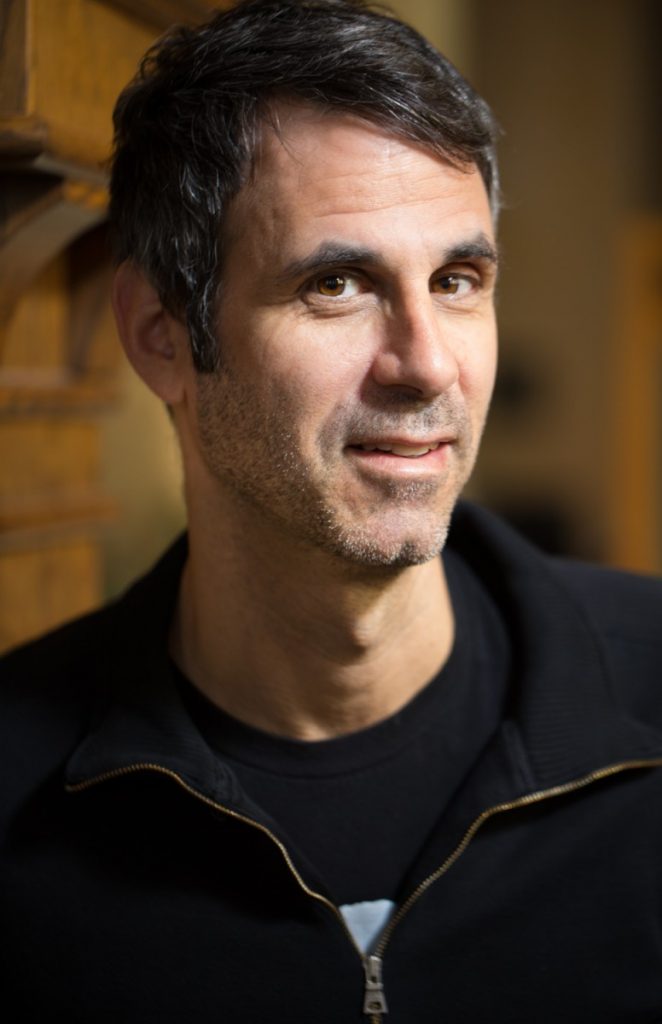

Steve Almond has been publishing fiction in New England Review since 2000. He spoke with editorial panelist Evgeniya Dame about his new story “How Can You Be Happy?” which appears in NER 40.2, and about the never-ending writer’s quest for “ecstatic bewilderment.” Read on.

Evgeniya Dame: The state of happiness is rare in literary short stories. When did you decide to lead Craig, your main character, toward a happy moment?

Steve Almond: Oh gosh. He’d suffered enough. The guy needed some joy. That’s part of the point of the story. We walk around in this culture telling ourselves that we’re after contentment and bliss. But that’s basically a crock. What we’re after, more often, is the feeling of being alive in the ways that are most familiar to us from childhood. Craig gets into an unhappy marriage and struggles to be happy because he saw and absorbed that growing up. I do get that most literature focuses on moments of anguish or trauma or sorrow, because those feelings are unresolved. They stick around. Happiness doesn’t have to explain itself. But it’s a part of the human arrangement, too, and I wanted Craig to get a taste of it. He’d earned it, I felt. Not because he’d suffered, but because he’d made some effort to understand the nature of his suffering.

ED: The punishment Trent chooses for his father—relegating him to the neutral pronoun It—seemed unexpectedly cruel, terrifying, and also logical. Once I read it, I couldn’t believe I’d never heard of this form of insult before. What gave you the idea?

SA: A friend of mine went through something like this, being reduced to an It, and I couldn’t get it out of my head. I felt so awful for the guy, and for his son, who was clearly in pain as well. As a dad I was like, “Omigod. That is the worst sort of insult. To have your personhood annihilated by your own child.”

ED: Your narrative style maintains such a perfect balance of compassion and detachment. We are close to Craig to feel the pain of his failing marriage and disastrous relationship with his son, yet not so close that we don’t wonder occasionally: maybe it’s his own fault. How do you regulate your narrative, especially point of view, to achieve this effect?

SA: Hmmm. I’m glad to hear I do this regulating, but not sure how I do it. I’m just trying to pay attention to Craig’s experience and to present all that he’s up against, all that he’s trying to do, but also not to let him bullshit me. That’s how you have to be with all your characters: ruthless and tender. Nobody’s a villain or a hero. We’re all some vexing mixture of the two.

ED: It’s interesting to think of your relationship with characters in such terms. How does it work with someone like Trent, who isn’t trying to be likeable? Have you ever come up with characters who did try to bullshit you, or who proved challenging otherwise?

SA: Trent makes himself tough to love because he’s in a lot of pain. That sentence applies to every human being on earth. I’m with Claire Messud on this: we don’t go to literature to make friends. We go there to encounter characters who are alive in the same screwed up ways we are. Honestly, the reader isn’t interested in our good habits of thought and feeling. They want to know that they’re not alone in their woundedness. As for characters who bullshit me . . . yes, of course. But the catch is that you can’t really bullshit a bullshitter. Or, to put it more bluntly: we’re all bullshitters and therefore unreliable narrators.

ED: I find your story endings . . . majestic. They remind me of bridges in songs, when the melody suddenly lifts off, except that your endings have truth to them and are both inescapable and unpredictable. What’s your process for writing a story ending?

SA: I’m so glad to hear this! I really worried that the ending was flat. I think most writers struggle with endings, because we feel that we have to really “stick the landing” and that self-consciousness makes us push around the language. With this story, I just wanted to grant Craig a moment of clemency, self-forgiveness, the pursuit of an innocent pleasure.

ED: So, how do you know when the ending is right?

SA: You don’t. I often write right past the ending. Or I get that performance anxiety and overwrite the thing. What I do know is that a good ending should stay with the reader, even haunt them if possible. I’m thinking about the last paragraph of the short story “Guests of the Nation” by Frank O’Connor. That final burst of language and feeling has stayed with me for decades.

ED: You mentioned elsewhere attending many readings when you first moved to Boston. Could you speak of one or two that left the most impression?

SA: That’s a tough one. I’ve seen hundreds. I especially loved the poets, honestly. They read at Blacksmith House—my pal Camille Dungy, Frank Bidart, Louise Gluck, Robert Pinsky, Thomas Lux, Tony Hoagland. Such intensity. It was like being drunk on language, on feeling.

ED: I love Tony Hoagland! I recently finished “What Narcissism Means to Me.” How did reading and listening to poetry influence your writing?

SA: I think it just hammered home the idea that courage and efficiency are what matter. Poets strip down and spring-load the language. They get rid of all the extra words. And they celebrate the ecstatic and bewildering. That’s what I’m always aiming for: ecstatic bewilderment.

ED: Your favorite thing to do when not writing?

SA: Hanging out with my kids (even when I’m reduced to an It).

***

Steve Almond’s most recent book, William Stoner and the Battle for the Inner Life, is about the novel Stoner by John Williams, as well as “reading and writing and the struggle to pay attention to our lives.” He is also the author of God Bless America (Lookout Press, 2011), The Evil B. B. Chow (Algonquin, 2005), and My Life in Heavy Metal (Grove Press, 2002). For more information please visit his website stevealmondjoy.org.