Charles Burnett has made, but particularly Killer of Sheep. The Exiles (1961), directed by Kent Mackenzie, about the Navajo community living near Bunker Hill, is remarkable. Absolutely uncompromising, gritty, and sad, its uncomfortable honesty has always been a model for me.

Then there is a movie that no one knows by one of my neighbors, Ben Maddow, The Savage Eye. Ben was a blacklisted screenwriter, he did around ten movies using fronts. He’s best known for Asphalt Jungle and Intruder in the Dust. The Savage Eye was a personal project, a movie made over three or four years. It catches downtown LA and its denizens in a way that no one else ever did.

The other movie that needs to be mentioned is Alex Cox’s Repo Man, the only movie to make every top-ten list of movies made about LA. It’s there for a reason. It catches the humor and spirit of the place and focuses on the east side. It’s one of the few times I got to see the places and people I grew up with in the foreground of a movie.

JMT: Speaking of Repo Man, your stories for NER and in this new book share in common the poignancy of living in LA, this supposed paradise where life is ever so slightly less glamorous than advertised. How do you see the role of laughter in coping with the various nightmares of history, family, work, and relationships?

LM: Over the course of his life, Rembrandt painted numerous self-portraits, each one with increasing age demonstrating increasing dignity. Then, shortly before his death, in his final portrait, he shows himself stripped of finery and laughing. Laughter is the only reasonable response to a hopeless position.

Somewhere in his essays, Camus quotes an old Spanish proverb—something to the effect that, if it is nothing that awaits us, let us so act that it is an unjust fate. Laughter is a way to do that. An act of defiance.

JMT: There’s a long novella-like section, from which the book gets its title, devoted to the story of an alcoholic Catholic high school teacher who goes totally off the rails. Your compassion towards your characters doesn’t save them from facing the abyss, but it does evoke a necessary hope that change is possible, however unlikely or implausible. Do I read that right?

LM: “Shaky Town,” the novella devoted to Brother Cyril, a man who has lost his faith when he realizes that the church he has served for decades is covering up the sexual abuse of children, was the hardest part of the book to write. The last section took me more than three years, because I was convinced that Cyril had to die, at his own hand. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t kill him. When I finally understood that he didn’t have to die, that he understood that he had touched bottom and that some hope might be forthcoming, the last chapter wrote itself in a couple of days.

One reader, my friend Carter Wilson (Crazy February, Treasures on Earth, The Times of Harvey Milk), has compared Cyril to the Consul in Under the Volcano, a character for whom you should have no sympathy: “I was reminded strongly of Under the Volcano, the palpable misery in the still active mind—the mind that won’t shut up —and how we come to care about the fate of Cyril, the way we care about the Consul too.”

I’m not an optimist. But to the extent that we can recognize each other’s humanity, there’s hope. I think any hope on that basis is being tested in the world we live in now, but maybe I’m optimistic on that score and maybe the stories reflect that.

Lou Mathews has written seven books and published two of them, Just Like James and L.A. Breakdown, an LA Times Best Book. He has taught in UCLA Extension’s acclaimed creative writing program since 1989. His stories have been published in ZYZZYVA, New England Review, Short Story, Black Clock , Paperback L.A., and many fiction anthologies. Mathews is also a journalist, playwright, and passionate cook, as well as a former mechanic, street racer, and restaurant critic. He has received a Pushcart Prize and a Katherine Anne Porter Prize, as well as California Arts Commission and NEA Fiction fellowships, and is a recipient of the UCLA Extension Teacher of the Year and Outstanding Instructor awards.

J. M. Tyree is a nonfiction editor at NER, a contributing editor at Film Quarterly, and teaches at VCUarts. He is the coauthor of Our Secret Life in the Movies (with Michael McGriff), an NPR Best Books selection, and BFI Film Classics: The Big Lebowski (with Ben Walters). He is the author of BFI Film Classics: Salesman, Vanishing Streets – Journeys in London, and The Counterforce, from Fiction Advocate.