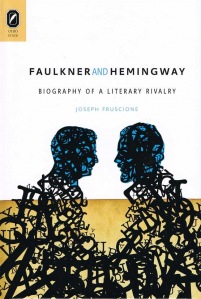

Faulkner vs. Hemingway | By Joseph Fruscione

It took me until 1998, when I went to graduate school, to begin to appreciate Hemingway. In my junior year of high school, I couldn’t finish The Old Man and the Sea soon enough. In my senior year of college, I couldn’t finish The Nick Adams Stories soon enough. Yet his collection In Our Time—specifically the opening piece of the 1930 edition, “On the Quai at Smyrna”—hooked me. I remember reading it while waiting for a Metro train outside DC. Twice, in fact. It was probably a combination of being a little older, starting a doctoral program, and reading such indelible descriptions of the chaos of refugees evacuating Smyrna that finally helped me “get” Hemingway, particularly this kind of writing from the last paragraph:

When they evacuated they had all their baggage animals they couldn’t take off with them so they just broke their forelegs and dumped them into the shallow water. All those mules with their forelegs broken pushed over into the shallow water. It was all a pleasant business. My word yes a most pleasant business.

Wounded mules, scared refugees, repeated they pronouns, no commas—all of this resonated with me in a way Hemingway never had before.

It was different with Faulkner: I’ve never not liked his work. It started in my junior year of college with his story, “The Old People,” which I was reading in a course on Magical Realism. The first time I read it, I marked this opening passage:

At first there was nothing. Then there was the faint, cold, steady rain, the gray and constant light of the late November dawn, with the voices of the hounds converging somewhere in it and toward them. Then Sam Fathers, standing just behind the boy as he had been standing when the boy shot his first running rabbit with his first gun and almost with the first load it ever carried, touched his shoulder and began to shake, not with any cold.

I’ve never hunted and likely never will. Yet, such writing—with its clear imagery, many commas, and the evocation of Isaac McCaslin’s wilderness initiation—grabbed me. I then spent the 18–19 months between college and graduate school reading a lot of Faulkner’s work—primarily his novels, but most of his Collected Stories as well.

Perhaps the richest part of the writing process involved in my book on these two writers was the week in summer 2003 I spent working with Hemingway’s unpublished correspondence at the Kennedy Library in Boston. I read through folders upon folders of his letters looking for references to Faulkner, noting throughout how complex (and sometimes misunderstood) a personality Hemingway’s was. As I delved later into Hemingway’s career, I struggled more to read his handwriting and edits, all indications of his increasing mental struggles. The writer of many of these letters was highly emotional, anxious, and insecure—a person very different from the macho, worldly image he helped promote.

The most consistently revisited moment of my study is April–July 1947. Hemingway, Faulkner had noted in comments at the University of Mississippi, lacked sufficient courage as a writer to experiment. Faulkner, Hemingway thought when he got wind of this a month later, was off base and needed to be presented with conclusive evidence of his battlefield composure (in the forms of a letter from General Charles Lanham and a copy of Hemingway’s Bronze Star citation). The authors returned to this moment often: in the letters they wrote to each other that summer, in later correspondence with others, and in their public remarks. The charge nettled Hemingway, and in his fiction and letters he often returned his own (humorous) criticisms of Faulkner’s drinking and excess experimentation—such as in his observation about Faulkner’s “boozy courage of corn whiskey” (redefining the “courage” charge). “When I read Faulkner,” he wrote to Harvey Breit in 1952, “I can tell when he gets tired and does it on corn just as I used to be able to tell when Scott would hit it, beginning with Tender Is The Night.” (Fitzgerald, dead nearly twelve years by this time, continued to figure frequently in Hemingway’s thoughts.)

Faulkner’s observation qua appraisal of Hemingway’s courage to experiment as a writer also showed me something significant about Faulkner: he was always more private and reserved, and he felt himself superior to his contemporaries. He never retracted his assessment. Even when he ostensibly apologized for the remark, he sounded a note of one-upmanship, such as in his observation in a 1957 Vogue interview that Hemingway’s controlled “method” meant he “wasn’t driven by his private demon to waste himself in trying to do more than that.” Yet Faulkner remained preoccupied with Hemingway for crucial decades of his career, perhaps feeling a conflicted sense of camaraderie as well as competition.

Each time I return to this episode—which led to the only located correspondence between them—it’s shown me the psychological hold these authors had over one another. In their rivalry, they shaped and influenced each other more than either was ever willing to admit.

*

NER Digital is a creative writing series for the web. Joseph Fruscione is adjunct professor of English at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and an adjunct assistant professor of First-Year Writing at George Washington University. His first book, Faulkner and Hemingway: Biography of a Literary Rivalry, was published in January 2012. He has also taught Faulkner-themed classes at Politics & Prose, an independent bookstore in Washington, DC. He lives in Silver Spring, MD.