Lunar Mist: Notes on Tommaso Landolfi by Nicholas Benson

There is often the greatest pleasure in reading those authors whose stories defy our attempts at definition or description. Why dispel that luxurious confusion? This is underscored if you’re recommending a book to someone else. Even the barest summary might deprive the potential next reader the privilege of experiencing the book for the first time. What does a friend do when he wants you to read something? He hands you the book and freaks out a little bit, maybe gives you an idea of the weather of the book, says “you gotta read it” with a manic look in his eyes. The reader has crossed over and become possessed by the story.

This reader’s exalted state also belongs to many of Tommaso Landolfi’s characters. His stories begin with a paradoxical excitement, the narrators appearing to simultaneously crave and dread their appointed role.

“Nearly all of Landolfi’s characters are a little maniacal, hysterical or unhinged,” Pietro Pancrazi wrote in 1937. Among the eccentric geniuses of Italian literature, Landolfi (1908-1979) was renowned for preferring gambling casinos to literary society. His degree was in Russian literature (thesis on Akhmatova), and he translated from the Russian and German. His characters seem to have stepped out of the pages of Dostoevsky or Poe, as narrated by Kafka or Gogol. In the small, black-and-white author photo, he’s a haunted version of Dostoevsky’s Alexei from The Gambler, still blissfully, terrifyingly unable to rise from the croupier’s table, a century later. But this nocturnal misanthrope was in fact a prolific author, a virtuoso with a penchant for ventriloquism, with a great many literary friends — including the Florentine critic Carlo Bo, whose dictum “letteratura come vita” (literature as life) Landolfi would respond to in Rien va, one of his three memoirs, with the equally succinct motto “la letteratura non è vita” — literature is not life.

In Landolfi’s story “Dialogo dei massimi sistemi” (“Dialogue of the Greater Systems”), that is more or less what the ostentatious academic character, a hilarious parody of Benedetto Croce, has to say to two suppliants, of whom one is the narrator. “Dialogue of the Greater Systems,” the titular story of Landolfi’s 1937 debut, is an ambiguous parable in which literary solipsism is celebrated, indicted, and (unconvincingly) shrugged off as another droll prank of life and language. The title refers to Galileo’s heretical Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), in which the astronomer compared the Ptolemaic and Copernican models of the solar system. Galileo’s original title for his forbidden work, Dialogue on the Tides, hints at Landolfi’s own predilection for characters that are ebbing and flowing with the moon, often into madness. In the Landolfi story, the narrator’s friend Y is distraught because his poems (“into which I poured the best of myself,” he says) are stranded in an idiolect that lends itself only to the most brittle translationese. The “great critic” character modeled on Croce fails to reassure the two friends with his view of poetry:

Certainly, an artist is free to put words together before attributing a meaning to them, free even to expect those words, or one single word, to confer meaning and sense to his composition. As long as this is…art. That’s the point. I wouldn’t want you to forget, moreover, that this meaning and sense are certainly not indispensable. A poem, gentlemen, can also make no sense. It must merely, I repeat, be a work of art.

So who’s crazier, the poet or the critic? More confused than ever, the narrator asks the Croce character to explain the “criteria you will employ to make your evaluation,” but instead he escorts his two visitors briskly to the door with an impatient smile and the retort: “Art…everyone knows what art is…”

Like his characters, Landolfi seems both assured and unconvinced of the paradoxical power and instability of the word, of language that always reflects our state of metaphysical uncertainty and striving. “Morto di crepuscolo” (dead of twilight) was his self-epitaph.

Critics complained that Landolfi was too difficult to “comprendere,” but Edoardo Sanguineti retorted that Landolfi was an author “che non sa farsi prendere,” aptly inventing a phrase for this author that, roughly translated, meant that Landolfi’s writing couldn’t be pinned down.

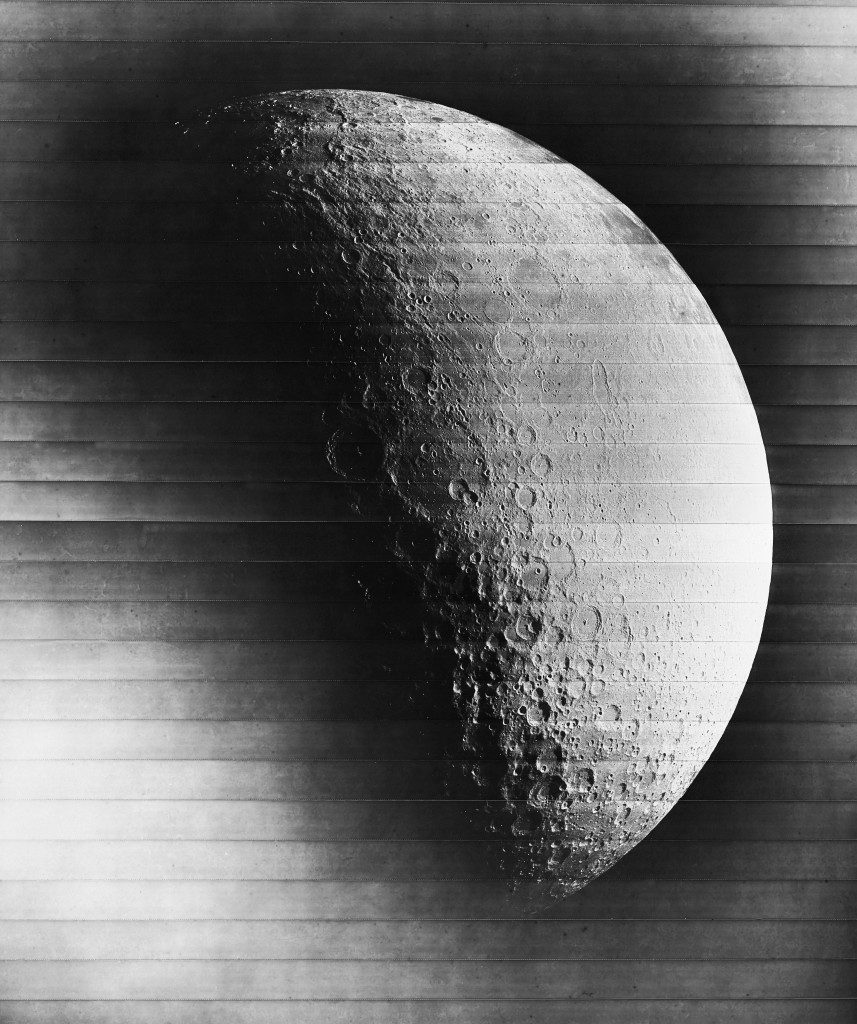

Lunar mist necessarily surrounds Landolfi and his work. Publishing efforts in the States to chart the territory have been sporadic. Words in Commotion (Viking Penguin, 1986) includes a valuable introduction by Italo Calvino. The translation by Kathrine Jason, quoted from above, is excellent.

*

NER Digital is a creative writing series for the web. Nicholas Benson’s translation of Attilio Bertolucci’s Winter Journey (Viaggio d’inverno, 1971) was published in 2005 by Free Verse editions of Parlor Press, and he was awarded a 2008 National Endowment for the Arts Translation Fellowship. He has published translations of poetry by Attilio Bertolucci and Aldo Palazzeschi in NER, and an excerpt from his translation of Scipio Slataper’s novel My Karst (Il mio Carso, 1912) can be found in NER 32:3. The lunar image was created by Michael Benson – see more at the artist’s site, Kinetikon Pictures.